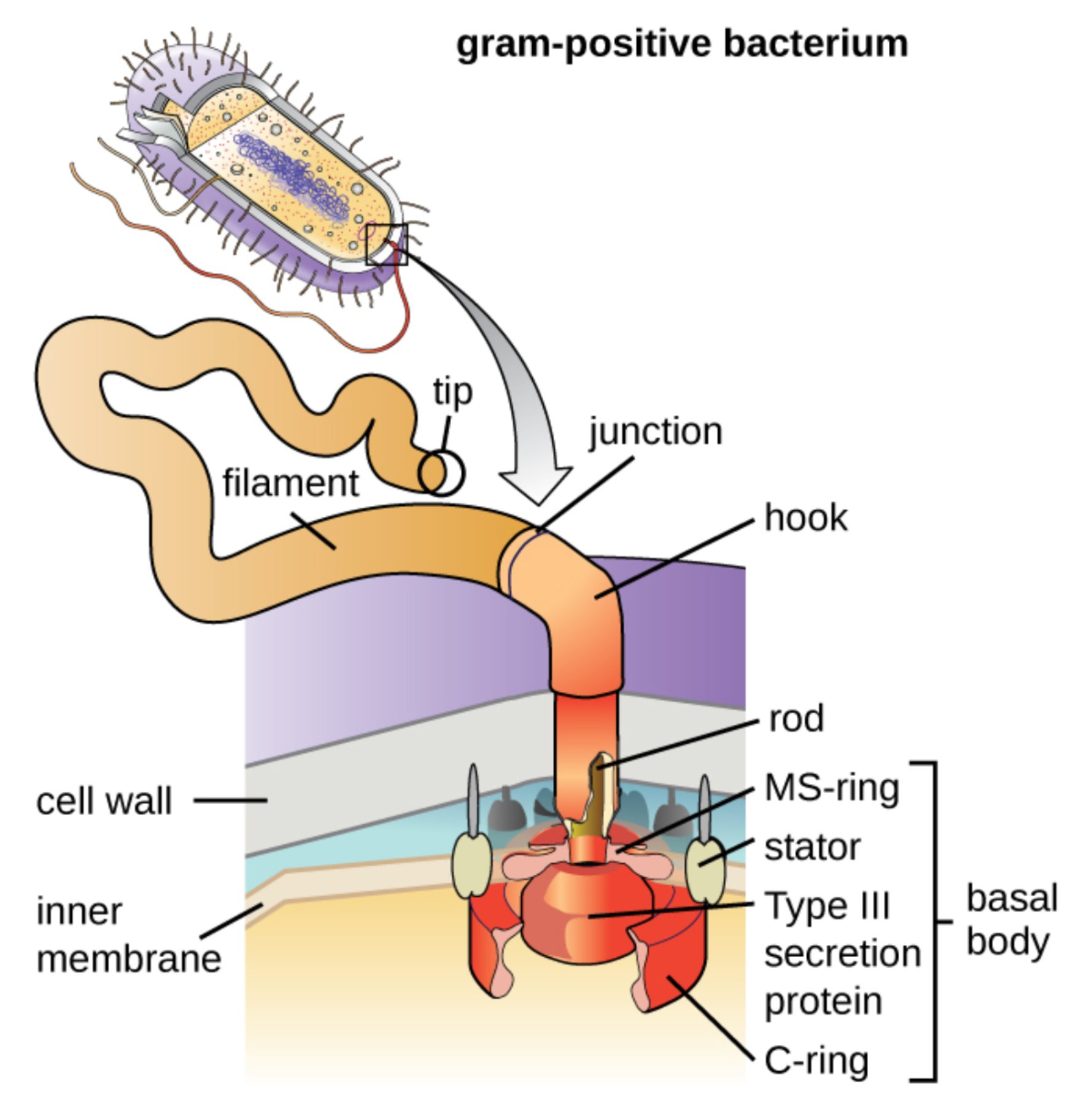

The bacterial flagellum is a marvel of biological engineering, serving as the primary organelle for motility in various microbial species. In Gram-positive bacteria, this complex rotary motor is anchored within a thick peptidoglycan cell wall and a single inner membrane, facilitating critical movements such as chemotaxis. Understanding its structural components, from the basal body to the external filament, is essential for comprehending how pathogens navigate host environments and establish infections.

tip: This is the distal cap of the flagellum where assembly takes place. It guides the incorporation of flagellin subunits as they are exported from the cell to extend the filament.

filament: The long, external propeller of the flagellum is composed of thousands of repeating protein subunits. It rotates at high speeds to generate the force required for cellular movement through aqueous environments.

junction: This transitional region connects the rigid filament to the flexible hook. It ensures a stable mechanical link while allowing for the seamless transfer of rotational energy.

hook: The hook functions as a universal joint, converting the torque from the internal motor into the circular motion of the filament. It is specifically designed to handle mechanical stress and maintain flexibility during rotation.

rod: This is the central axle of the flagellar motor that passes through the cell envelope. It transmits rotation from the cytoplasmic rotor assembly to the external propeller components.

MS-ring: This structural ring is embedded within the cytoplasmic membrane of the bacterium. It serves as the foundation for the rotor assembly and is a core part of the basal body system.

stator: The stator consists of stationary protein complexes that surround the rotor in the inner membrane. It harvests energy from ion gradients to generate the torque needed for flagellar movement.

Type III secretion protein: This component is part of the export apparatus located at the base of the flagellum. It is responsible for transporting structural proteins through the hollow center of the flagellum during its construction.

C-ring: Also known as the switch complex, this ring is located on the cytoplasmic side of the inner membrane. It controls the direction of rotation, allowing the bacterium to switch between forward movement and tumbling.

basal body: This is the entire motor assembly anchored within the cell’s boundary layers. It includes the rings, rod, and motor proteins required to drive the flagellum’s rotation.

cell wall: In Gram-positive bacteria, this is a thick layer of peptidoglycan that provides structural support and protection. The flagellar motor must be firmly anchored within this dense meshwork to remain stable during operation.

inner membrane: This is the selectively permeable phospholipid bilayer that encloses the cytoplasm. It serves as the site for the electrochemical gradient that powers the internal flagellar motor.

The Mechanical Logic of Microbial Movement

The bacterial flagellum represents one of nature’s most sophisticated examples of a molecular machine. Unlike eukaryotic flagella, which function through a sliding filament mechanism, the bacterial version is a true rotary engine. For Gram-positive bacteria, the lack of an outer membrane results in a more streamlined basal body structure compared to their Gram-negative counterparts, yet it remains equally effective at propelling the cell through varied biological niches.

This complex apparatus allows bacteria to perform chemotaxis, a process where the cell senses chemical gradients and moves toward nutrients or away from toxic substances. This movement is not just about survival in the environment; it is often the first step in the colonization of a human host. By swimming through mucus or across epithelial surfaces, motile bacteria can find the ideal sites for attachment and subsequent infection.

Key features of the Gram-positive flagellar assembly include:

- A motor powered by a proton motive force or sodium ion gradient.

- A hollow structure through which flagellin subunits are pumped for distal assembly.

- A basal body specifically anchored in a thick layer of protective sugars.

- A switch complex capable of changing rotational direction within milliseconds.

The assembly of the flagellum is a highly regulated and energy-intensive process. The cell must coordinate the expression of dozens of genes to ensure that each component is synthesized and secreted in the correct sequence. This genetic control ensures that the bacterium only invests energy in motility when the environmental conditions make it advantageous to do so.

Physiological Dynamics of the Flagellar Motor

The physiological heart of the flagellum is the motor anchored in the inner membrane. This motor harvests energy from the electrochemical gradient of protons (H+) or sodium (Na+) ions. As these ions flow through the stator proteins, they induce conformational changes that drive the rotation of the rotor. This rotational energy is then transferred up through the rod and hook to the external filament, acting much like a propeller on a boat.

The filament itself is composed of the protein flagellin. Interestingly, the flagellum grows from the tip rather than the base. Flagellin subunits are transported through the narrow, hollow center of the rod and hook until they reach the tip cap, where they are folded and integrated into the growing propeller. This unique “inside-out” construction method allows the bacterium to extend its flagellum several times its own body length, facilitating rapid transit through the host’s extracellular matrix.

Clinical Implications of Bacterial Motility

From a medical perspective, the flagellum is a critical component of virulence factors in many pathogenic species. Motility allows bacteria to invade deep tissues and escape the initial localized immune response. Furthermore, the protein flagellin is a potent stimulus for the innate immune system, recognized by specialized receptors on human cells that trigger inflammatory pathways.

In summary, the Gram-positive bacterial flagellum is a testament to the complexity of microscopic life, combining mechanical precision with biochemical efficiency. From the ion-powered stator to the self-assembling filament, every part is optimized for survival and movement. As medical science continues to investigate these structures, the flagellum remains a primary target for understanding microbial pathogenesis and developing innovative ways to impede bacterial colonization.