Discover the life-saving intervention of coronary stents, tiny mesh tubes used to open narrowed or blocked coronary arteries and restore vital blood flow to the heart muscle. This essential procedure helps treat coronary artery disease, preventing heart attacks and significantly improving cardiac function.

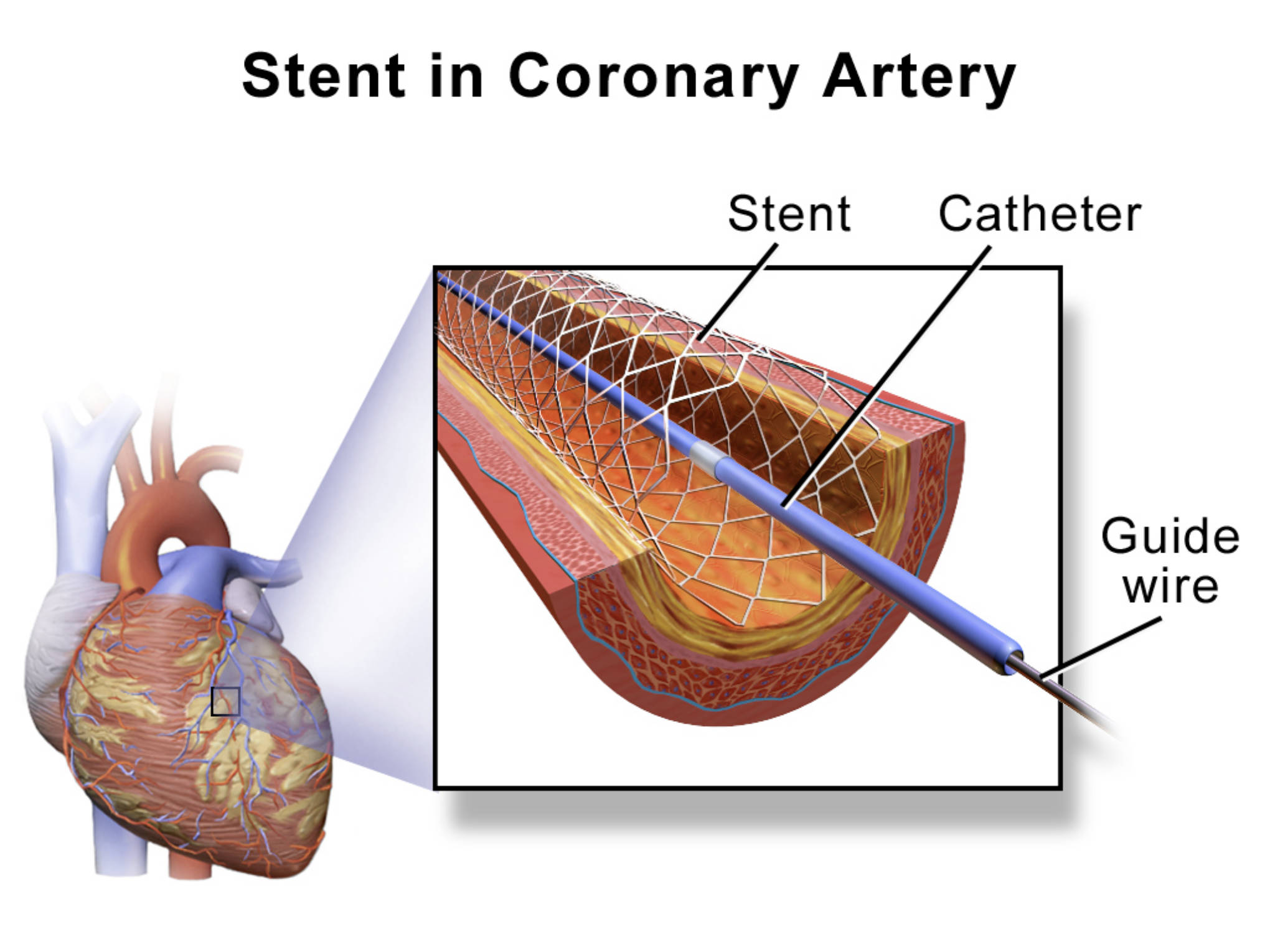

Understanding the Stent in Coronary Artery Diagram

Heart (left, general view): This overall view of the human heart shows its position within the chest and highlights the intricate network of coronary arteries on its surface. It provides the anatomical context for understanding where blockages occur and where stents are typically placed.

Stent: A small, expandable mesh-like tube, typically made of metal, that is inserted into a narrowed coronary artery. Once expanded, the stent acts as a scaffold to keep the artery open, preventing it from collapsing or re-narrowing.

Catheter: A thin, flexible tube used to deliver the stent to the site of the blockage in the coronary artery. The catheter is guided through blood vessels from an access point (usually in the wrist or groin) up to the heart.

Guide wire: A very thin, flexible wire that is first threaded through the blocked artery, past the narrowing. The catheter, carrying the stent, then slides over this guide wire to precisely reach the target lesion.

The Challenge of Coronary Artery Disease

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a widespread and serious condition characterized by the narrowing of the coronary arteries, the vital blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients directly to the heart muscle. This narrowing is primarily caused by atherosclerosis, a process where plaque (a buildup of cholesterol, fat, calcium, and other substances) accumulates on the inner walls of the arteries. As these plaques grow, they restrict blood flow, leading to symptoms such as chest pain (angina), shortness of breath, and fatigue, especially during physical exertion.

If a coronary artery becomes severely narrowed or completely blocked, often due to a ruptured plaque and subsequent blood clot formation, the heart muscle downstream of the blockage is deprived of oxygen. This critical event is known as a myocardial infarction, or heart attack, and can lead to irreversible damage to the heart muscle and potentially be fatal. For decades, treatment options for severe CAD were limited to bypass surgery, a highly invasive procedure.

However, advancements in interventional cardiology have revolutionized the treatment of CAD, offering less invasive approaches to restore blood flow. Among these, the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), often involving the placement of a coronary stent, has become a cornerstone therapy. Stents provide a crucial solution by mechanically propping open narrowed arteries, thereby improving blood supply to the heart muscle and significantly reducing the risk of heart attack and other serious cardiac events.

- Coronary artery disease (CAD) narrows heart arteries due to plaque.

- Severe narrowing can lead to myocardial infarction (heart attack).

- Coronary stents open blocked arteries.

- PCI with stent placement is a common treatment for CAD.

How a Coronary Stent Works

The process of implanting a coronary stent typically begins with a diagnostic procedure called an angiogram, which uses X-ray imaging and a contrast dye to visualize the coronary arteries and identify blockages. If a significant blockage is found, a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), also known as angioplasty with stenting, is performed. The procedure is usually carried out in a cardiac catheterization laboratory.

A thin, flexible guide wire is first inserted into an artery, typically in the wrist (radial artery) or groin (femoral artery), and carefully threaded under X-ray guidance to the heart and across the narrowed segment of the coronary artery. Over this guide wire, a specialized catheter with a deflated balloon at its tip is advanced to the site of the blockage. The balloon is then inflated, compressing the plaque against the artery walls and widening the lumen.

Once the artery is adequately opened, a coronary stent, which is usually mounted on another balloon catheter, is advanced over the same guide wire to the now-dilated segment. The balloon is then inflated again, expanding the mesh stent and pressing it firmly against the artery wall. The stent acts as a permanent scaffold, holding the artery open and preventing it from re-narrowing. After the stent is securely in place, the balloon is deflated and the catheter and guide wire are removed, leaving the stent behind to ensure sustained blood flow.

Types of Stents and Post-Procedure Care

There are two main types of coronary stents:

- Bare-metal stents (BMS): These are made of a plain metal alloy. While effective at physically opening the artery, there was a higher risk of re-narrowing (restenosis) due to excessive tissue growth within the stent.

- Drug-eluting stents (DES): These are bare-metal stents coated with a polymer that slowly releases anti-proliferative medications. These drugs inhibit the growth of smooth muscle cells, significantly reducing the incidence of restenosis and improving long-term patency of the artery. Drug-eluting stents are now the most commonly used type.

After stent implantation, patients are typically prescribed antiplatelet medications (such as aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor like clopidogrel) for several months to a year or more. This dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is crucial to prevent blood clots from forming on the surface of the new stent, a serious complication known as stent thrombosis. Lifestyle modifications, including a heart-healthy diet, regular exercise, smoking cessation, and strict management of risk factors like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes, are also essential to prevent the progression of coronary artery disease in other vessels and ensure the long-term success of the intervention. Regular follow-up appointments with a cardiologist are also vital to monitor the patient’s cardiac health and stent function.

Conclusion

Coronary stents represent a cornerstone of modern cardiovascular medicine, providing a remarkably effective and minimally invasive solution for managing coronary artery disease. By restoring crucial blood flow to the heart muscle, these tiny mesh devices alleviate symptoms, prevent life-threatening cardiac events like heart attacks, and significantly enhance the quality of life for millions of individuals. The continuous evolution of stent technology and percutaneous intervention techniques underscores the ongoing commitment to improving outcomes for patients grappling with this prevalent and serious condition.