Venography remains a definitive diagnostic and interventional tool in vascular medicine, providing real-time visualization of blood flow dynamics and vessel patency. This article analyzes a comparative set of venograms demonstrating the efficacy of thrombolytic therapy in treating a significant venous occlusion. By examining the transition from a constricted, thrombosed vessel to a fully patent vein, we explore the physiological mechanisms of fibrinolysis and the clinical application of Tissue Plasminogen Activator (tPA).

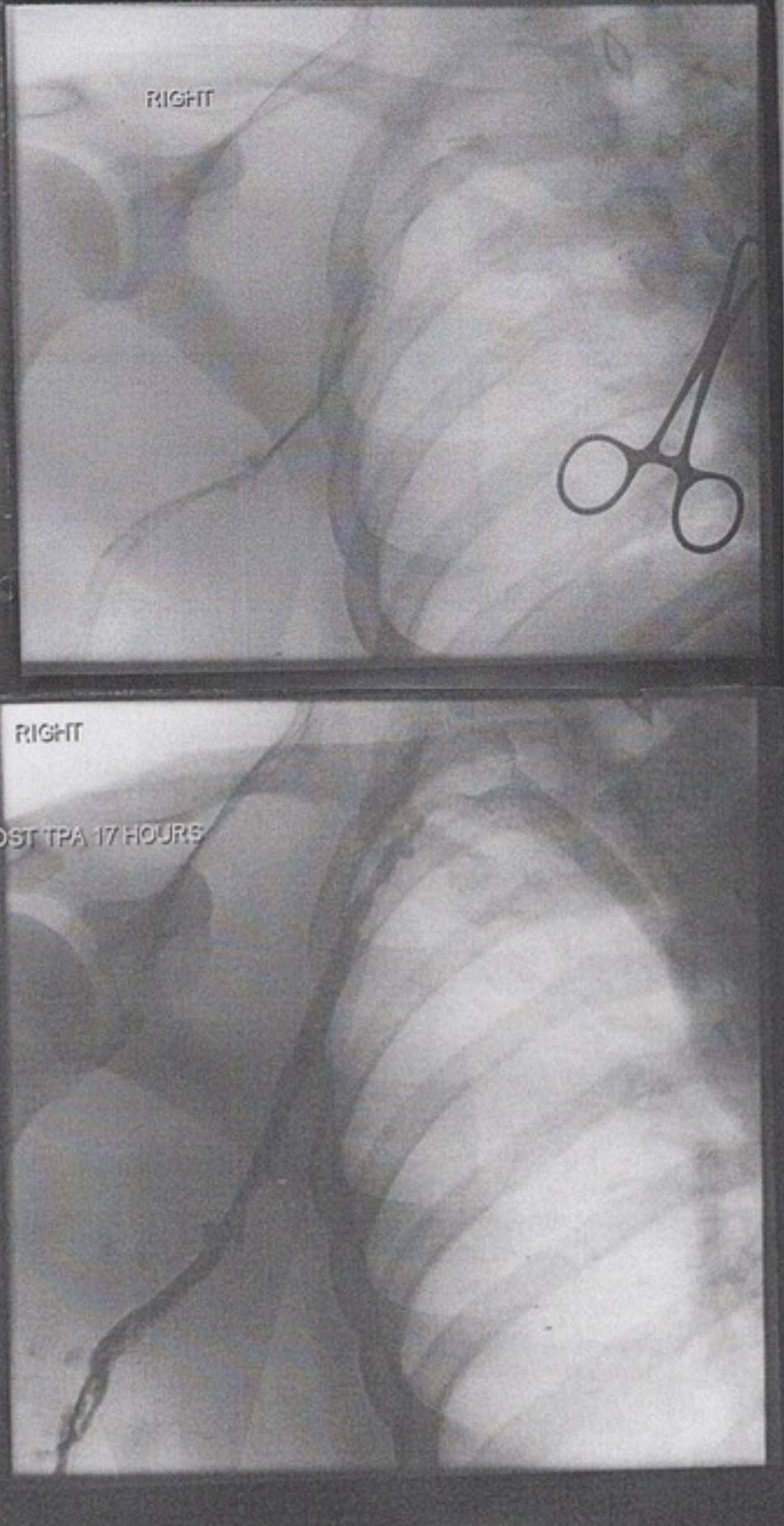

RIGHT: This label indicates the anatomical laterality of the image, confirming that the procedure is being performed on the patient’s right side. In the context of vascular imaging, establishing laterality is a critical safety step to ensure the correct limb or vessel is being treated.

POST TPA 17 HOURS: This annotation marks the timeline of the therapeutic intervention, indicating that the second image was captured 17 hours after the administration of Tissue Plasminogen Activator. It serves as a benchmark to evaluate the effectiveness of the chemical thrombolysis in dissolving the clot over this specific duration.

Introduction to Venography and Thrombolytic Therapy

Venography, also known as phlebography, is an X-ray examination that uses an injection of contrast material to show how blood flows through the veins. While ultrasound is often the first line of defense for diagnosis, contrast venography is frequently used during interventional procedures. The images provided illustrate a classic “before and after” scenario involving a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), likely in the upper extremity (such as the subclavian or axillary vein). The top image reveals the severity of the blockage, while the bottom image highlights the restoration of blood flow.

The primary medical intervention shown here is Thrombolysis, specifically Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis (CDT). Unlike standard anticoagulation therapy (blood thinners), which only prevents a clot from getting larger, thrombolytic agents actively dissolve the clot. The agent mentioned, tPA, is a potent enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, the major enzyme responsible for clot breakdown. This aggressive approach is often reserved for severe cases where the risk of long-term complications, such as post-thrombotic syndrome, is high.

Clinicians typically consider thrombolysis for specific patient presentations. The decision is based on the location of the clot, the severity of symptoms, and the bleeding risk. Common indications for this procedure include:

- Acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis with severe symptoms.

- Upper extremity DVT, often associated with Paget-Schroetter syndrome (effort thrombosis).

- Phlegmasia cerulea dolens, a limb-threatening emergency caused by massive venous obstruction.

- Young patients with a low risk of bleeding who wish to preserve venous valve function.

Pathophysiology of Upper Extremity Deep Vein Thrombosis

The upper image demonstrates a critical interruption in venous return. In a healthy venogram, the contrast dye should fill the vessel lumen completely, appearing as a wide, smooth, dark ribbon on the X-ray. However, the pre-treatment image shows a “string sign” or faint collateral flow. This occurs when a thrombus (blood clot) occupies the majority of the vein’s interior. The clot is composed of aggregated platelets and a mesh of cross-linked fibrin. This obstruction increases hydrostatic pressure behind the clot, forcing blood to find alternative, smaller pathways (collaterals) to return to the heart, which is often visible as a network of thin, spider-web-like vessels.

Upper extremity DVT can be primary, such as in thoracic outlet syndrome where the vein is compressed by the clavicle and first rib, or secondary, often due to central venous catheters or pacemakers. The physiologic consequence is venous hypertension in the arm, leading to swelling, cyanosis (blue discoloration), and pain. If left untreated, the fibrin mesh hardens and organizes, permanently damaging the delicate valves inside the vein and leading to chronic venous insufficiency.

The Mechanism and Result of tPA Administration

The bottom image, labeled “Post TPA 17 Hours,” visually confirms the biochemical success of the treatment. Tissue Plasminogen Activator is a serine protease found on endothelial cells involved in the breakdown of blood clots (fibrinolysis). When administered therapeutically, usually via a catheter placed directly into the clot, it permeates the fibrin mesh. It cleaves the arginine-valine bond in plasminogen to form plasmin. This plasmin then digests the fibrin threads that hold the clot together, effectively liquefying the obstruction.

In the post-treatment venogram, the contrast dye now fills the vein widely and uniformly. The caliber of the vessel appears significantly larger than in the top image, not because the vein has grown, but because the lumen has been recanalized—the obstruction is gone, allowing the contrast to fill the entire space. This restoration of venous return immediately alleviates the back-pressure in the limb, reducing swelling and preventing the long-term sequelae of venous stasis. The clarity of the vessel walls in the second image suggests that the thrombus was relatively fresh, as older, chronic clots are often resistant to chemical lysis.

Conclusion

The comparison between pre-thrombolytic and post-thrombolytic venograms provides compelling evidence for the utility of interventional radiology in managing acute thrombosis. Through the targeted application of tPA, medical teams can reverse significant vascular occlusions, restoring normal hemodynamics and preserving limb function. This visual case study underscores the importance of rapid diagnosis and the effectiveness of fibrinolytic therapy in clearing deep vein obstructions.