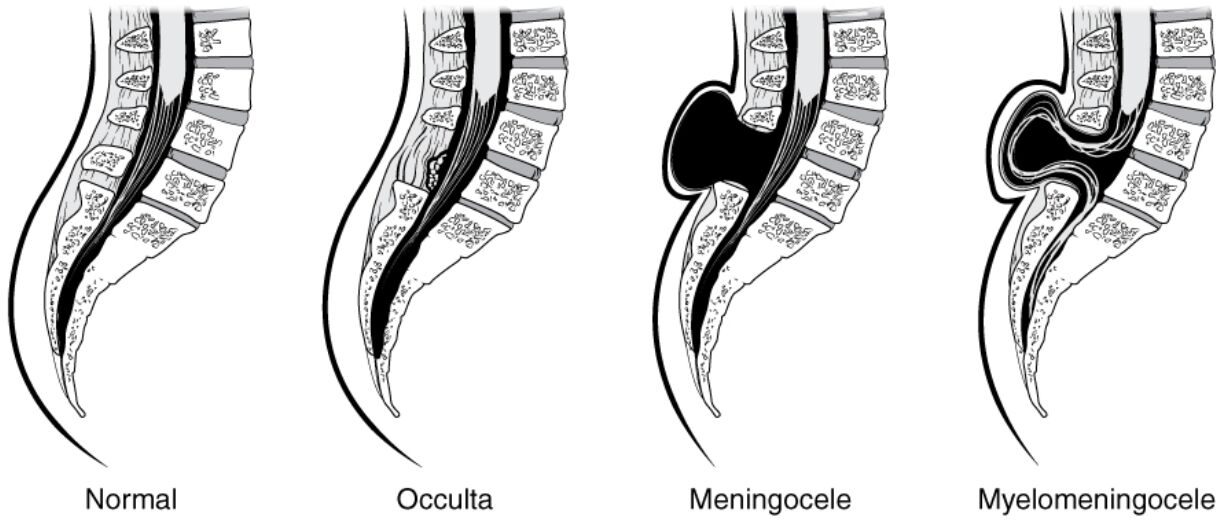

Spina bifida is a congenital condition affecting the spinal cord, resulting from the incomplete closure of the neural tube during early development. This diagram illustrates the four main types of spina bifida, providing a visual comparison of normal spinal structure and the varying degrees of malformation. Exploring these illustrations helps in recognizing the anatomical changes and their implications for those affected by this condition.

Normal: The normal spinal structure shows a fully closed neural tube with the spinal cord encased within intact vertebrae, ensuring proper nerve function. This configuration supports the spinal cord’s protection and allows for normal movement and sensation.

Occulta: Occulta is the mildest form of spina bifida, where the spinal cord remains intact, but there is a small gap or defect in one or more vertebrae, often with minimal symptoms. It may go undiagnosed unless detected through imaging, as it typically does not involve protrusion of tissues.

Meningocele: Meningocele occurs when the meninges, the protective layers around the spinal cord, push through an opening in the vertebrae, forming a sac filled with cerebrospinal fluid. This condition may cause neurological issues depending on the size and location of the sac, often requiring surgical intervention.

Myelomeningocele: Myelomeningocele is the most severe form, where both the meninges and a portion of the spinal cord protrude through the vertebral defect, leading to significant nerve damage. This type often results in paralysis, bladder dysfunction, and other complications, necessitating comprehensive medical care.

Overview of Spina Bifida Types

Spina bifida manifests as a spectrum of neural tube defects, each with distinct anatomical features. These illustrations provide a clear depiction of how the condition alters the spinal column.

- The Normal spine serves as a baseline, with a fully formed vertebral arch protecting the spinal cord.

- Occulta presents a subtle defect, often covered by skin, making it less apparent at birth.

- Meningocele involves a visible sac, which can vary in size and impact surrounding nerves.

- Myelomeningocele exposes the spinal cord, leading to more pronounced neurological deficits.

Early diagnosis through imaging like ultrasound or MRI is crucial for managing these conditions effectively.

Anatomical and Clinical Implications

The diagrams highlight the progressive severity of spina bifida, offering insights into its anatomical and clinical effects. Each type presents unique challenges that influence treatment approaches.

- The Normal spinal cord’s integrity ensures unobstructed nerve signal transmission to the body.

- Occulta’s minor defect may be asymptomatic, but it can sometimes be associated with tethered cord syndrome over time.

- Meningocele’s fluid-filled sac can compress nerves, potentially causing pain or weakness if untreated.

- Myelomeningocele’s exposure of the spinal cord often leads to hydrocephalus, requiring shunt placement for cerebrospinal fluid management.

Surgical correction and physical therapy are common interventions, tailored to the severity of the defect.

Causes and Risk Factors

The development of spina bifida is influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Understanding these can aid in prevention and early intervention.

- Folic acid deficiency during pregnancy is a major risk factor, emphasizing the need for supplementation.

- Genetic predisposition may increase susceptibility, particularly in families with a history of neural tube defects.

- Environmental factors, such as maternal diabetes or obesity, can contribute to the condition’s likelihood.

- Prenatal screening, including alpha-fetoprotein levels, helps identify at-risk pregnancies for timely management.

Preventive measures like adequate folic acid intake can significantly reduce the incidence of spina bifida.

Treatment and Management

Managing spina bifida requires a multidisciplinary approach, depending on the type and severity. Long-term care focuses on improving quality of life.

- Occulta may not require treatment unless symptoms like pain or neurological changes emerge.

- Meningocele often involves surgery to repair the sac and prevent infection or nerve damage.

- Myelomeningocele necessitates immediate surgery to protect the spinal cord, followed by ongoing therapy.

- Rehabilitation, including physical and occupational therapy, addresses mobility and independence challenges.

Regular follow-ups with specialists ensure optimal outcomes for affected individuals.

Conclusion

This diagram of the four types of spina bifida—Normal, Occulta, Meningocele, and Myelomeningocele—offers a comprehensive visual guide to understanding this congenital defect. By illustrating the progression from a healthy spine to severe malformations, it underscores the importance of early detection and tailored treatment. This knowledge equips individuals with the insights needed to address the challenges posed by spina bifida effectively.