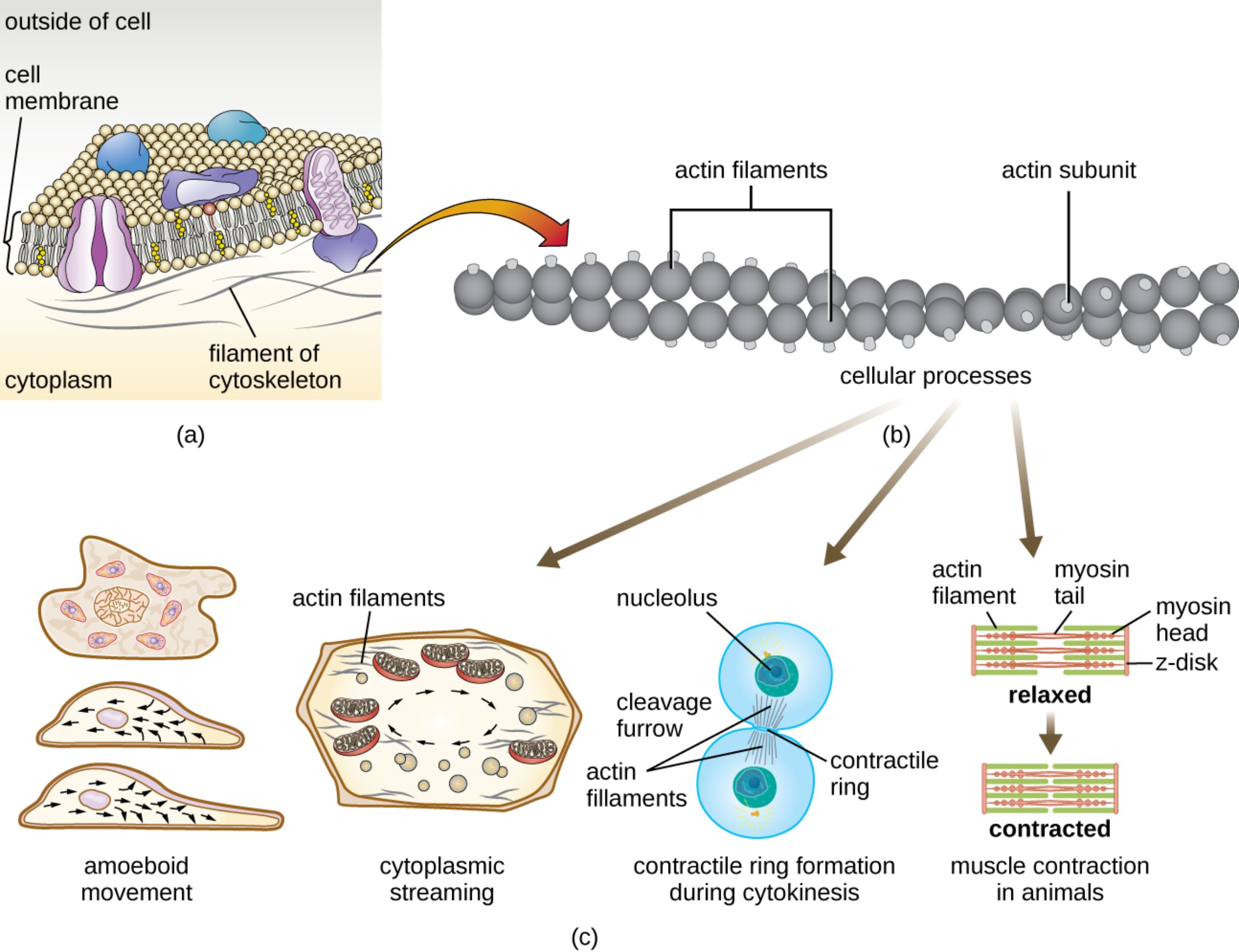

Actin microfilaments are indispensable protein structures that drive essential cellular processes, from intracellular transport to the complex mechanics of human muscle movement. By understanding the dynamic polymerization of actin subunits, we can better appreciate the physiological basis of how our bodies function at a microscopic level. This comprehensive guide explores the structural assembly of microfilaments and their diverse roles in maintaining cellular health and motility.

outside of cell: This region represents the extracellular environment where signaling molecules and nutrients interact with the cell’s surface. It serves as the external matrix that cells must often navigate or respond to through membrane-bound receptors.

cell membrane: This semi-permeable phospholipid bilayer acts as a protective boundary for the cell, regulating the passage of ions and molecules. It provides a structural anchor for the underlying cytoskeleton, allowing the cell to maintain its shape or change it during movement.

cytoplasm: This is the viscous, gel-like substance that fills the interior of the cell and houses various organelles. It serves as the medium through which actin filaments traverse to facilitate internal transport and structural support.

filament of cytoskeleton: These are the protein-based fibers that form a complex network throughout the cytoplasm to provide mechanical stability. In this context, they specifically refer to the microfilaments that lie just beneath the cell membrane to assist in structural integrity.

actin filaments: These structures consist of two intertwined strands of polymerized protein monomers that form the fundamental microfilament unit. They are highly dynamic, constantly assembling and disassembling to allow the cell to adapt to various physiological needs.

actin subunit: These are individual globular protein molecules, known as G-actin, which link together to form long, helical filaments. The energy-dependent addition of these subunits at the “plus end” of a filament is what drives cellular expansion and movement.

cellular processes: This term encompasses the wide array of biological activities that rely on the structural and motor capabilities of the cytoskeleton. These include everything from nutrient distribution and cell division to the macroscopic contraction of muscles.

amoeboid movement: This type of locomotion involves the extension of the cell membrane into temporary, foot-like projections used for crawling. This process is driven by the rapid polymerization of actin at the leading edge, allowing cells like macrophages to navigate through tissues.

cytoplasmic streaming: This is the circular flow of cytoplasm within the cell that helps distribute nutrients, enzymes, and organelles efficiently. This “stirring” motion is powered by the interaction between actin filaments and myosin motor proteins.

nucleolus: Located within the nucleus, this dense structure is primarily responsible for the synthesis of ribosomal RNA. During the late stages of the cell cycle, it remains protected while the surrounding cytoplasm undergoes division.

cleavage furrow: This is the visible indentation that forms on the cell surface during the final stages of cell division. It marks the precise location where the cell will eventually split into two distinct daughter cells.

contractile ring: Composed of actin and myosin, this structure forms just beneath the plasma membrane at the cleavage furrow to facilitate cytokinesis. It functions similarly to a drawstring, tightening until the parent cell is physically pinched into two.

actin filament (muscle context): In muscle tissue, these are thin filaments that slide alongside thicker filaments to generate force. They are meticulously organized into repeating units to ensure that contraction occurs simultaneously across the entire fiber.

myosin tail: This is the elongated portion of the myosin protein that bundles with other tails to form the central core of the thick filament. It provides the structural stability required for the myosin heads to exert mechanical leverage.

myosin head: These are the globular regions of the myosin molecule that bind to actin and hydrolyze adenosine triphosphate to produce motion. During a contraction, these heads perform a “power stroke” that pulls the actin filaments inward.

z-disk: This protein-rich structure serves as the anchor point for actin filaments within the muscle fiber. It defines the boundaries of a sarcomere, which is the basic functional unit of muscle contraction.

relaxed: This term describes the state of a muscle fiber when actin and myosin filaments have minimal overlap and are not exerting force. In this phase, the sarcomeres are extended, and the muscle is at its resting length.

contracted: In this state, the interaction between actin and myosin has pulled the z-disks closer together, shortening the sarcomere. This microscopic shortening across millions of units results in the physical contraction of the entire muscle.

muscle contraction in animals: This is the complex physiological process that converts chemical energy into mechanical work through the sliding filament mechanism. It is essential for every movement, from the beating of the heart to the lifting of heavy objects.

The Foundation of Cellular Motility and Structure

The cytoskeleton is a dynamic framework of protein filaments that provides eukaryotic cells with their shape, strength, and ability to move. Among the three main types of cytoskeletal fibers, microfilaments—composed primarily of the protein actin—are the thinnest and most versatile. These fibers are not permanent fixtures but are instead in a constant state of flux, growing and shrinking to meet the metabolic and structural demands of the cell. This adaptability is key to the cell’s ability to respond to its environment.

When actin subunits polymerize into filaments, they create a scaffold that can resist tension and provide a platform for motor proteins. The interaction between actin and its primary motor partner, myosin, is what transforms a static structural fiber into a source of mechanical force. This relationship is fundamental to life, appearing in various forms across different cell types and species.

The dynamic nature of actin allows for several critical cellular functions, including:

- The formation of pseudopodia for cell crawling and engulfing foreign particles.

- The distribution of intracellular materials through cytoplasmic streaming.

- The physical separation of cells during the division process.

- The generation of force in both skeletal and cardiac muscle tissues.

In a medical context, the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton is vital for preventing diseases related to cell migration, such as cancer metastasis. When the control mechanisms for actin polymerization fail, cells may become hyper-mobile or lose their structural integrity, leading to pathological states. Understanding these pathways is essential for developing targeted therapies that can modulate cellular behavior at the molecular level.

Physiological Mechanisms of Muscle and Movement

The most well-known application of actin-myosin interaction is in the skeletal muscle system. Within a muscle fiber, actin and myosin are arranged into highly ordered structures called sarcomeres. When a nerve impulse triggers the release of calcium ions, the binding sites on the actin filaments are exposed, allowing the myosin heads to attach. This initiates the sliding filament theory, where the filaments slide past each other without changing their individual lengths, thereby shortening the sarcomere and the muscle as a whole.

Beyond muscle, actin plays a crucial role in non-muscle cells through ameboid movement. This process is essential for the human immune system, as it allows white blood cells to squeeze through the walls of blood vessels and migrate toward sites of infection or injury. By extending the cell membrane forward and then pulling the rest of the cell body along, these cells can effectively “patrol” the body for pathogens.

Furthermore, during the final stage of cell division, the formation of a contractile ring ensures that genetic material is properly partitioned. The ring, made of actin and myosin, pinches the cell membrane inward until two separate cells are formed. Any disruption in this process can lead to multinucleated cells or chromosomal instability, highlighting the importance of actin in maintaining genetic health throughout a person’s life.

The multifaceted nature of actin highlights the elegance of biological design, where a single protein type can facilitate such diverse functions. Whether it is a white blood cell chasing a pathogen or a bicep muscle lifting a heavy weight, the underlying mechanics remain consistent. By continuing to explore the intricate dance between actin and myosin, researchers can unlock new treatments for muscular dystrophies and other motility-related disorders, ensuring the health and vitality of the human body.