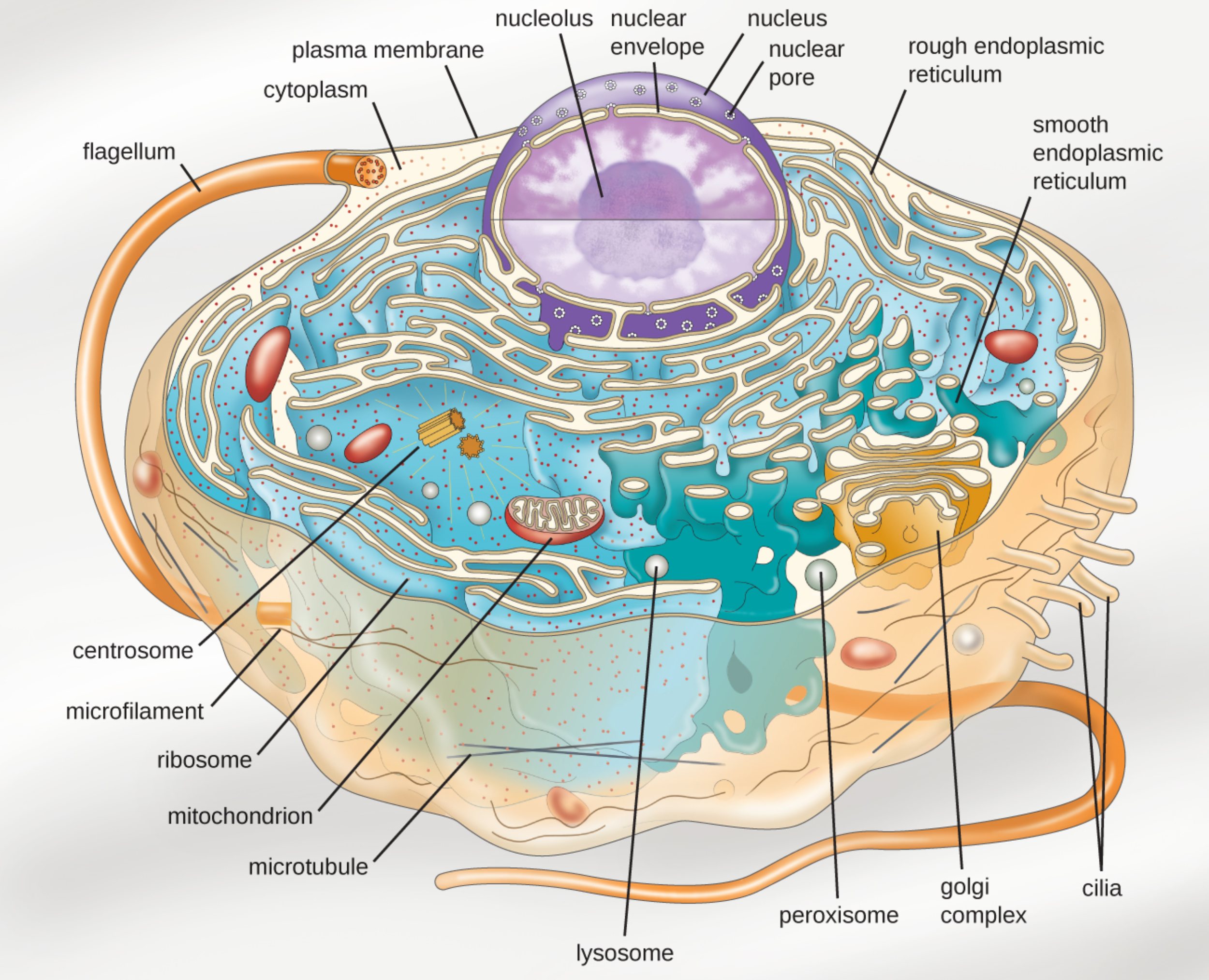

A generalized eukaryotic cell represents a highly organized biological system containing specialized organelles that perform essential life functions. From the genetic command center of the nucleus to the energy-producing mitochondria, each component is vital for maintaining homeostasis and supporting the organism’s survival through complex biochemical processes.

Flagellum: This whip-like appendage extends from the cell body and facilitates locomotion through liquid environments. It utilizes a specialized arrangement of microtubules that slide against one another to create a rhythmic, propeller-like motion.

Plasma membrane: This semi-permeable phospholipid bilayer acts as the boundary of the cell, regulating the entry and exit of molecules. It is essential for protecting the internal environment and facilitating communication via various surface receptors and transport proteins.

Cytoplasm: This gel-like substance fills the interior of the cell and serves as the medium for all internal organelles. It provides the necessary environment for metabolic reactions and helps maintain the cell’s overall volume and shape.

Nucleolus: Located deep within the nucleus, this dense region is the primary site for the synthesis and assembly of ribosomal subunits. It is crucial for the production of the machinery required for subsequent protein synthesis in the cytoplasm.

Nuclear envelope: This double-membrane structure encloses the genetic material, providing a distinct boundary between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. It helps protect DNA from chemical reactions occurring in other parts of the cell while managing molecular traffic.

Nucleus: Often described as the brain of the cell, the nucleus contains the vast majority of the organism’s genetic information. It coordinates vital activities such as growth, metabolism, and cell division by regulating gene expression.

Nuclear pore: These large protein complexes span the nuclear envelope and act as highly selective gateways. They control the transport of RNA and proteins into and out of the nucleus to ensure genetic instructions are accurately followed.

Rough endoplasmic reticulum: This network of membranes is studded with ribosomes, giving it a distinctively granulated appearance. Its primary role involves the synthesis, folding, and modification of proteins that are destined for secretion or membrane integration.

Smooth endoplasmic reticulum: Lacking ribosomes on its surface, this organelle is primarily responsible for lipid synthesis and the detoxification of metabolic byproducts. It also plays a significant role in sequestering calcium ions, which are vital for intracellular signaling.

Cilia: These short, hair-like projections move in a coordinated wave-like pattern to either propel the cell or move substances across its surface. They are frequently found on the surface of specialized cells, such as those lining the respiratory tract in higher organisms.

Golgi complex: Often referred to as the shipping and receiving center, this organelle processes and packages proteins and lipids into vesicles. It modifies molecules received from the endoplasmic reticulum before directing them to their final cellular or extracellular destinations.

Peroxisome: These small, membrane-bound organelles contain oxidative enzymes that break down fatty acids and amino acids. They play a critical role in neutralizing toxic substances like hydrogen peroxide, preventing oxidative damage to the cell.

Lysosome: Serving as the cell’s primary digestive system, lysosomes contain acidic hydrolases that break down waste materials and cellular debris. They are essential for recycling old organelles and defending the cell against invading pathogens through phagocytosis.

Microtubule: These hollow protein tubes are a core component of the cytoskeleton, providing structural support and acting as “tracks” for intracellular transport. They are also indispensable during cell division, where they form the mitotic spindle to separate chromosomes.

Mitochondrion: Known as the powerhouse of the cell, this organelle is the site of cellular respiration, where nutrients are converted into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). They possess their own unique DNA and are thought to have originated from an ancient symbiotic relationship.

Ribosome: These small structures are the sites of translation, where genetic messages are turned into functional polypeptide chains. They can be found floating freely in the cytosol or attached to the rough endoplasmic reticulum depending on the protein’s destination.

Microfilament: Composed mainly of actin, these thin protein fibers provide mechanical strength and are involved in various types of cellular movement. They are essential for maintaining cell shape and facilitating the contraction of muscle cells.

Centrosome: This region serves as the main microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) in animal cells. It typically contains a pair of centrioles and is vital for organizing the microtubule network during the process of mitosis.

The Architecture of Eukaryotic Life

The complexity of eukaryotic organisms is defined by their compartmentalized nature, which separates diverse chemical reactions into specific membrane-bound areas. Unlike simpler prokaryotic cells, eukaryotes possess a high degree of internal organization that allows for more sophisticated metabolic pathways. This division of labor ensures that processes like DNA replication and protein synthesis can occur simultaneously without interference, maximizing cellular efficiency.

The cytoskeleton provides the necessary internal framework that holds these various organelles in place while allowing for dynamic movement. Composed of microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments, this network is not a static skeleton but a constantly shifting structure. It responds to environmental signals, allowing the cell to change shape, migrate toward nutrients, or divide into daughter cells during reproduction.

In a medical context, understanding these cellular structures is fundamental to diagnosing and treating a wide range of human conditions. Many genetic disorders are localized to specific organelles, such as mitochondrial diseases that impair energy production or lysosomal storage diseases that lead to the toxic accumulation of cellular waste. By focusing on the molecular mechanics of these structures, researchers can develop targeted gene therapies and pharmaceutical interventions.

Key characteristics of eukaryotic cellular organization include:

- A membrane-bound nucleus that protects the organism’s genomic integrity.

- Highly specialized organelles for energy production, protein synthesis, and waste management.

- A dynamic endomembrane system for the transport of molecules.

- The presence of a complex cytoskeleton for structural support and mobility.

Cellular Physiology and Genetic Coordination

The physiological harmony of a cell depends on the precise execution of the genetic code housed within the nucleus. DNA serves as the master blueprint, dictating every aspect of the cell’s function through the production of enzymes and structural proteins. Through the processes of transcription and translation, the cell converts silent genetic instructions into the active machinery of life, ensuring that the organism can respond to external stressors and maintain its internal balance.

Energy dynamics are equally critical to cellular survival. Mitochondria facilitate the conversion of chemical energy from food into a usable form via oxidative phosphorylation. This process requires a steady supply of oxygen and glucose, which is why cellular respiration is so central to aerobic life. When mitochondrial function is compromised, tissues with high energy demands, such as the heart and brain, are often the first to suffer from significant physiological decline.

Furthermore, the cell’s ability to detoxify itself and recycle materials is what allows for long-term viability. The coordination between peroxisomes, which handle oxidative stress, and lysosomes, which manage molecular degradation, prevents the buildup of cellular “garbage” that could otherwise lead to premature cell death or oncogenic transformations. This internal maintenance system is a hallmark of the sophisticated evolutionary path taken by eukaryotic organisms.

The intricate coordination of these cellular parts highlights the elegance of biological systems. Every organelle, from the smallest ribosome to the massive nucleus, contributes to the overall health and function of the organism. As medical science continues to advance, our ability to manipulate these cellular pathways offers hope for curing diseases once thought to be insurmountable, reinforcing the vital importance of basic cellular anatomy and physiology.