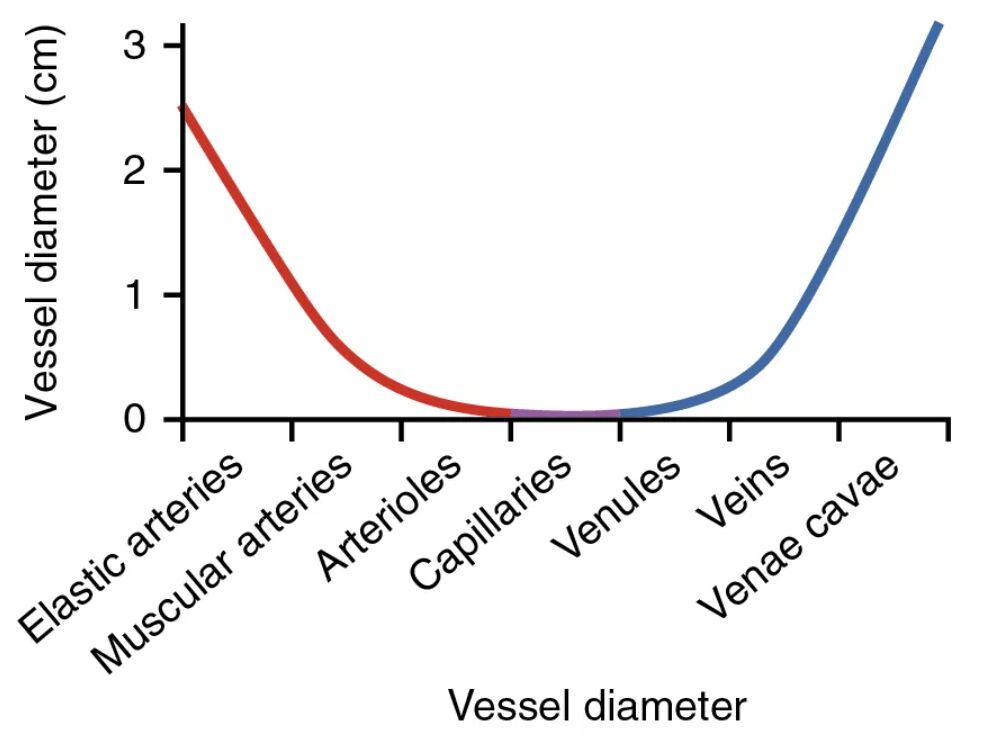

Vessel diameter plays a pivotal role in the circulatory system, influencing blood flow, pressure, and tissue perfusion throughout the body. This diagram provides a detailed look at how the size of blood vessels—ranging from large arteries to tiny capillaries—affects cardiovascular dynamics, offering valuable insights into vascular health.

Aorta Aorta is the largest artery, with a diameter of approximately 2.5-3 cm, serving as the main conduit for oxygenated blood from the heart. Its wide diameter accommodates high-pressure blood flow, distributing it to smaller arteries.

Elastic arteries Elastic arteries, such as the carotid and subclavian arteries, have a diameter of about 1-2 cm and contain elastic fibers to handle pulsatile flow. These vessels smooth out pressure waves, ensuring steady blood delivery to downstream tissues.

Muscular arteries Muscular arteries, like the brachial and femoral arteries, range from 0.5-1 cm in diameter and feature thick muscular walls. They regulate blood flow to specific organs by constricting or dilating, adapting to metabolic demands.

Arterioles Arterioles, with a diameter of 0.01-0.1 cm, act as resistance vessels due to their small size and muscular structure. They control the amount of blood entering capillaries, playing a critical role in blood pressure regulation.

Capillaries Capillaries, the smallest vessels with a diameter of 0.007-0.01 cm, facilitate exchange between blood and tissues. Their tiny size and thin walls allow for efficient diffusion of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products.

Venules Venules, with a diameter of 0.01-0.1 cm, collect blood from capillaries and transition it to larger veins. Their slightly larger size compared to capillaries supports the initial return of deoxygenated blood.

Veins Veins, ranging from 0.5-1 cm in diameter, have thinner walls and serve as capacitance vessels to hold significant blood volume. They rely on valves and muscle action to return blood to the heart against gravity.

Venae cavae Venae cavae, the largest veins with a diameter of about 2-3 cm, carry deoxygenated blood back to the heart. Their wide diameter accommodates low-pressure flow, ensuring efficient venous return.

Overview of Vessel Diameter

This diagram highlights the progressive changes in vessel diameter across the circulatory system. Each segment’s size contributes uniquely to maintaining blood flow and pressure.

- Aorta initiates high-pressure flow with its large diameter.

- Elastic arteries and muscular arteries distribute blood with decreasing diameters.

- Arterioles fine-tune flow with their narrow structure.

- Capillaries enable exchange due to their minimal diameter.

- Venules, veins, and venae cavae facilitate return with increasing sizes.

Anatomical Significance of Vessel Diameter

The variation in vessel diameter reflects specialized functions within the circulatory network. This structural diversity supports the body’s hemodynamic needs.

- Aorta withstands systolic pressure peaks, distributing up to 5 liters of blood per minute.

- Elastic arteries absorb pressure, reducing it to around 100 mmHg by the next level.

- Muscular arteries adjust diameter to direct blood to organs like the liver or kidneys.

- Arterioles reduce flow to 10-20% of arterial volume, controlling capillary entry.

- Capillaries maximize surface area, with thousands per tissue enhancing exchange.

Microcirculation and Capillaries

Capillaries and arterioles form the microcirculation, where diameter critically affects exchange. Their small size is key to physiological processes.

- Arterioles diameter changes regulate blood flow based on oxygen demand.

- Capillaries diameter allows red blood cells to deform, ensuring passage.

- The total cross-sectional area of capillaries exceeds that of arteries, slowing velocity.

- Precapillary sphincters further adjust arterioles diameter for local needs.

- This network supports nutrient delivery and waste removal efficiently.

Venous Return and Larger Vessels

Veins and venae cavae rely on larger diameters for low-pressure return. Their structure aids in accommodating blood volume changes.

- Venules diameter increases as they merge, collecting capillary outflow.

- Veins hold 60-70% of total blood volume due to their compliant walls.

- Venae cavae diameter supports near-zero pressure flow back to the heart.

- Valves within veins prevent backflow despite their wide diameter.

- Muscle pump action enhances return through these larger vessels.

Physical Implications of Vessel Diameter

The diameter of blood vessels influences resistance, flow, and pressure dynamics. These factors are essential for understanding circulatory health.

- Aorta diameter ensures minimal resistance, maintaining high flow velocity.

- Elastic arteries diameter cushions pulsatile flow, reducing shear stress.

- Muscular arteries diameter adjustments affect peripheral resistance.

- Arterioles diameter dictates systemic blood pressure via Poiseuille’s law.

- Capillaries small diameter optimizes diffusion time for oxygen transfer.

Clinical Relevance of Vessel Diameter

Variations in vessel diameter can indicate health conditions or guide treatment. Monitoring these changes supports effective medical care.

- Narrowed arterioles diameter may signal hypertension or atherosclerosis.

- Dilated veins diameter can lead to varicose veins due to valve incompetence.

- Reduced capillaries diameter affects perfusion in diabetes or shock.

- Aorta diameter enlargement suggests aneurysm, requiring surgical evaluation.

- Adjusting muscular arteries diameter with drugs like vasodilators treats angina.

In conclusion, the vessel diameter diagram reveals the critical role of aorta, elastic arteries, muscular arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, veins, and venae cavae in sustaining circulation. This understanding of how diameter influences blood flow, pressure, and exchange deepens appreciation for the circulatory system’s adaptability. It also provides a foundation for addressing vascular challenges with precision and care.