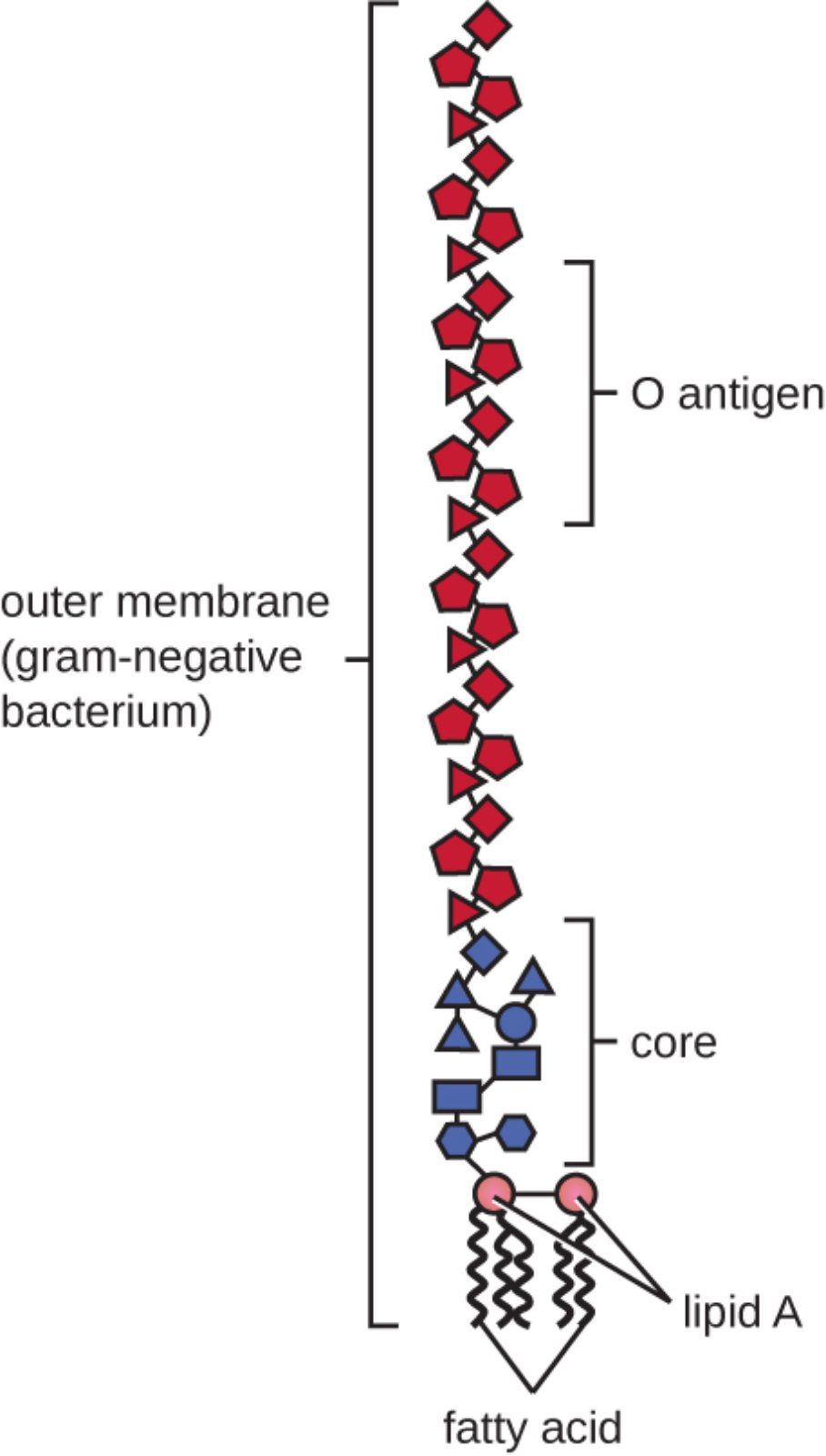

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a complex molecule found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, serving as both a structural component and a powerful endotoxin. Its unique architecture, consisting of Lipid A, a core polysaccharide, and the O antigen, allows these organisms to maintain cellular integrity while triggering intense immune responses in human hosts. By studying this specific molecular arrangement, researchers can better understand the mechanism of Gram-negative bacteria and develop more effective treatments for systemic infections.

outer membrane (gram-negative bacterium): This is the second lipid bilayer that characterizes the surface of Gram-negative organisms, acting as a selective barrier. It is unique in its asymmetric composition, containing lipopolysaccharides on the outer leaflet that provide significant structural protection against the external environment.

O antigen: This is the outermost portion of the LPS molecule, consisting of repeating oligosaccharide units that extend away from the bacterial surface. It is highly variable between different strains and serves as a primary target for the host’s immune system identification and serotyping.

core: The core polysaccharide is the central segment of the LPS molecule that connects the O antigen to the lipid anchor. It usually contains unique sugars such as KDO (2-keto-3-deoxyoctonate) and provides essential stability to the overall molecular structure.

lipid A: This is the hydrophobic anchor of the LPS molecule, embedded directly into the outer membrane of the cell wall. It is medically significant as an endotoxin, capable of triggering systemic inflammation and life-threatening conditions when released into the host’s bloodstream.

fatty acid: These non-polar hydrocarbon chains compose the tail region of Lipid A, ensuring the molecule remains firmly rooted within the lipid environment of the membrane. Their specific chemical arrangement and saturation levels are critical for the biological activity and toxicity of the endotoxin.

The Structural Complexity of the Gram-Negative Envelope

The bacterial outer membrane is a specialized physiological barrier that distinguishes Gram-negative species from other microbial life. Unlike the simple plasma membrane found in Gram-positive cells, this outer layer acts as a sophisticated filter, regulating the entry of nutrients while excluding harmful substances like detergents and certain antibiotics. The primary molecule responsible for these properties is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which provides a negative charge to the cell surface and maintains the structural cohesion of the membrane.

LPS is not a single protein but a large glycolipid complex that covers a significant portion of the cell surface. Its presence is vital for the survival of the bacterium in hostile environments, such as the human digestive tract, where bile salts would otherwise dissolve the cell membrane. The arrangement of the O antigen, core, and Lipid A ensures that the cell remains mechanically stable and chemically resistant.

Key functional features of the LPS structure include:

- Providing a robust permeability barrier against large or hydrophobic molecules.

- Stabilizing the outer membrane through interactions with neighboring LPS molecules and divalent cations.

- Acting as a potent trigger for the host’s innate immune system via pattern recognition receptors.

- Enabling the bacterium to evade phagocytosis by mimicking host sugars or altering its O-antigen length.

From a clinical perspective, the release of these molecules during bacterial growth or cell lysis can have devastating effects on a patient. This transition from a structural component to a mobile toxin is the fundamental cause of several life-threatening medical conditions.

Pathophysiology of Endotoxemia and Septic Shock

When Lipid A enters the systemic circulation, it is recognized by the body’s immune cells—specifically macrophages and neutrophils—through a receptor complex known as TLR4/MD-2. This recognition triggers a massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-alpha and Interleukin-1. While a localized response is helpful for fighting infection, a systemic release of LPS leads to a clinical condition known as Septic shock.

Sepsis is a medical emergency characterized by a dysregulated host response to infection. In cases involving Gram-negative organisms like Escherichia coli or Neisseria meningitidis, the LPS serves as the primary driver of disease. The resulting inflammatory cascade causes widespread vasodilation, leading to a dangerous drop in blood pressure (hypotension). Without immediate medical intervention, this state progresses to multi-organ failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), as the body’s clotting mechanisms become haywire.

Understanding the molecular layout of the outer membrane is essential for developing modern pharmacological interventions. Many current research efforts focus on neutralizing Lipid A or blocking the TLR4 receptor to prevent the cytokine storm associated with endotoxemia. By targeting the very foundation of the Gram-negative bacterial envelope, clinicians hope to reduce the high mortality rates associated with severe sepsis.

The intricate design of lipopolysaccharide represents a perfect balance between microbial defense and physiological impact. While the O antigen and core provide the bacterium with its unique identity and structural strength, Lipid A remains a silent but deadly component of the cell wall. Recognizing the duality of LPS as both a protective shield and a systemic toxin is paramount for advancing our understanding of infectious diseases and improving patient outcomes in critical care settings.