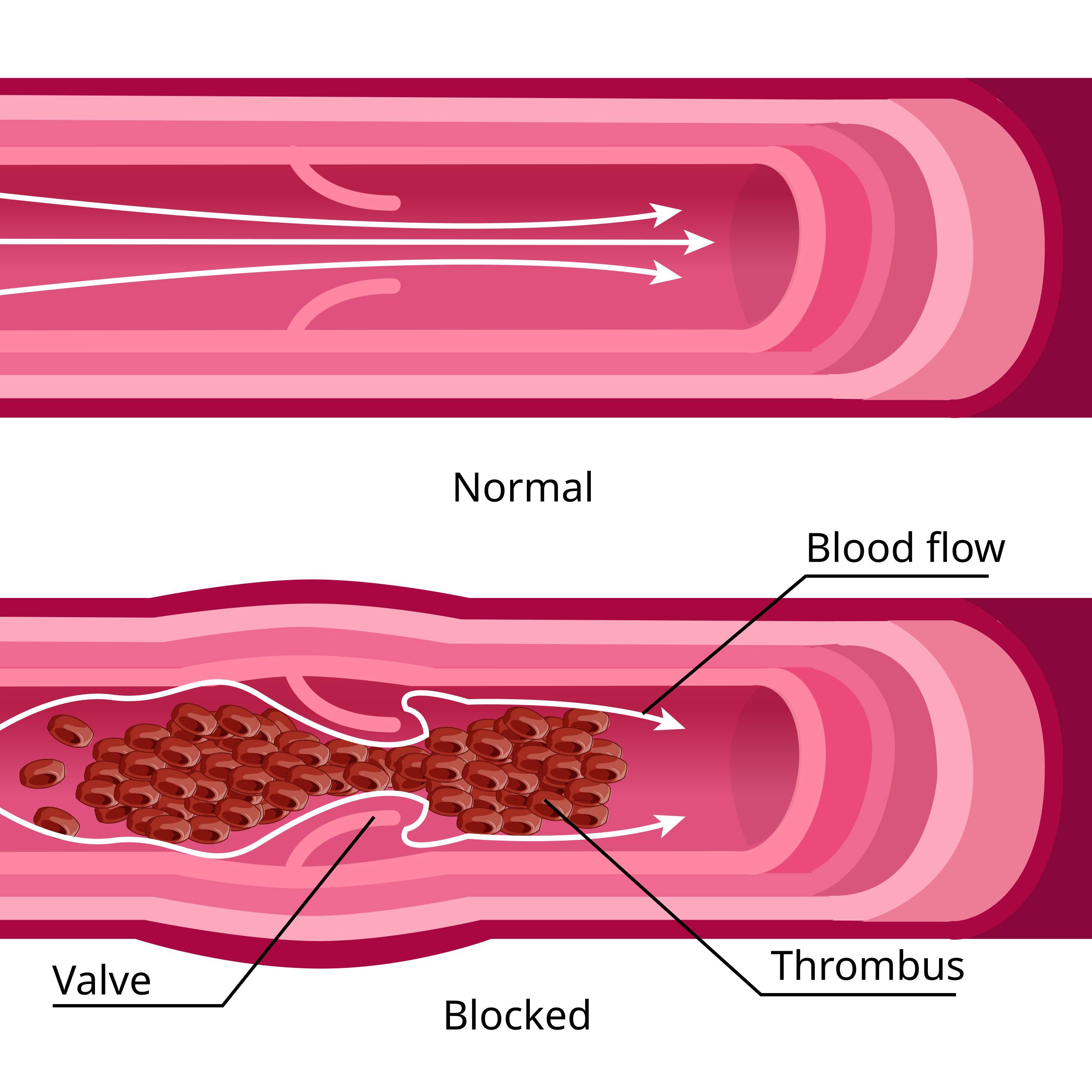

This illustrated guide analyzes the anatomical differences between a healthy vein and one compromised by a thrombus, highlighting the critical role of venous valves in circulation. By examining the mechanics of blood flow obstruction, we explore the physiological causes and dangers of venous thromboembolism as depicted in the comparative diagram.

Normal: This section illustrates a healthy blood vessel, specifically a vein, characterized by smooth, elastic walls and an unobstructed interior lumen. In this state, the vascular system efficiently transports blood back toward the heart without resistance or turbulence.

Blood flow: The white arrows represent the direction and nature of hemodynamic circulation, which is laminar and unidirectional in a healthy vessel. This movement is maintained by the rhythmic contraction of surrounding skeletal muscles and the pressure gradient within the circulatory system.

Valve: These flap-like structures are distinct features of the venous system, designed to prevent the backflow of blood caused by gravity. They open to allow blood to move forward toward the heart and snap shut to prevent regurgitation, ensuring efficient venous return from the extremities.

Blocked: This label highlights the pathological state of the vessel where the lumen is significantly occluded, preventing normal circulation. The walls of the vein may appear distended or inflamed due to the internal pressure caused by the obstruction.

Thrombus: This is the medical term for the blood clot itself, shown here as a dense aggregation of red blood cells, platelets, and fibrin mesh. It has formed specifically around the valve leaflets, creating a physical barrier that disrupts blood flow and poses a risk of detachment.

The Mechanics of Venous Circulation and Stasis

The human circulatory system is comprised of a complex network of vessels, but veins face a unique challenge: they must transport blood against gravity, particularly from the legs back to the heart. Unlike arteries, which rely on the high-pressure pumping of the heart, veins rely on the contraction of skeletal muscles and a system of delicate one-way valves. The image provided offers a clear visual comparison between a functional venous segment and one afflicted by pathology. In the upper “Normal” diagram, the blood flows freely through open valves, illustrating an efficient return system.

However, this system is vulnerable to disruption. The lower “Blocked” diagram represents a failure of hemostasis, leading to the formation of a solid mass within the vessel. This condition typically arises when the delicate balance between clotting factors and blood fluidity is disturbed. The area immediately behind the valve leaflets is a common site for this issue because blood flow can naturally slow down or become turbulent in these pockets, creating an environment conducive to clotting.

Several physiological factors contribute to the transition from the “Normal” state to the “Blocked” state shown in the diagram. Medical professionals often refer to “Virchow’s Triad” to explain why these clots develop. This triad describes three broad categories of factors that contribute to thrombosis:

- Hypercoagulability: An abnormality in the blood chemistry that makes it more prone to clotting, often due to genetics, medication, or cancer.

- Hemodynamic changes (Stasis): Slowing of the blood flow, often caused by immobility, surgery, or long plane rides.

- Endothelial injury: Damage to the inner lining of the vein wall, which can trigger the body’s clotting repair mechanism inappropriately.

Deep Vein Thrombosis: A Silent Danger

The condition depicted in the “Blocked” section of the diagram is clinically known as Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT). This occurs when a thrombus forms in one of the deep veins of the body, most frequently in the lower leg or thigh. The diagram accurately positions the clot around the valve, which is biologically accurate; the pockets behind valve leaflets (valve sinuses) are areas of lower oxygen tension and slower flow, making them the primary starting point for many thrombi. As the clot grows, it incorporates more red blood cells and fibrin, eventually becoming large enough to obstruct the vessel fully or partially.

Symptoms of this condition are directly related to the mechanical blockage shown. When the “Blood flow” is obstructed, blood backs up behind the clot. This leads to increased pressure in the distal veins, causing fluid to leak into the surrounding tissues. Clinically, this presents as swelling (edema), pain, warmth, and redness in the affected leg. However, it is important to note that DVT can sometimes be asymptomatic, making the anatomical understanding of risk factors vital for prevention.

The Role of Venous Valves in Pathology

The venous valves are the heroes of the venous system, but they are also its Achilles’ heel. As seen in the diagram, the thrombus is entangled with the valve structure. Over time, the presence of a clot can permanently damage these delicate leaflets. Even if the body eventually dissolves the clot through natural fibrinolysis or with the help of medication, the valve may remain scarred and incompetent. This leads to a chronic condition known as Post-Thrombotic Syndrome (PTS), where the valve no longer closes properly, causing chronic swelling, skin changes, and venous ulcers.

The most acute danger of the scenario pictured is not just the blockage, but the potential for the thrombus to break loose. If a portion of the clot detaches from the vessel wall or valve, it becomes an embolus. This traveling clot follows the path of blood flow up to the heart and into the lungs, where it can cause a pulmonary embolism (PE). A PE blocks the arteries in the lungs, preventing oxygenation of the blood, which can be fatal. Therefore, the static image of a blocked vessel represents a dynamic and potentially life-threatening medical emergency.

Conclusion

Understanding the anatomy of a blood clot within a vein is essential for recognizing the gravity of venous thromboembolism. The transition from a healthy vessel with laminar flow to a blocked vessel illustrates the mechanical failure that occurs during DVT. By visualizing how thrombi tend to originate around valves and obstruct flow, patients and practitioners can better appreciate the importance of mobility, compression therapy, and anticoagulation in maintaining vascular health and preventing the devastating complications of clot migration.