This article provides a detailed clinical analysis of a medical ultrasound scan revealing a thrombus within the left common femoral vein. We will explore the radiological appearance of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), the anatomical significance of the femoral vasculature, and the pathophysiology of venous clotting disorders. Understanding these imaging findings is essential for the timely diagnosis and management of thromboembolic conditions, which prevents severe complications such as pulmonary embolism.

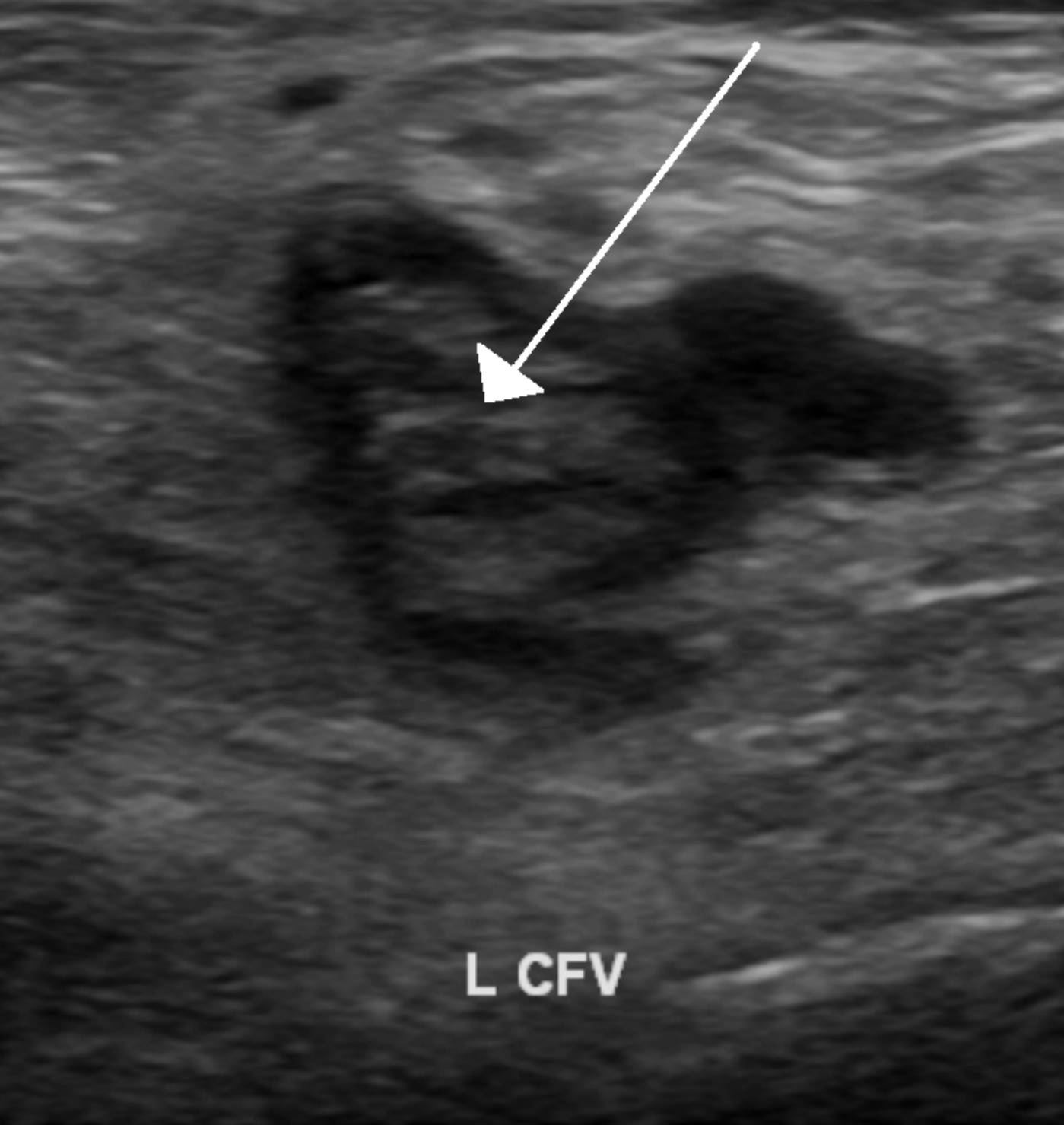

White Arrow (Thrombus): The white arrow points to an intraluminal mass that appears heterogeneous and echogenic (brighter than the surrounding fluid). This structure is the blood clot itself, which occupies the vessel lumen and prevents the normal flow of blood, a hallmark sign of thrombosis on an ultrasound.

L CFV (Left Common Femoral Vein): This label identifies the specific anatomical location of the image, the left common femoral vein. This is a major deep vein in the upper thigh that is formed by the confluence of the femoral vein and the deep femoral vein, serving as a critical pathway for venous return from the lower extremity to the heart.

Understanding Deep Vein Thrombosis and Ultrasound Imaging

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) is a serious medical condition characterized by the formation of a blood clot (thrombus) within a deep vein, most commonly in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis. The image provided illustrates a classic presentation of DVT in the common femoral vein. Under normal physiological conditions, veins on an ultrasound appear as anechoic (black) fluid-filled structures that are easily compressible. However, when a clot is present, the vein typically expands, becomes non-compressible, and contains visible internal echoes, as seen in the labeled scan.

Ultrasound, specifically compression ultrasonography (CUS) often combined with Doppler, is the gold standard diagnostic tool for identifying DVT. It is non-invasive, widely available, and highly sensitive for proximal vein thrombosis. Sonographers look for the “loss of compressibility” as the primary diagnostic criterion. If the ultrasound probe presses down on the skin and the vein walls do not touch due to a solid mass inside, a diagnosis of thrombosis is confirmed.

The location of the clot in the common femoral vein is particularly significant clinically. Proximal clots (those in the popliteal vein and above, including the femoral and iliac veins) carry a much higher risk of breaking loose and traveling to the lungs than distal clots in the calf. Therefore, identifying a blockage in the L CFV requires immediate medical intervention to stabilize the clot.

Risk factors for developing a DVT generally fall under Virchow’s Triad, which includes:

- Venous Stasis: Slow blood flow due to immobility, surgery, or long-distance travel.

- Endothelial Injury: Damage to the blood vessel wall from trauma, catheters, or surgery.

- Hypercoagulability: A biological tendency to clot easily due to genetics, cancer, pregnancy, or hormonal medications.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications of DVT

Deep Vein Thrombosis occurs when the hemostatic balance of the body is disrupted. Normally, the body maintains blood in a fluid state while being ready to clot if a vessel is injured. In DVT, the coagulation cascade is triggered inappropriately within an intact vein. Fibrin mesh and platelets aggregate to form a solid mass. As the clot grows, it can partially or completely obstruct venous return, leading to back pressure in the leg. This results in the classic symptoms of DVT: unilateral swelling (edema), pain or cramping, warmth, and erythema (redness) of the affected limb.

The most feared complication of a DVT is a pulmonary embolism (PE). This occurs when a portion of the thrombus, known as an embolus, detaches from the vein wall. It travels through the inferior vena cava, passes through the right side of the heart, and lodges in the pulmonary arteries. A PE can block blood flow to the lungs, causing low oxygen levels, heart strain, and potentially cardiac arrest. Because the common femoral vein is a large caliber vessel, clots formed here can be substantial in size, increasing the potential severity of a resulting embolism.

Treatment and Management Protocols

Once a DVT is confirmed via ultrasound, the primary goal of treatment is to prevent the clot from getting larger and to stop it from breaking loose. The cornerstone of therapy is anticoagulation. Physicians typically prescribe medications such as low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) like apixaban or rivaroxaban. These drugs do not dissolve the clot directly; rather, they stop the clotting process, allowing the body’s natural fibrinolytic system to slowly break down the thrombus over weeks or months.

In severe cases, or where anticoagulation is contraindicated, more aggressive interventions may be necessary. This can include the placement of an Inferior Vena Cava (IVC) filter to catch clots before they reach the lungs, or thrombolytic therapy (“clot-busting” drugs) to actively dissolve the blockage. Long-term management often involves the use of compression stockings to prevent Post-Thrombotic Syndrome, a chronic condition causing persistent pain and swelling in the leg due to valve damage from the original clot.

Conclusion

The ultrasound image of the left common femoral vein provides a definitive view of a pathological thrombus. Recognizing the echogenic appearance of the clot within the vessel lumen allows healthcare providers to diagnose deep vein thrombosis accurately and initiate life-saving treatment. By understanding the anatomy of the femoral veins and the risks associated with venous thromboembolism, medical professionals can effectively manage patients to prevent fatal complications like pulmonary embolism.