Osmotic pressure plays a vital role in maintaining the structural integrity of cells by regulating the movement of water across selectively permeable membranes. In medical and biological contexts, understanding how isotonic, hypertonic, and hypotonic solutions influence cellular volume is essential for everything from clinical fluid resuscitation to understanding basic physiological homeostasis.

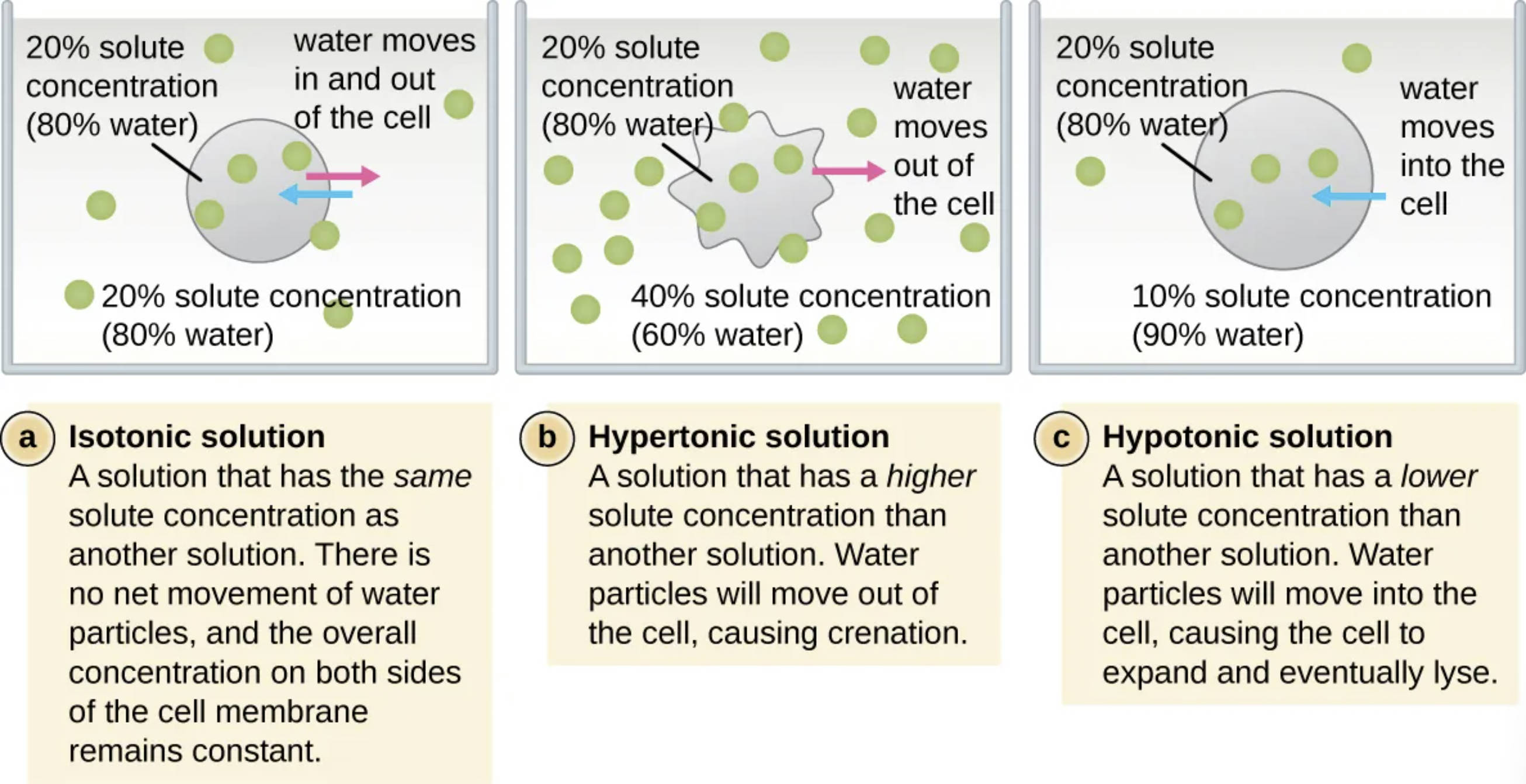

Isotonic solution: This is a solution that maintains the same solute concentration as the interior of the cell, resulting in no net movement of water. Because the osmotic pressure is balanced, the cell retains its normal shape and functional volume.

Hypertonic solution: This refers to an environment where the concentration of solutes outside the cell is higher than the concentration inside. As a result, water moves out of the cell via osmosis, causing the cell to shrink and undergo a process known as crenation.

Hypotonic solution: In this scenario, the surrounding solution has a lower solute concentration compared to the cell’s internal environment. Water molecules move into the cell, causing it to swell and potentially rupture in a process called lysis.

20% solute concentration (80% water): This label indicates a specific concentration level used as a reference point for comparing various osmotic environments in the diagram. It represents a state where the balance of water and dissolved particles is defined to demonstrate the direction of fluid movement.

40% solute concentration (60% water): This represents a highly concentrated external environment used to illustrate the mechanics of a hypertonic solution. The significantly lower water percentage outside the cell creates a gradient that pulls internal fluid toward the exterior.

10% solute concentration (90% water): This indicates a dilute external environment used to illustrate the effects of a hypotonic solution. The higher water percentage outside the cell drives water across the plasma membrane and into the cytoplasm.

water moves in and out of the cell: In an isotonic state, dynamic equilibrium is achieved where water molecules cross the membrane at equal rates in both directions. This ensures the overall concentration on both sides of the cell membrane remains constant and stable.

water moves out of the cell: When a cell is placed in a hypertonic medium, the osmotic gradient forces water toward the higher solute concentration found outside. This rapid loss of internal fluid leads to the characteristic shriveling of cells that lack a protective cell wall.

water moves into the cell: In a hypotonic medium, water flows naturally toward the higher solute concentration found within the cell’s interior. The resulting increase in internal pressure can cause the cell membrane to expand beyond its physical limit, eventually leading to cell death via lysis.

The Physiological Impact of Tonicity on Living Cells

Osmosis is a fundamental biological process involving the passive movement of water molecules through a semi-permeable membrane from an area of higher water concentration to an area of lower water concentration. This mechanism is critical for maintaining the health of living organisms, as it regulates the hydration levels and chemical balances within individual cells. For cells lacking a rigid cell wall, such as human red blood cells (erythrocytes), the external osmotic environment directly dictates their physical state and overall survivability.

The relationship between a cell and its surrounding fluid is described in terms of tonicity, which measures the effective osmotic pressure gradient between two solutions. Medical professionals must carefully consider tonicity when administering intravenous fluids to patients, as improper concentrations can lead to significant cellular damage or systemic complications. For example, “Normal Saline” (0.9% NaCl) is frequently used because it is isotonic to human blood, preventing unwanted shifts in cellular volume.

Factors that influence osmotic pressure in a clinical setting include:

- The concentration of electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and chloride in the blood.

- The presence of large molecules like proteins (e.g., albumin) that exert oncotic pressure.

- The permeability of the cell membrane to specific solutes and water.

- The rate of fluid intake and excretion by the kidneys.

When a cell encounters an imbalanced environment, it immediately responds to the osmotic gradient to seek equilibrium. In hypertonic environments, the cell loses water, which can impair metabolic processes and lead to cellular dehydration. Conversely, in hypotonic environments, the influx of water can cause mechanical failure of the membrane. Understanding these transitions is key to managing acute conditions like severe dehydration, water intoxication, or cerebral edema.

Cellular Anatomy and Resistance to Osmotic Stress

From an anatomical perspective, the plasma membrane serves as the primary barrier and regulator of osmolarity in animal cells. Unlike plants or bacteria, animal cells do not possess a rigid cell wall to provide structural support against internal pressure. This makes them particularly vulnerable to hypotonic environments, where the lack of a “back-pressure” mechanism means the cell will continue to expand until it reaches its breaking point. In medical terms, the bursting of red blood cells is specifically referred to as hemolysis, which can lead to anemia and kidney damage.

Physiologically, the body employs complex mechanisms to keep the extracellular fluid isotonic. The kidneys are the primary organs responsible for this regulation, filtering the blood and adjusting the amount of water and salts excreted in the urine. By sensing changes in blood volume and solute concentration, the endocrine system releases hormones like antidiuretic hormone (ADH) to preserve water balance. This ensures that the cells of the brain, heart, and other vital organs are not subjected to the damaging effects of crenation or lysis.

In the laboratory, these osmotic principles are used to study cell membrane permeability and to isolate specific cellular components. By carefully adjusting the solute concentration of a medium, researchers can purposefully induce lysis to release internal organelles or DNA for analysis. This highlights how the same physical laws that govern human health can be harnessed as a powerful tool in molecular biology and diagnostic research.

The delicate balance of osmotic pressure is a cornerstone of cellular biology and clinical medicine. By regulating the movement of water, organisms ensure that their cells remain functional and structurally sound across varying environmental conditions. Whether in a laboratory or a hospital ward, a thorough grasp of isotonic, hypertonic, and hypotonic dynamics is essential for preserving the life-sustaining processes of the cell and ensuring patient safety during treatment.