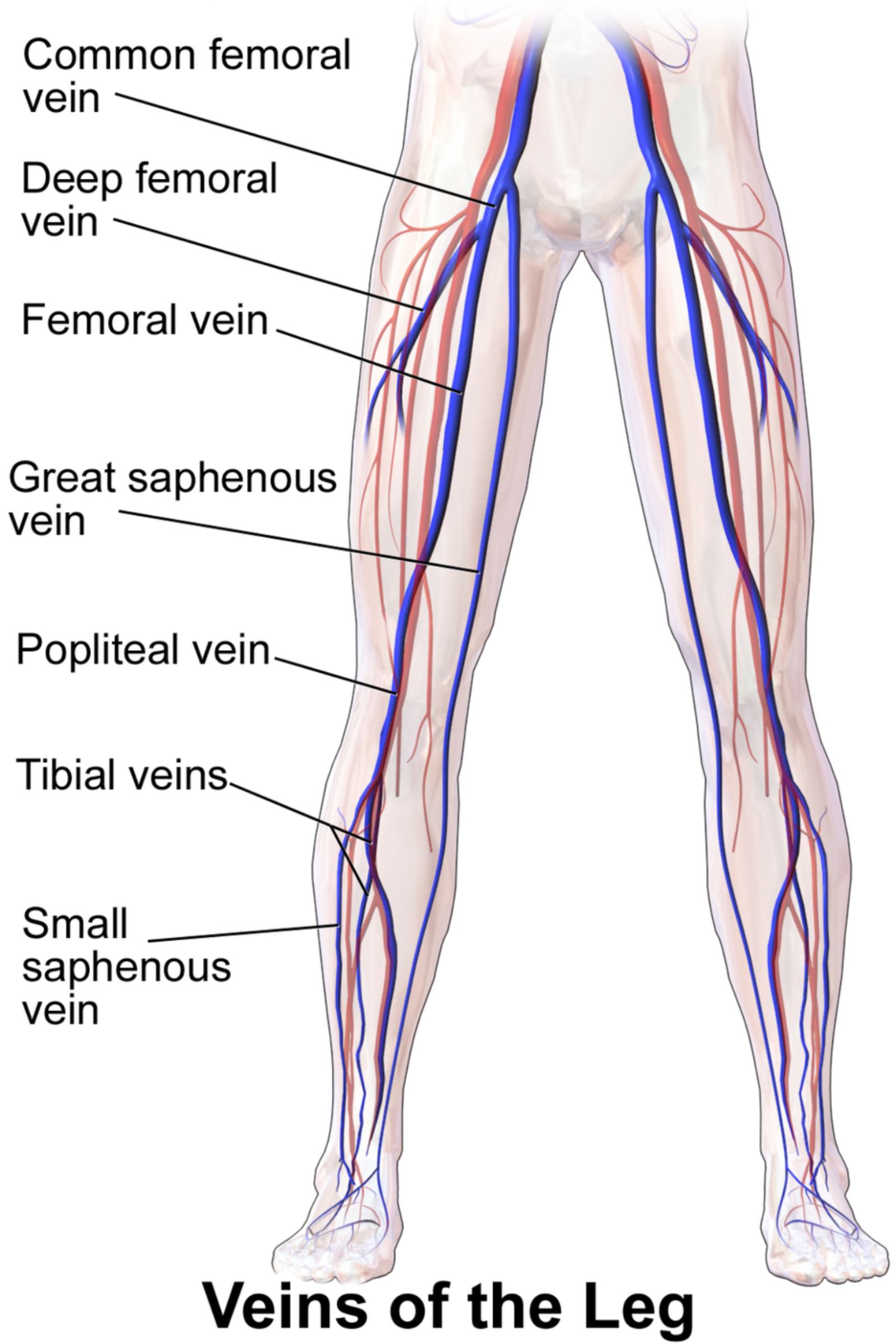

The venous system of the lower extremities is a complex and highly specialized network designed to return deoxygenated blood to the heart against the constant pull of gravity. This system is divided into deep, superficial, and perforating veins, all of which contain one-way valves to ensure unidirectional blood flow. Understanding the specific pathways and names of these vessels is essential for recognizing how the body maintains circulatory balance and prevents fluid accumulation in the limbs.

Common femoral vein: This is a major deep vein located in the upper thigh and groin area, formed by the convergence of the femoral and deep femoral veins. It serves as a primary drainage route for the lower limb and becomes the external iliac vein once it passes superiorly beyond the inguinal ligament.

Deep femoral vein: Also referred to as the profunda femoris vein, this vessel travels deep within the thigh to drain blood from the large muscle groups in that region. It runs parallel to the deep femoral artery and provides an essential pathway for venous return from the posterior and lateral compartments of the leg.

Femoral vein: Although its name might suggest a superficial location, this is actually a major deep vein that accompanies the femoral artery through the thigh. It carries the vast majority of blood from the lower leg back toward the torso and is a frequent site of interest during vascular ultrasound examinations.

Great saphenous vein: As the longest vein in the human body, this vessel runs superficially along the medial aspect of the entire leg, from the foot up to the groin. It is clinically significant because it is often harvested for use in cardiac bypass surgeries due to its length and accessibility.

Popliteal vein: Situated directly behind the knee in the popliteal fossa, this vein is formed by the union of the anterior and posterior tibial veins. It acts as a critical transition point, receiving blood from the lower leg and continuing upward to become the femoral vein as it enters the thigh.

Tibial veins: These are deep veins in the lower leg, specifically the anterior and posterior tibial veins, which follow the paths of their corresponding arteries. They are responsible for collecting deoxygenated blood from the foot and calf muscles, often appearing as pairs known as venae comitantes.

Small saphenous vein: This is a superficial vein that begins at the lateral side of the foot and travels up the back of the calf. It typically terminates by piercing the deep fascia and emptying its contents into the popliteal vein behind the knee.

The Physiology of Lower Limb Venous Return

The architecture of the leg veins is uniquely adapted to overcome the challenges of upright posture. Unlike arteries, which rely on the high-pressure pumping of the heart, veins operate under much lower pressure. To move blood upward, the body utilizes a mechanism known as the calf muscle pump, where the contraction of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles squeezes the deep veins, forcing blood toward the heart. During muscle relaxation, the one-way valves close to prevent “reflux,” or the backward flow of blood toward the feet.

The health of this system depends heavily on valvular competence, which ensures that blood does not pool in the lower extremities. If these valves become damaged or weakened, it can lead to a condition known as chronic venous insufficiency, characterized by swelling, skin changes, and the development of varicose veins. The superficial system, including the great and small saphenous veins, works in harmony with the deep system via perforating veins that bridge the two layers.

Several factors can influence the efficiency of venous return and the overall health of the leg’s vascular network:

- Physical activity levels and frequency of muscle contraction.

- Body weight and the resulting pressure on pelvic veins.

- Age-related changes in the elasticity of vessel walls.

- Genetic predispositions to structural valve weakness.

- Environmental factors, such as prolonged standing or sitting.

In clinical practice, the deep veins are monitored closely because they are the most common sites for deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Because the deep veins carry about 90% of the blood back from the legs, a blockage in these vessels can have significant systemic consequences, including the risk of a pulmonary embolism. Conversely, the superficial veins, while less likely to cause life-threatening clots, are more prone to aesthetic and symptomatic issues like phlebitis or varicosities.

Maintaining healthy leg veins is a cornerstone of overall cardiovascular wellness. By supporting the natural mechanisms of the venous system through regular movement and proper hydration, individuals can reduce the risk of circulatory complications. A thorough understanding of this anatomy allows healthcare providers to accurately diagnose vascular disorders and implement effective treatments to preserve limb health and systemic circulation.