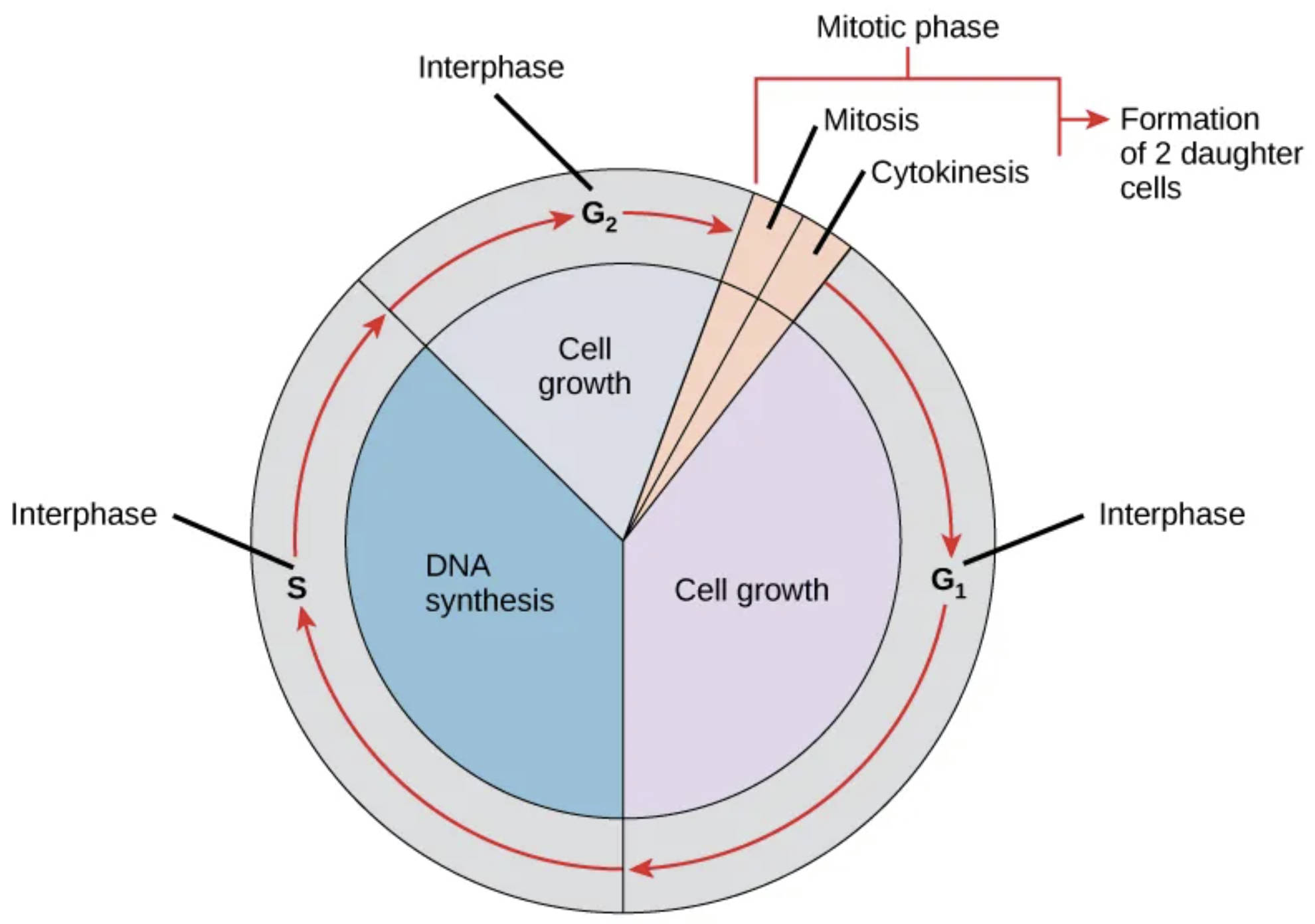

The cell cycle is an essential biological sequence that ensures the growth, repair, and reproduction of living organisms. By moving through meticulously regulated stages like interphase and the mitotic phase, cells can accurately duplicate their genetic material and divide into two functional daughter cells. This rhythmic progression is fundamental to maintaining homeostasis and ensuring that every tissue in the body receives a fresh supply of healthy, genetically identical cells.

Interphase: This is the longest part of the cell cycle, during which the cell prepares for division by growing and replicating its genetic material. It is subdivided into three distinct phases—G1, S, and G2—to ensure all necessary components are ready for the upcoming mitotic event.

G1 (Cell growth): Often called the first gap phase, this period is characterized by intense metabolic activity as the cell increases in size. During this time, the cell synthesizes various proteins and organelles required for the subsequent replication of DNA.

S (DNA synthesis): In this critical phase, the cell creates an exact copy of its entire genetic code through the process of DNA replication. This ensures that when the cell eventually divides, each daughter cell receives a complete and identical set of genetic instructions.

G2 (Cell growth): Known as the second gap phase, the cell continues to grow and produces the specific proteins and enzymes needed for chromosome movement. It also serves as a final checkpoint to ensure all DNA has been replicated correctly before entering the mitotic phase.

Mitotic phase: This relatively brief period of the cell cycle encompasses both nuclear division and the physical splitting of the cell. It is the stage where the intense preparation performed during interphase culminates in the actual creation of two new cellular units.

Mitosis: This process involves the systematic segregation of duplicated chromosomes into two separate nuclei within the parent cell. It consists of several highly organized sub-stages—prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase—to ensure that the genetic material is distributed with high fidelity.

Cytokinesis: Following the division of the nucleus, this phase involves the physical division of the cytoplasm and its remaining organelles. A contractile ring or cell plate forms to pinch the parent cell into two distinct entities, completing the reproductive cycle.

Formation of 2 daughter cells: This is the final result of the cell cycle, producing two genetically identical units from a single parent cell. These new cells then enter their own G1 phase, effectively restarting the cycle of life and growth from the beginning.

The Architecture of Cellular Growth and Division

The cell cycle is a fundamental process in eukaryotic organisms, governed by a series of precise biochemical signals and molecular checkpoints. It is not merely a random sequence of events but a highly coordinated progression that allows for the maintenance of multicellular life. From the moment a cell is formed until it divides, it must navigate these transitions to ensure that only healthy, error-free cells continue to proliferate. This cycle is crucial for replacing damaged tissues, facilitating embryonic development, and maintaining the overall health of an organism.

Regulation of the cycle is managed by specialized proteins known as cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. These molecules act as biological switches that push the cell forward or halt its progress if errors, such as DNA damage, are detected. If these control mechanisms fail, it can lead to uncontrolled proliferation, illustrating why understanding the standard cell cycle is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology and regenerative medicine.

Key components of the cell cycle include:

- Metabolic preparation and organelle duplication in the gap phases.

- High-fidelity replication of the entire genome during the synthesis phase.

- The structural reorganization of the cytoskeleton to facilitate chromosome movement.

- The equal partition of cytoplasmic resources between the two emerging cells.

The transition from interphase to the mitotic phase marks a significant shift in the cell’s physiological priorities. During interphase, the cell is primarily focused on internal expansion and protein synthesis. Once it crosses the threshold into mitosis, the focus shifts entirely to the physical mechanics of separation. This transition requires the condensation of chromatin into visible chromosomes, a process that protects the DNA from mechanical damage during the high-speed movements of nuclear division.

Physiological Regulation and Genomic Stability

The precision of the cell cycle is vital for preventing the accumulation of genetic mutations. During the S phase, the cell employs sophisticated proofreading enzymes that scan the newly synthesized DNA for errors. If a mistake is found, the cell pauses its progression, allowing repair mechanisms to fix the code before the cycle continues. This process of surveillance is one of the most important aspects of cellular physiology, as it protects the integrity of the organism’s blueprint across generations of cells.

Furthermore, the mechanics of mitosis are driven by the spindle apparatus, a network of microtubules that physically pulls the sister chromatids apart. This ensures that each nucleus in the emerging daughter cells receives exactly 46 chromosomes in humans. Any deviation in this number, known as aneuploidy, can have significant physiological consequences, highlighting the need for the absolute precision shown in the cell cycle diagram.

In summary, the cell cycle represents one of the most elegant and essential mechanisms in biology. By balancing growth, replication, and division, it allows life to persist and adapt to changing environmental demands. A deep understanding of each phase—from the quiet expansion of G1 to the dramatic division of cytokinesis—provides the essential framework for understanding human health at its most basic, microscopic level.