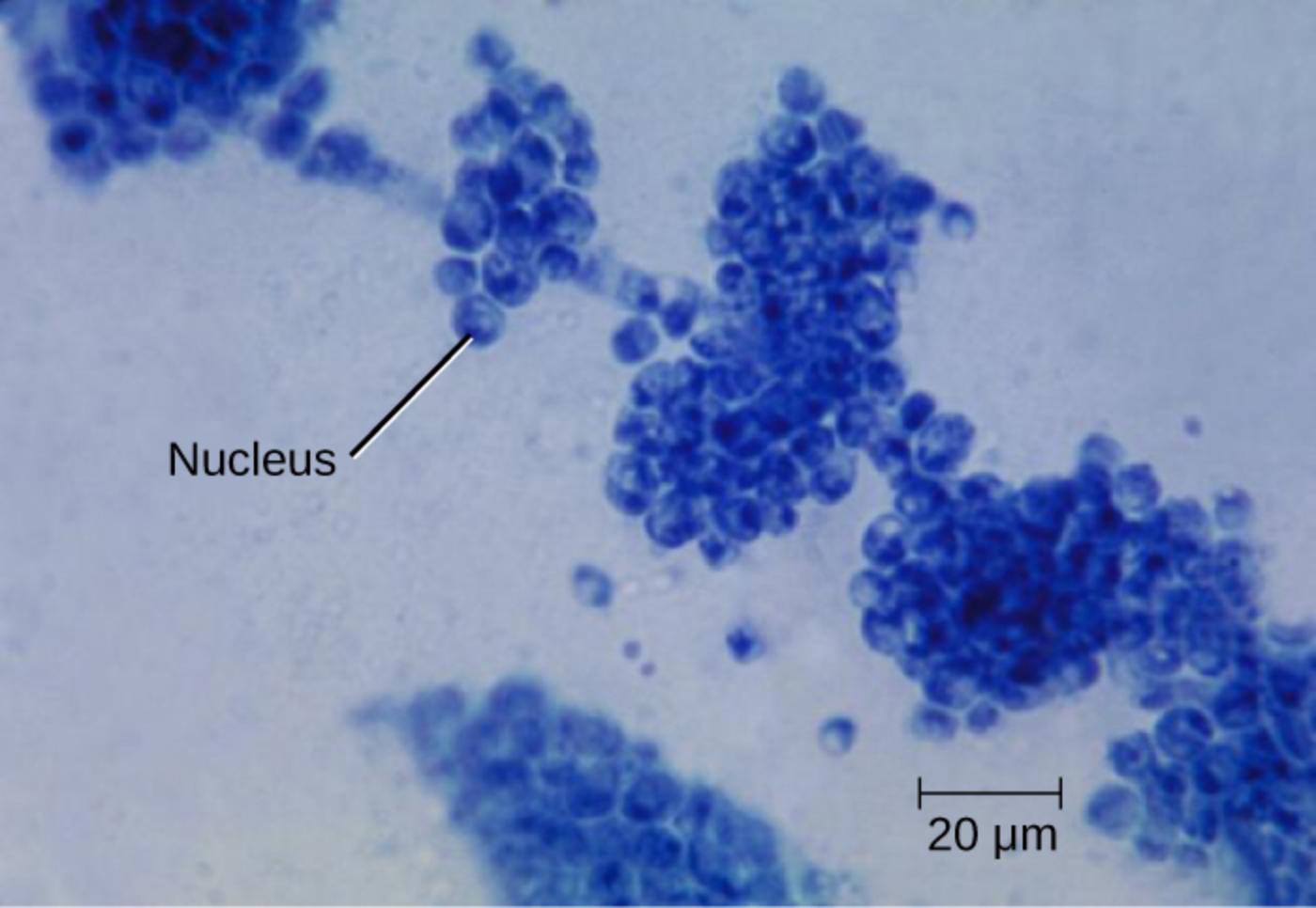

Candida albicans is a prevalent fungal pathogen that typically exists as a unicellular yeast but possesses the ability to cause significant localized and systemic infections in humans. This microscopic analysis highlights the eukaryotic nature of the organism, distinguishing it from bacteria through features like defined nuclei and a significantly larger cell size. Understanding the structural biology of this fungus is fundamental to diagnosing and treating common conditions such as oral thrush and vaginal candidiasis.

Nucleus: This structure is a membrane-bound organelle containing the genetic material of the cell, which clearly identifies the organism as a eukaryote. The presence of a visible, dark-stained nucleus within the cell distinguishes Candida albicans from prokaryotic organisms like bacteria, which lack a defined nuclear membrane.

20 μm: This scale bar represents a length of twenty micrometers and serves as a crucial reference for understanding the relative size of the yeast cells. It visually demonstrates that Candida cells are significantly larger than common bacteria, such as cocci, which typically measure only 0.5 to 1.0 micrometers in diameter.

Biological Characteristics of Unicellular Fungi

Candida albicans is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that is part of the normal human microbiota. In healthy individuals, it resides as a commensal organism on mucosal surfaces, including the oral cavity, the gastrointestinal tract, and the genitourinary system, without causing harm. However, disruptions in the host’s immune system or ecological balance can allow this yeast to proliferate uncontrollably, leading to infection.

Morphologically, C. albicans is a polymorphic organism. While the image provided displays the yeast form—round to oval cells often reproducing by budding—the organism can also switch to filamentous forms known as hyphae and pseudohyphae. This ability to change shape, or dimorphism, is a critical virulence factor, allowing the fungus to invade tissues and evade the immune system. Under the microscope, the cells may superficially resemble staphylococci (bacteria) due to their spherical shape and clustering, but their complex internal structure and larger size set them apart.

To better understand the nature of this organism, consider the following biological features:

- Eukaryotic Classification: Unlike bacteria, these cells contain complex organelles, including a distinct nucleus and mitochondria.

- Cell Wall Composition: The cell wall is primarily composed of chitin and glucans, distinct from the peptidoglycan found in bacterial cell walls.

- Reproduction: They reproduce asexually through a process called budding, where a new cell forms as an outgrowth of the parent cell.

- Habitat: They thrive in warm, moist environments within the body, such as the mouth and vaginal tract.

Distinguishing between fungal and bacterial infections is a cornerstone of clinical microbiology. Misidentification can lead to the inappropriate use of antibiotics, which are ineffective against fungi and may actually exacerbate a yeast infection by killing off beneficial competitive bacteria. Therefore, identifying the cellular features shown in the image, such as the nucleus, is vital for accurate diagnosis.

Pathogenesis of Candidiasis

When Candida albicans overgrows, it results in a condition collectively known as candidiasis. One of the most common manifestations is oral thrush (oropharyngeal candidiasis). This condition frequently affects infants, the elderly, and individuals with compromised immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or patients undergoing chemotherapy. Clinically, oral thrush presents as creamy white lesions on the tongue, inner cheeks, and the roof of the mouth. These patches can sometimes be scraped off, revealing a red, inflamed, and potentially bleeding base. In infants, this can lead to feeding difficulties and irritability.

Another prevalent form of infection is vulvovaginal candidiasis, commonly known as a vaginal yeast infection. This occurs when the natural balance of the vaginal microbiome is disturbed, often due to hormonal changes, uncontrolled diabetes, or the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Symptoms typically include intense pruritus (itching), irritation, and a characteristic thick, white, “cottage cheese-like” discharge that is usually odorless. While uncomfortable, these infections are generally localized and treatable with antifungal medications.

The treatment for these infections differs fundamentally from bacterial infections due to the eukaryotic nature of the fungal cells. Because fungi share many cellular mechanisms with human cells, developing drugs that target the fungus without harming the host is challenging. Treatments typically target unique components of the fungal cell membrane, such as ergosterol. Common antifungal agents include fluconazole, clotrimazole, and nystatin, which effectively disrupt the integrity of the yeast cell, leading to its death.

Conclusion

The microscopic examination of Candida albicans reveals a complex organism that is distinct from bacteria in both structure and behavior. While it is a common resident of the human microbiome, its potential to cause diseases like oral thrush and vaginal yeast infections necessitates careful clinical management. By recognizing the specific morphology—large, nucleated cells—medical professionals can accurately diagnose fungal infections and prescribe appropriate antifungal therapies, ensuring effective patient care and recovery.