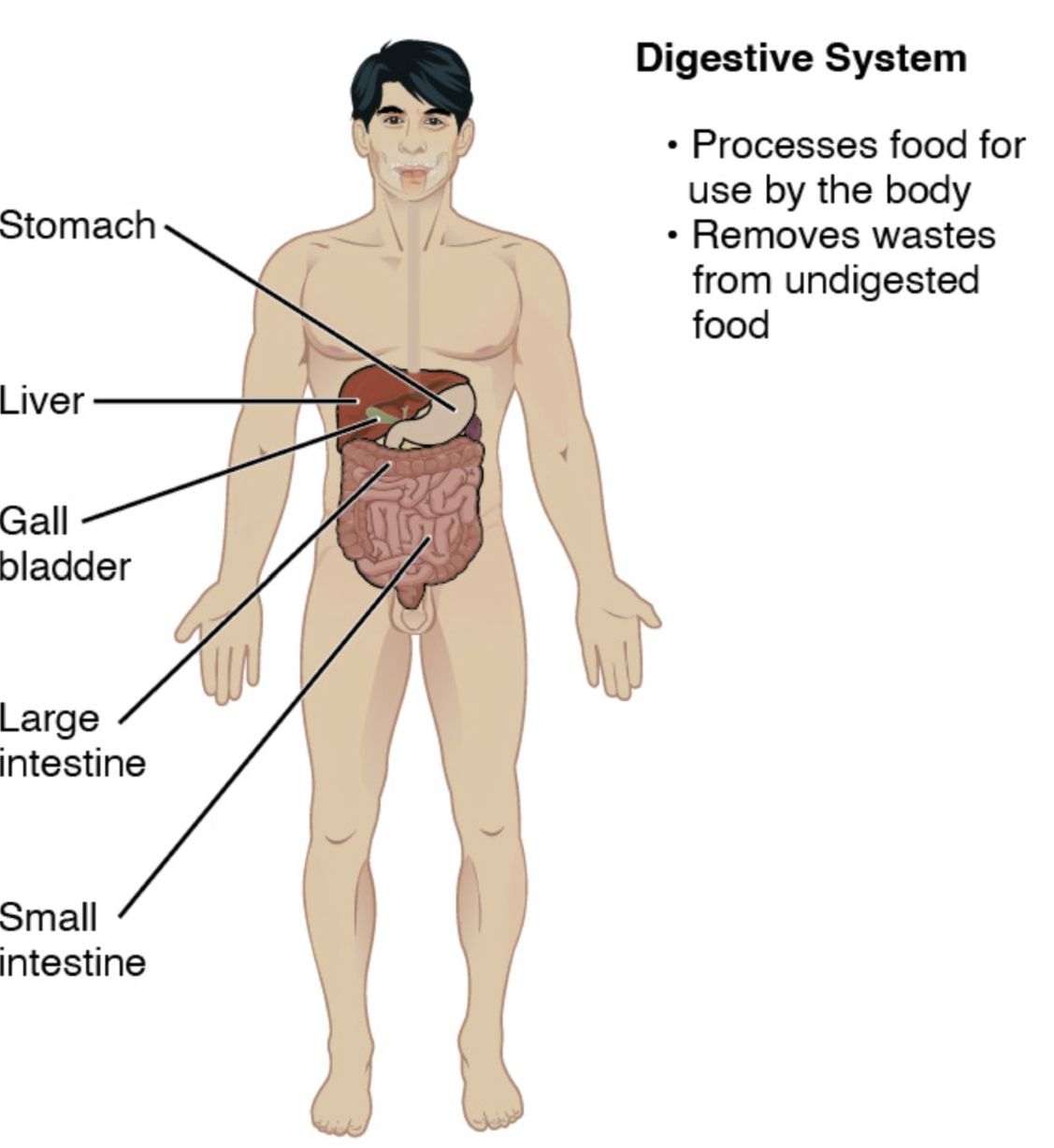

The digestive system is a complex network responsible for breaking down food, absorbing nutrients, and eliminating waste, playing a vital role in maintaining overall health. This diagram provides a detailed view of the organs involved, from the mouth to the rectum, showcasing their anatomical structure and functional relationships. Exploring this system offers a deeper appreciation of how the body processes sustenance and sustains life.

Key Labels in the Digestive System Diagram

This section outlines each labeled component, providing insight into its role within the digestive process.

Mouth: The entry point of the digestive system, where food is mechanically broken down by chewing and mixed with saliva containing amylase. It initiates carbohydrate digestion and prepares food for swallowing.

Esophagus: This muscular tube transports food from the mouth to the stomach through peristaltic movements. It prevents backflow with the lower esophageal sphincter, ensuring a one-way passage.

Stomach: A J-shaped organ that stores food, mixes it with gastric juices containing pepsin and hydrochloric acid, and begins protein digestion. It gradually releases partially digested food, or chyme, into the small intestine.

Small intestine: This long, coiled tube, divided into the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, is the primary site for nutrient absorption. Its large surface area, enhanced by villi and microvilli, maximizes absorption of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

Large intestine: This wider tube absorbs water and electrolytes, forming feces from indigestible material. It houses a diverse gut microbiota that aids in fermentation and vitamin production, such as vitamin K.

Liver: This large organ produces bile, which emulsifies fats for digestion, and detoxifies blood by metabolizing drugs and alcohol. It also stores glycogen and synthesizes proteins like albumin.

Gallbladder: A small sac that stores and concentrates bile produced by the liver, releasing it into the duodenum via the common bile duct. It plays a key role in fat digestion when triggered by fatty meals.

Pancreas: This gland secretes digestive enzymes like amylase, lipase, and protease into the duodenum to break down carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. It also releases insulin and glucagon to regulate blood sugar levels.

Rectum: The final section of the large intestine, where feces are stored before elimination. It signals the body for defecation through stretch receptors when full.

Anus: The external opening through which feces are expelled from the body, controlled by internal and external sphincter muscles. It marks the end of the digestive tract and waste elimination process.

Overview of the Digestive System’s Structure

The digestive system comprises a series of organs working in harmony. Its design ensures efficient nutrient processing and waste removal.

- The mouth begins digestion with salivary enzymes.

- The esophagus facilitates food movement to the stomach.

- The small intestine absorbs most nutrients with help from the liver and pancreas.

- The large intestine reabsorbs water, aided by the rectum and anus.

- Accessory organs like the gallbladder enhance fat digestion.

- This coordinated effort supports metabolic and excretory functions.

The Role of the Upper Digestive Tract

The upper digestive tract sets the stage for nutrient breakdown. It involves initial processing and transport.

- The mouth mechanically and chemically digests food with teeth and saliva.

- The esophagus uses peristalsis to move the bolus downward.

- The stomach acidifies food, activating pepsin for protein breakdown.

- Gastric emptying regulates the flow into the small intestine.

- Mucus protects the stomach lining from acid damage.

Functions of the Lower Digestive Tract

The lower digestive tract focuses on absorption and waste management. It completes the digestive process.

- The small intestine’s villi increase surface area for nutrient uptake.

- The large intestine reabsorbs water, forming solid waste.

- The rectum stores feces until elimination via the anus.

- Gut motility ensures efficient movement through these segments.

- The microbiome in the large intestine supports health.

Contribution of Accessory Organs

Accessory organs enhance digestive efficiency. They provide essential secretions and regulation.

- The liver produces bile to emulsify fats, aiding small intestine digestion.

- The gallbladder releases stored bile in response to dietary fats.

- The pancreas supplies enzymes and hormones like insulin.

- These organs work synergistically with the primary digestive tract.

- Imbalances can lead to conditions like gallstones or pancreatitis.

Physiological Importance and Clinical Relevance

The digestive system’s anatomy has significant physiological implications. It influences overall health and disease management.

- The liver detoxifies blood, impacting systemic health.

- The pancreas’s dual role supports digestion and glucose homeostasis.

- Disorders like irritable bowel syndrome affect the large intestine.

- Endoscopy examines the esophagus and stomach for issues.

- Dietary adjustments optimize small intestine nutrient absorption.

In conclusion, the digestive system anatomy diagram showcases a remarkable interplay of organs, from the mouth to the anus, each with specialized functions. The liver, gallbladder, and pancreas complement the primary tract, ensuring efficient digestion and nutrient utilization. Understanding this system’s structure and function is key to appreciating its role in sustaining health and addressing related disorders.