A lumbar puncture, frequently referred to as a spinal tap, is a fundamental procedure in medical diagnostics used to assess the health of the central nervous system. By inserting a specialized hollow needle into the spinal canal, healthcare providers can harvest cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for laboratory analysis, providing critical data for diagnosing infections, bleeding, and various neurological disorders. This article explores the anatomical basis of the procedure, the physiological importance of patient positioning, and the diagnostic utility of spinal fluid analysis.

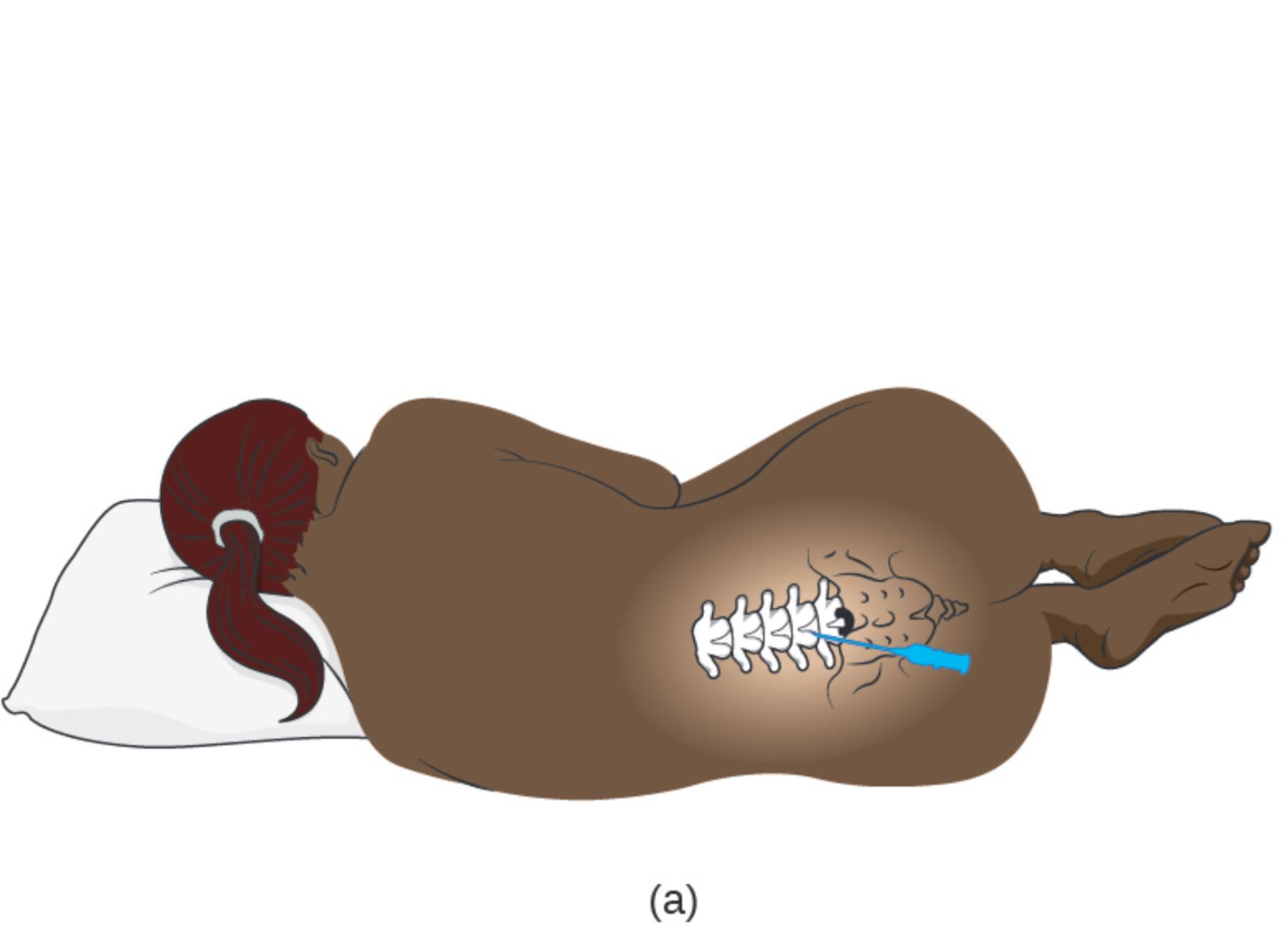

(a): This illustration depicts the standard lateral recumbent position used for an adult lumbar puncture. The patient is positioned on their side with the knees drawn up toward the chest and the neck flexed forward, a posture often described as the “fetal position,” which serves to mechanically widen the spaces between the lumbar vertebrae.

The Importance of Positioning and Anatomy

The success of a lumbar puncture relies heavily on precise surface anatomy and correct patient positioning. As illustrated in the image, the patient is placed in a lateral decubitus (side-lying) position. Crucially, the flexion of the hips and neck stretches the ligaments along the spine. This mechanical action separates the spinous processes of the vertebrae, creating a larger window for the needle to pass through. Without this curvature, the bony structures of the spine would overlap more tightly, making access to the spinal canal difficult and potentially painful.

Anatomically, the procedure is performed in the lower back, specifically between the L3 and L4 or L4 and L5 vertebrae. This location is chosen for a vital safety reason: the solid spinal cord in adults typically terminates at the level of the L1 or L2 vertebra. Below this level, the nerve roots hang loosely in a bundle known as the cauda equina (Latin for “horse’s tail”). By inserting the needle into this lower region, the clinician enters the subarachnoid space to collect fluid without risking damage to the spinal cord itself. The nerve roots in the cauda equina are mobile and simply float away from the advancing needle.

The cerebrospinal fluid collected during this procedure is a clear, colorless liquid that bathes the brain and spinal cord. It acts as a shock absorber, a delivery system for nutrients, and a waste removal mechanism. Because CSF is in direct contact with the central nervous system, its chemical composition changes rapidly in response to disease.

Common indications for performing this procedure include:

- Diagnosing bacterial, viral, or fungal meningitis.

- Detecting subarachnoid hemorrhage (bleeding around the brain).

- Measuring intracranial pressure (opening pressure).

- Diagnosing autoimmune conditions such as Multiple Sclerosis or Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Physiological Mechanics of the Procedure

During the procedure, the needle must pass through several distinct anatomical layers to reach the fluid. After piercing the skin and subcutaneous tissue, the needle traverses the supraspinous ligament, the interspinous ligament, and the ligamentum flavum. The ligamentum flavum is a dense, yellow connective tissue that connects the vertebrae. When the needle penetrates this layer, the physician often feels a distinct “pop,” indicating that the tip has entered the epidural space. Advancing slightly further punctures the dura mater, allowing cerebrospinal fluid to flow out through the needle for collection.

The analysis of the fluid provides a snapshot of the patient’s neurological physiology. In a healthy adult, the fluid contains very few white blood cells and specific levels of glucose and protein. However, if the blood-brain barrier is compromised by infection or inflammation, these values shift. For example, in bacterial infections, the glucose level in the CSF typically drops because bacteria consume the sugar, while protein levels rise.

Conclusion

The adult lumbar puncture is a procedure where precise anatomical knowledge meets clinical necessity. The specific positioning shown in the illustration—knees to chest, spine curved—is not merely for patient comfort but is a physiological requirement to safely open the vertebral spaces. By accessing the subarachnoid space below the termination of the spinal cord, medical professionals can safely obtain the biological information needed to diagnose life-threatening conditions and guide effective treatment plans.