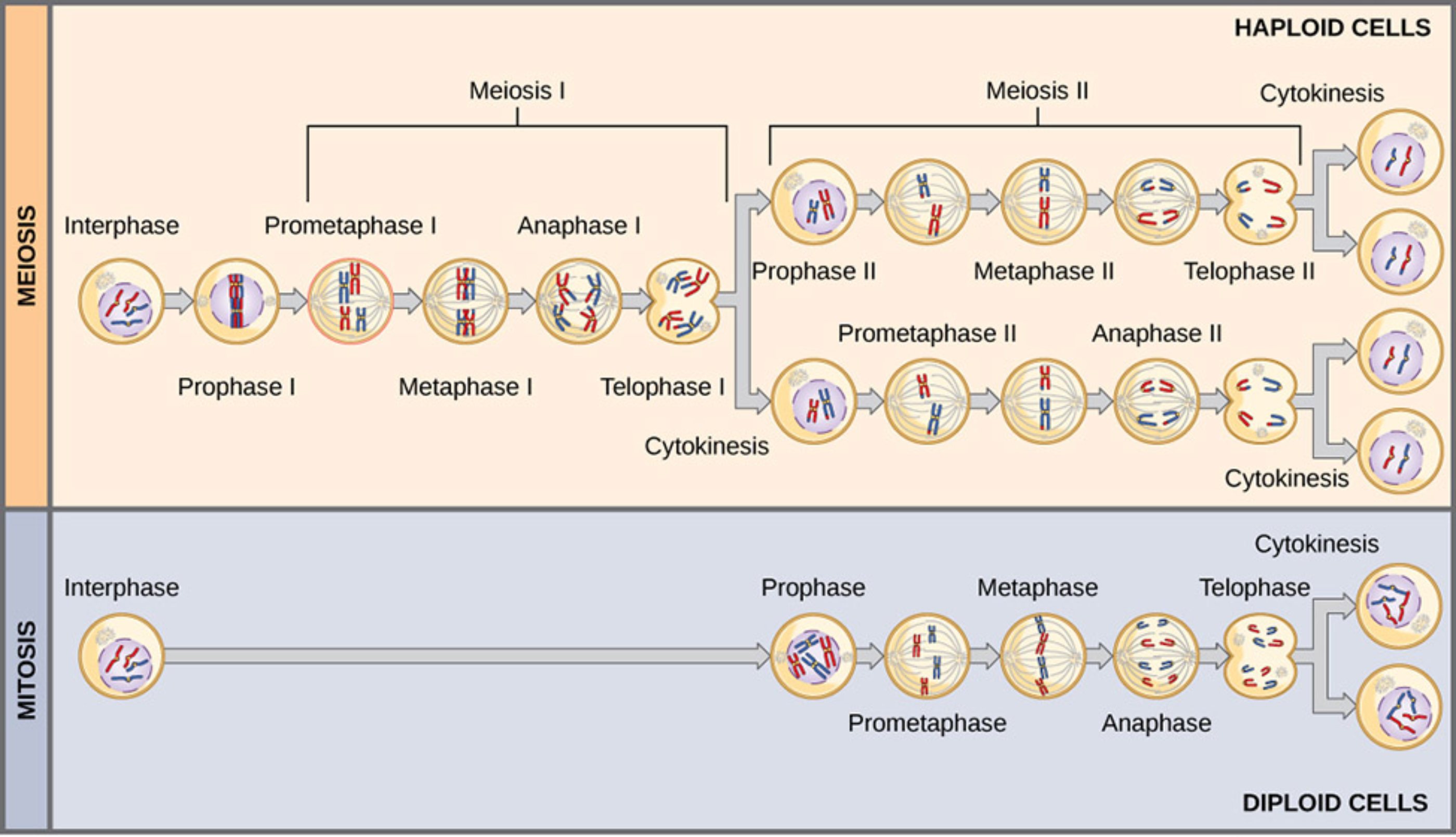

The following article explores the fundamental mechanisms of cell division, comparing the unique pathways of meiosis and mitosis to explain how organisms grow, repair tissue, and reproduce. This guide serves as a detailed reference for understanding chromosomal behavior and the biological significance of producing both diploid somatic cells and haploid gametes.

Interphase: This is the stage preceding cell division where the cell undergoes growth and DNA replication. It ensures that the genetic material is doubled so that each new daughter cell receives a complete set of genetic instructions.

Meiosis I: This is the first of two nuclear divisions in meiosis, characterized by the separation of homologous chromosomes. It is considered a reductional division because it halves the chromosome number from the diploid state to the haploid state.

Prophase I: During this stage, chromosomes condense and homologous pairs align closely to undergo a process known as synapsis. This phase is unique because it allows for crossing over, where segments of DNA are exchanged between non-sister chromatids to increase genetic variation.

Prometaphase I: The nuclear envelope completely breaks down, and spindle fibers attach to the kinetochores of homologous chromosomes. These fibers begin the mechanical process of moving the chromosome pairs toward the center of the cell.

Metaphase I: Homologous chromosome pairs line up along the metaphase plate in the center of the cell. The orientation of each pair is random, a phenomenon known as independent assortment, which further contributes to the genetic diversity of the resulting offspring.

Anaphase I: The spindle fibers contract and pull the homologous chromosomes apart to opposite poles of the cell. Unlike mitosis, the sister chromatids remain attached at their centromeres during this specific phase of division.

Telophase I: Chromosomes arrive at the poles, and the cytoplasm begins to constrict to prepare for division. In many species, a nuclear envelope temporarily reforms around the separated sets of chromosomes before moving into the next stage.

Cytokinesis: This is the physical process of cell division that partitions the cytoplasm and organelles into distinct daughter cells. In the context of meiosis, this process occurs twice to ultimately produce four separate haploid cells.

Meiosis II: This second round of division closely resembles mitosis because sister chromatids are separated rather than homologous pairs. This stage is essential for ensuring that the four resulting daughter cells each contain a single set of chromosomes.

Prophase II: The chromosomes condense again in the two haploid cells that were produced during the first meiotic division. A new spindle apparatus forms, preparing the sister chromatids for another round of separation.

Prometaphase II: Spindle fibers attach to the kinetochores of individual sister chromatids within the two haploid cells. The nuclear envelopes, if they had reformed after the first division, break down once again to allow for movement.

Metaphase II: Individual chromosomes, each consisting of two sister chromatids, align along the metaphase plate. This precise alignment is critical for ensuring that each of the final four daughter cells receives exactly one copy of each chromosome.

Anaphase II: Sister chromatids are finally pulled apart by the spindle fibers toward opposite poles of the cells. At this specific moment, each chromatid is officially considered an individual chromosome.

Telophase II: Nuclear membranes form around the four sets of separated chromosomes located at the cell poles. The chromosomes begin to decondense as the cells prepare for the final stage of cytokinesis and entry into interphase.

Haploid Cells: These are the final products of the meiotic process, containing only one set of chromosomes (n). In humans, these cells function as gametes—sperm and eggs—which are required for sexual reproduction and the fusion of genetic material.

Mitosis: This is the process of nuclear division in somatic cells that results in two genetically identical daughter cells. It is the primary mechanism for tissue growth, physiological development, and the routine repair of damaged cells throughout the lifespan.

Prophase: Chromatin condenses into visible chromosomes, and the mitotic spindle begins to assemble from the centrosomes. The nucleolus disappears, signaling that the cell has transitioned from growth to the active division phase.

Prometaphase: The nuclear envelope fragments into vesicles, allowing the spindle microtubules to access the chromosomes. Each chromosome develops a specialized structure for fiber attachment to ensure equal distribution later.

Metaphase: Chromosomes line up individually along the equatorial plane, or metaphase plate, of the cell. This alignment ensures that when the cell eventually divides, each daughter cell receives an identical and complete set of DNA.

Anaphase: Sister chromatids are separated at the centromere and pulled toward opposite ends of the cell. This phase is characterized by the rapid shortening of spindle fibers, ensuring the genetic material is partitioned perfectly.

Telophase: Two new nuclear envelopes form around the separated sets of daughter chromosomes at the poles. The chromosomes begin to uncoil back into a loose chromatin state, marking the completion of the nuclear division process.

Diploid Cells: These cells contain two complete sets of chromosomes (2n), with one set inherited from each parent. Most cells in the human body, such as those found in the skin and muscles, are diploid and are produced through mitotic division.

The Biological Significance of Meiosis and Mitosis

Cell division is a cornerstone of biological existence, enabling organisms to grow from a single zygote into complex multicellular beings. While the overarching goal is the distribution of genetic material, the specific mechanisms of mitosis and meiosis serve vastly different biological purposes. Mitosis focuses on maintaining genetic stability across generations of somatic cells, whereas meiosis is dedicated to the production of gametes for reproduction.

Key differences between these processes include:

- The number of nuclear divisions (one in mitosis, two in meiosis).

- The genetic composition of daughter cells (identical in mitosis, unique in meiosis).

- The final chromosome count (diploid in mitosis, haploid in meiosis).

- The occurrence of homologous pairing and crossing over (exclusive to meiosis).

In mitosis, a single round of DNA replication is followed by a single division, ensuring that somatic cells remain diploid. This process is highly regulated by various checkpoints to prevent mutations or chromosomal abnormalities that could lead to diseases such as cancer. Because the daughter cells are clones of the parent, mitosis allows for the consistent functioning and structural integrity of tissues and organs throughout the body.

Conversely, meiosis involves two successive divisions after one round of replication. The first division, Meiosis I, reduces the chromosome number by half through the separation of homologous pairs. The second division, Meiosis II, separates the sister chromatids. This intricate dance of DNA results in four haploid cells, providing the necessary genetic framework for fertilization where two haploid gametes fuse to restore the diploid state in the next generation.

Physiological Mechanisms and Genetic Diversity

The physiological significance of cell division cannot be overstated. In the human body, mitosis occurs millions of times every second to replace dead cells in the skin, intestinal lining, and blood. For instance, the cell cycle is a tightly controlled series of events that directs the growth and division of these cells. During mitosis, the spindle apparatus, composed of microtubules, plays a mechanical role in pulling chromosomes apart, ensuring that the 46 chromosomes in a human cell are partitioned accurately.

Meiosis, on the other hand, is restricted to the gonads—the testes in males and the ovaries in females. The physiological outcome is the creation of sperm and ova. One of the most critical events in Meiosis I is genetic recombination, which occurs during Prophase I. This process allows for the shuffling of maternal and paternal genes, which is why siblings (other than identical twins) are genetically distinct. This variation is the engine of evolution, allowing populations to adapt to changing environments and providing biological resilience.

Furthermore, the transition from diploid to haploid status is a fundamental physiological requirement for sexual reproduction. Without this reduction, the number of chromosomes would double with every generation, leading to genomic instability and cellular death. The precision of the kinetochore attachment to the spindle fibers during both mitosis and meiosis is what prevents aneuploidy, a condition where cells have an abnormal number of chromosomes, often leading to developmental disorders or miscarriage.

In summary, while mitosis and meiosis share several morphological stages, they are distinct processes tailored to the specific needs of the organism. Mitosis preserves the genetic blueprint for growth and repair, while meiosis reshuffles that blueprint to foster diversity and facilitate reproduction. Understanding these cellular mechanisms provides deep insight into human health, heredity, and the continuity of life itself.