Understanding the Autonomic Efferent Pathway: A Comprehensive Guide to Neural Transmission in the Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic efferent pathway plays a crucial role in regulating involuntary bodily functions, such as heart rate, digestion, and glandular secretions, by transmitting signals from the central nervous system to peripheral target organs. This pathway involves a two-neuron chain that ensures precise control over smooth muscles, cardiac muscles, and glands, distinguishing it from the somatic nervous system which directly innervates skeletal muscles. Through myelinated and unmyelinated axons, the autonomic system maintains homeostasis without conscious effort, highlighting its importance in everyday physiological processes.

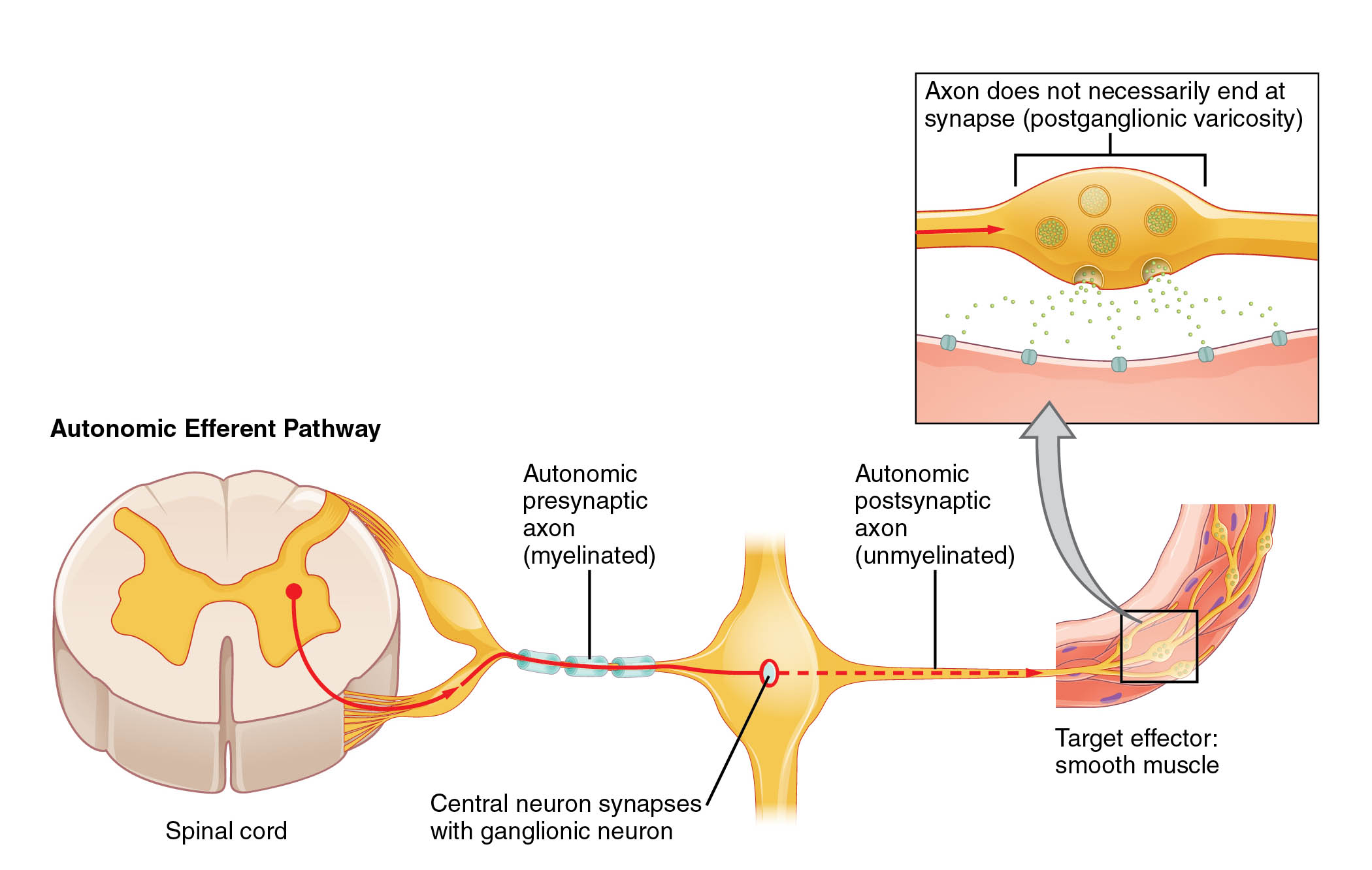

Key Labeled Components in the Diagram

Spinal cord The spinal cord serves as the origin point for many autonomic efferent signals, acting as a conduit between the brain and peripheral nerves. It houses preganglionic neurons that extend outward to form synapses with postganglionic neurons in autonomic ganglia.

Autonomic presynaptic axon (myelinated) The autonomic presynaptic axon, also known as the preganglionic axon, is myelinated to facilitate rapid signal transmission from the central nervous system. This myelination allows for efficient conduction of action potentials over longer distances before reaching the ganglion.

Central neuron synapses with ganglionic neuron This label refers to the synaptic junction where the central preganglionic neuron communicates with the peripheral postganglionic neuron within an autonomic ganglion. Neurotransmitters like acetylcholine are released here to propagate the signal, ensuring coordinated autonomic responses.

Autonomic postsynaptic axon (unmyelinated) The autonomic postsynaptic axon, or postganglionic axon, lacks myelin, resulting in slower conduction speeds suited for diffuse innervation of target tissues. This unmyelinated structure enables the axon to branch extensively and release neurotransmitters along its length.

Target effector: smooth muscle Smooth muscle represents a primary target for autonomic efferent signals, contracting or relaxing in response to neural input to control functions like blood vessel diameter or gut motility. Unlike skeletal muscle, it operates involuntarily and can sustain contractions without fatigue.

Axon does not necessarily end at synapse (postganglionic varicosity) Postganglionic varicosities are swellings along the axon that release neurotransmitters into the extracellular space rather than at a traditional synapse. This en passant release allows for widespread influence on effector cells, enhancing the modulatory effects of the autonomic nervous system.

Overview of the Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is divided into sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions, each with distinct efferent pathways that originate from different regions of the central nervous system. These pathways ensure balanced regulation of internal organs, adapting to stressors or rest states seamlessly.

- The sympathetic division typically prepares the body for “fight or flight” responses, increasing heart rate and redirecting blood flow.

- In contrast, the parasympathetic division promotes “rest and digest” activities, such as enhancing salivary secretion and slowing heartbeat.

- Both divisions utilize the two-neuron efferent pathway depicted in the diagram, starting from the spinal cord or brainstem.

- Preganglionic neurons in the sympathetic system emerge from thoracic and lumbar segments, while parasympathetic ones arise from cranial nerves and sacral regions.

- This anatomical arrangement allows for targeted control, with ganglia located either near the spinal cord (sympathetic) or close to target organs (parasympathetic).

Anatomy of the Efferent Pathway

Efferent pathways in the ANS begin in the central nervous system and extend to peripheral effectors through a relay system. This structure contrasts with somatic pathways, which use a single neuron for direct innervation.

- The preganglionic neuron originates in the spinal cord’s lateral horn or brainstem nuclei, extending its myelinated axon to an autonomic ganglion.

- At the ganglion, synaptic transmission occurs via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, activating the postganglionic neuron.

- Postganglionic axons then travel to effectors like smooth muscle, where they release neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine (sympathetic) or acetylcholine (parasympathetic).

- Varicosities along these axons enable diffuse release, allowing one neuron to influence multiple cells simultaneously.

- In the diagram, the pathway is illustrated from the spinal cord to smooth muscle, emphasizing the transition from myelinated to unmyelinated fibers.

Physiological Mechanisms of Signal Transmission

Action potentials in autonomic efferent neurons propagate through electrochemical gradients, ensuring reliable communication. Neurotransmitter release at synapses and varicosities modulates effector function with precision.

- Depolarization in the preganglionic axon triggers calcium influx, leading to acetylcholine exocytosis at the ganglionic synapse.

- This binds to receptors on the postganglionic neuron, generating a new action potential that travels along the unmyelinated fiber.

- At the effector, sympathetic postganglionic neurons often release norepinephrine, which binds to adrenergic receptors to elicit responses like vasoconstriction.

- Parasympathetic counterparts use acetylcholine on muscarinic receptors, promoting effects such as bronchial constriction or increased glandular activity.

- The absence of a terminal synapse in many postganglionic axons, as shown in the varicosity label, allows for volume transmission, where neurotransmitters diffuse to nearby cells.

Functional Significance in Homeostasis

Homeostasis relies on the autonomic efferent pathway to adjust organ functions in response to internal and external changes. This pathway integrates sensory input to maintain equilibrium in vital parameters like blood pressure and temperature.

- For instance, during exercise, sympathetic activation via this pathway increases cardiac output and dilates airways.

- Conversely, after a meal, parasympathetic signals enhance peristalsis and secretion in the digestive tract.

- The two-neuron design provides opportunities for divergence, where one preganglionic neuron can activate multiple postganglionic ones, amplifying signals.

- Convergence also occurs, allowing integrated control from various central inputs.

- Disruptions in this pathway can lead to autonomic dysfunctions, though the diagram focuses on normal anatomy.

Comparative Analysis with Somatic Pathways

Unlike the autonomic system, somatic efferent pathways involve a single myelinated motor neuron from the spinal cord directly to skeletal muscle. This direct connection enables voluntary, precise movements without ganglionic relays.

- Autonomic pathways, as illustrated, use ganglia for modulation, allowing central integration before peripheral action.

- Somatic synapses use neuromuscular junctions with end-plate potentials, while autonomic ones employ varicosities for broader effects.

- Neurotransmitters differ: acetylcholine exclusively in somatic, versus varied in autonomic (acetylcholine and norepinephrine).

- Myelination in preganglionic autonomic axons mirrors somatic neurons for speed, but postganglionic lack it for diffuse signaling.

- This comparison underscores the autonomic system’s role in involuntary, widespread regulation.

Neurotransmitters and Receptors Involved

Acetylcholine serves as the primary neurotransmitter in preganglionic synapses for both sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions. Postganglionic transmission varies, contributing to diverse physiological outcomes.

- In sympathetic postganglionic neurons, norepinephrine activates alpha or beta adrenergic receptors on effectors.

- Parasympathetic postganglionic fibers release acetylcholine, binding to muscarinic receptors subtypes M1 through M5.

- These interactions can be excitatory or inhibitory, depending on the receptor and tissue.

- For example, beta-2 receptors in smooth muscle cause relaxation, aiding bronchodilation.

- Understanding these mechanisms is essential for pharmacology, as drugs like beta-blockers target these pathways.

Clinical Relevance of the Pathway

While the diagram depicts normal function, knowledge of the autonomic efferent pathway informs treatments for conditions like hypertension or gastrointestinal disorders. Interventions often modulate neurotransmitter activity or receptor binding.

- Anticholinergic drugs block muscarinic receptors to reduce parasympathetic effects, useful in overactive bladder.

- Sympathetic stimulants enhance norepinephrine release, applied in shock management.

- The pathway’s anatomy guides surgical approaches, such as sympathectomy for hyperhidrosis.

- Imaging techniques like MRI visualize spinal cord origins, aiding diagnosis of neuropathies.

- Overall, this foundational understanding supports advancements in autonomic research.

In summary, the autonomic efferent pathway exemplifies the intricate design of the nervous system, enabling seamless regulation of essential bodily functions. By appreciating its components—from the spinal cord to target effectors— one gains insight into the balance that sustains health, paving the way for further exploration in neuroscience.