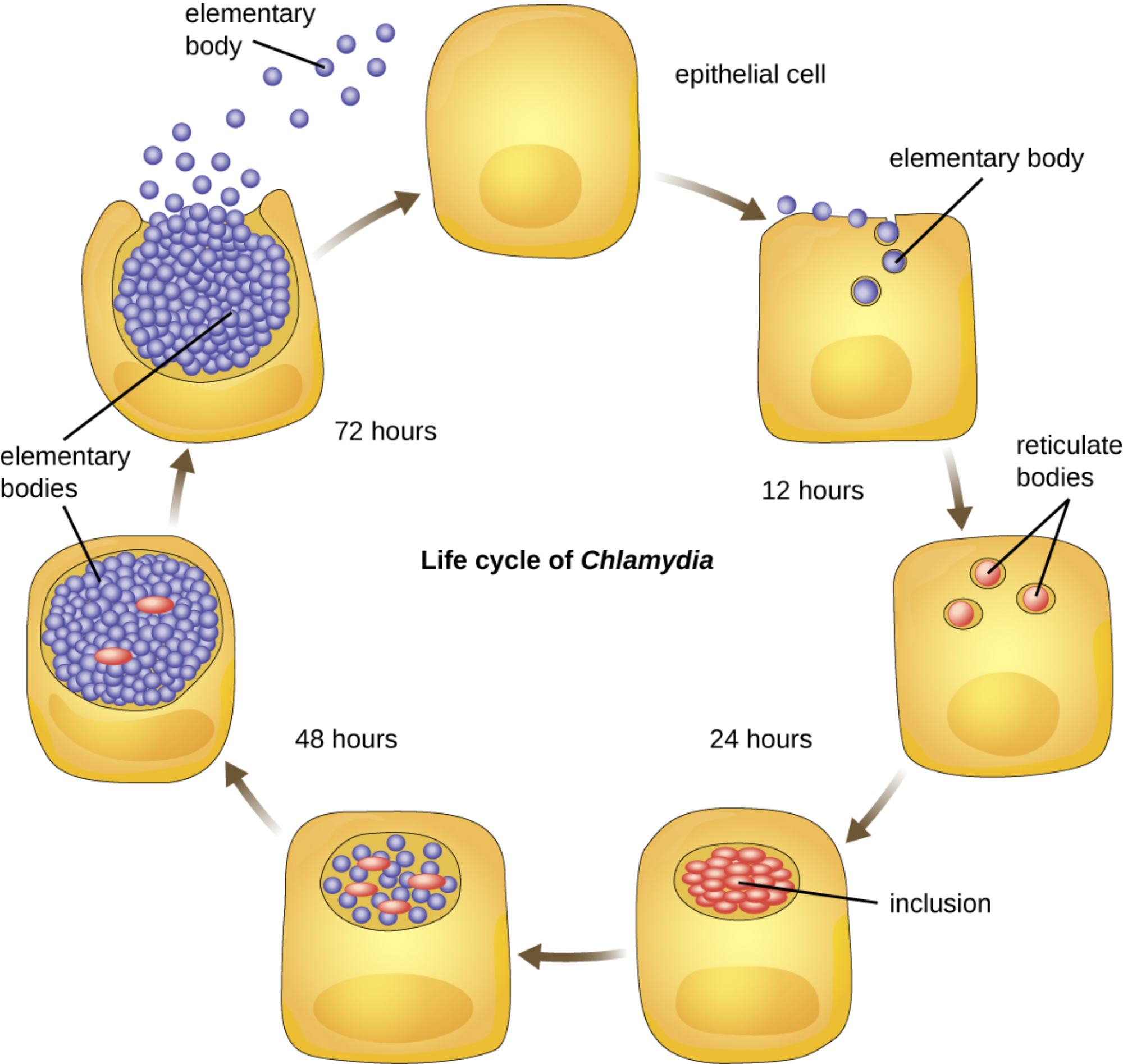

The life cycle of Chlamydia is a complex, biphasic process involving distinct infectious and reproductive stages. By targeting epithelial cells and depleting host energy reserves, this obligate intracellular pathogen effectively replicates and spreads, often resulting in significant reproductive health complications if left untreated.

elementary body: This is the infectious, metabolically inactive form of the bacterium designed to survive in the extracellular environment. It acts like a spore, attaching to the surface of a healthy host cell to initiate the entry process.

epithelial cell: These are the primary host cells targeted by Chlamydia species during an infection, typically found in the lining of the reproductive or urinary tracts. These cells provide the sheltered environment and metabolic resources necessary for the bacteria to thrive and replicate.

reticulate bodies: Once the infectious particles enter the cell, they transform into this larger, metabolically active form. Reticulate bodies focus entirely on reproduction, utilizing the host cell’s resources to multiply through binary fission.

inclusion: This is a specialized, membrane-bound vacuole created by the bacteria within the host cell’s cytoplasm. The inclusion acts as a protective “nursery,” shielding the replicating reticulate bodies from the host’s lysosomal enzymes and immune detection.

elementary bodies: At the conclusion of the 72-hour cycle, the reticulate bodies reorganize back into these infectious particles. Upon the death and rupture of the host cell, hundreds of these new bodies are released to find and infect neighboring healthy cells.

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most prevalent bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) worldwide, characterized by its unique survival strategy as an obligate intracellular pathogen. Unlike many other bacteria, Chlamydia cannot produce its own energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and must “steal” it from the host. This dependency makes the pathogen exceptionally difficult to study in standard laboratory cultures, as it requires living host cells for growth.

The infection is notoriously difficult to diagnose based on symptoms alone because it is frequently asymptomatic, earning it the nickname “the silent infection.” When symptoms do occur, they may include abnormal discharge, dysuria, or pelvic pain. However, even without symptoms, the bacteria can cause significant damage to the reproductive system, leading to long-term health consequences for both men and women.

Key milestones in the Chlamydia developmental cycle:

- 0–12 Hours: Elementary bodies attach to the host cell and are internalized into an inclusion, where they transform into reticulate bodies.

- 12–24 Hours: The reticulate bodies begin rapid multiplication through binary fission, significantly expanding the inclusion.

- 24–48 Hours: The inclusion continues to grow as reticulate bodies utilize host ATP, eventually beginning their transition back into infectious elementary bodies.

- 72 Hours: The host cell, depleted of nutrients and energy, ruptures or undergoes programmed cell death, releasing the new generation of infectious particles.

Pathogenesis and Clinical Impact of Chlamydial Infection

The clinical significance of Chlamydia lies in its ability to cause chronic inflammation. In women, untreated infections can ascend from the cervix to the upper reproductive tract, leading to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). This condition can cause permanent scarring of the fallopian tubes, which is a leading cause of ectopic pregnancies and tubal factor infertility. In men, the infection can cause epididymitis, which may lead to pain and potential fertility issues if left unmanaged.

Because Chlamydia exists in two distinct forms, its interaction with the immune system is unique. While the elementary bodies are susceptible to neutralizing antibodies when they are outside the cell, the reticulate bodies remain hidden within the protective inclusion. The bacteria also employ various “stealth” mechanisms to prevent the host cell from triggering an early immune response, allowing the 72-hour replication cycle to complete successfully before the cell finally dies.

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Public Health

Modern medicine relies on high-sensitivity testing to identify these infections. The gold standard for diagnosis is the NAAT (Nucleic Acid Amplification Test), which can detect even small amounts of chlamydial DNA in urine or swab samples. This technology has revolutionized screening programs, allowing for faster and more accurate detection than traditional cell culture methods.

Treatment for Chlamydia is generally highly effective if the infection is caught early. Because the bacteria lack a traditional peptidoglycan cell wall, they are resistant to many common antibiotics like penicillin. Instead, clinicians typically prescribe macrolides or tetracyclines, which target the bacteria’s protein synthesis. It is vital for all sexual partners to be treated simultaneously to prevent “ping-pong” reinfections and to ensure the localized outbreak is completely eradicated.

Understanding the microscopic life cycle of Chlamydia provides the foundation for better diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. By disrupting the transition between elementary and reticulate bodies, researchers hope to develop new ways to prevent this pathogen from establishing the chronic infections that threaten reproductive health globally. Through regular screening and prompt treatment, the most severe complications of this intracellular parasite can be effectively avoided.