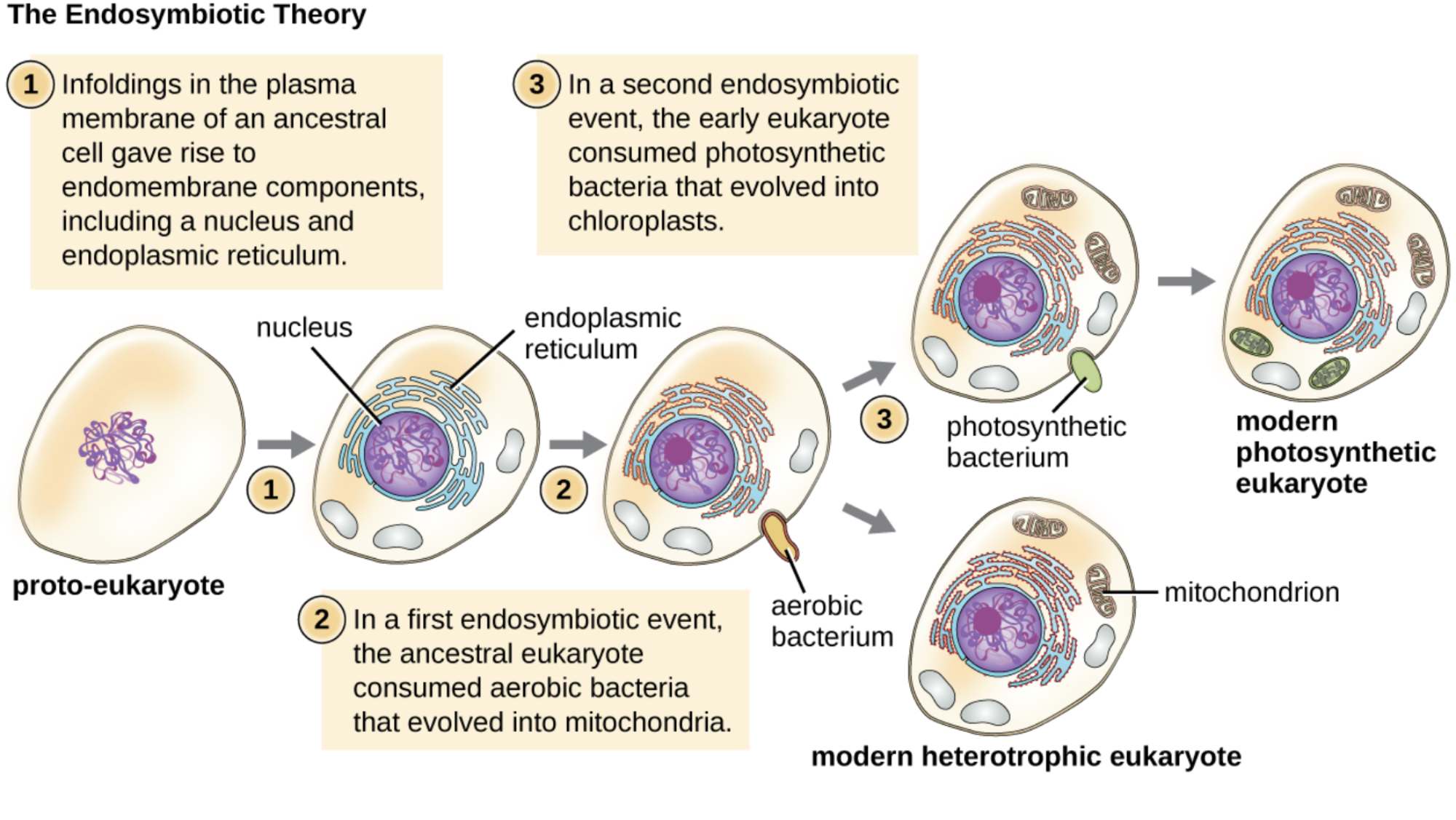

The endosymbiotic theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how complex eukaryotic life emerged from simple, single-celled prokaryotic ancestors. This biological transition was characterized by the internal folding of cellular membranes and a unique symbiotic relationship where one organism began living inside another, eventually leading to the formation of specialized organelles.

Proto-eukaryote: This term refers to an ancestral cell that existed before the development of complex membrane-bound organelles. It represents the early evolutionary stage where cells lacked a defined nucleus and mitochondria.

Nucleus: The nucleus is the primary regulatory center of the cell, housing the majority of its genetic material in the form of DNA. According to the theory, this structure originated from the inward folding of the plasma membrane in an ancestral cell.

Endoplasmic reticulum: This organelle consists of a vast network of membranous sacs and tubules responsible for protein and lipid synthesis. It is believed to have evolved simultaneously with the nucleus as part of the internal endomembrane system development.

Aerobic bacterium: This was a primitive, free-living prokaryote capable of using oxygen to generate energy. When engulfed by a proto-eukaryote, it avoided digestion and established a mutually beneficial relationship, eventually becoming a permanent part of the host.

Photosynthetic bacterium: These organisms, similar to modern-day cyanobacteria, possessed the ability to convert sunlight into chemical energy through photosynthesis. Their engulfment by early eukaryotes marked the second major endosymbiotic event in evolutionary history.

Mitochondrion: Often described as the “powerhouse of the cell,” this organelle is responsible for generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through aerobic respiration. Its double membrane and independent genome serve as strong evidence for its bacterial origins.

Modern heterotrophic eukaryote: This classification includes complex cells that contain a nucleus and mitochondria but lack chloroplasts. These cells, which form the basis of animal and fungal life, must consume organic matter to obtain energy.

Modern photosynthetic eukaryote: These are advanced cells that contain both mitochondria and chloroplasts, allowing them to perform both respiration and photosynthesis. This lineage gave rise to the diverse world of plants and algae seen today.

The transition from prokaryotic life to the vast complexity of eukaryotes is one of the most critical events in the history of biology. For billions of years, life on Earth consisted solely of simple, single-celled organisms without specialized internal compartments. The endosymbiotic theory, pioneered largely by biologist Lynn Margulis, suggests that the complexity we see in modern plants and animals began when these simple cells started to cooperate and merge.

This evolutionary pathway did not happen all at once but occurred in several distinct stages. Initially, the plasma membrane of an ancestral prokaryote began to fold inward, creating internal compartments like the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum. This allowed the cell to protect its DNA and segregate chemical reactions, increasing its physiological efficiency. Following this, the cell underwent a process of endocytosis, where it engulfed smaller bacteria that were not digested but instead became internal partners.

There are several key pieces of evidence that support this theory and highlight the bacterial ancestry of our internal organelles:

- Mitochondria and chloroplasts contain their own circular DNA, distinct from the DNA found in the cell nucleus.

- These organelles reproduce independently of the rest of the cell through a process known as binary fission, much like modern bacteria.

- Both mitochondria and chloroplasts are surrounded by a double membrane, suggesting they were once engulfed by a host cell’s membrane.

- The ribosomes found within these organelles are more similar in size and structure to bacterial ribosomes than to those found in the eukaryotic cytoplasm.

The first endosymbiotic event involved the consumption of aerobic bacteria. These bacteria were highly efficient at using oxygen to produce energy, a trait that the host cell lacked. In exchange for protection and a steady supply of nutrients, the bacteria provided the host with a massive surge in available energy. This partnership was so successful that the bacteria eventually lost their independence, evolving into the mitochondria found in nearly all eukaryotic cells today. This event laid the groundwork for the emergence of multicellular organisms.

A second endosymbiotic event occurred in a separate lineage, where an early eukaryote that already possessed mitochondria engulfed a photosynthetic bacterium. This allowed the cell to harness energy directly from sunlight, a process known as eukaryogenesis that led to the development of chloroplasts. This specific evolutionary branch gave rise to the entire plant kingdom, fundamentally changing the Earth’s atmosphere by increasing oxygen levels and providing the foundation for modern terrestrial ecosystems.

The legacy of endosymbiosis is visible in every breath we take and every bit of energy our bodies consume. By understanding these ancient cellular mergers, we gain insight into the fundamental interconnectedness of life. The evolution of the endomembrane system and the integration of foreign bacteria transformed life from simple, competing microbes into the complex, cooperative systems that define the natural world today.