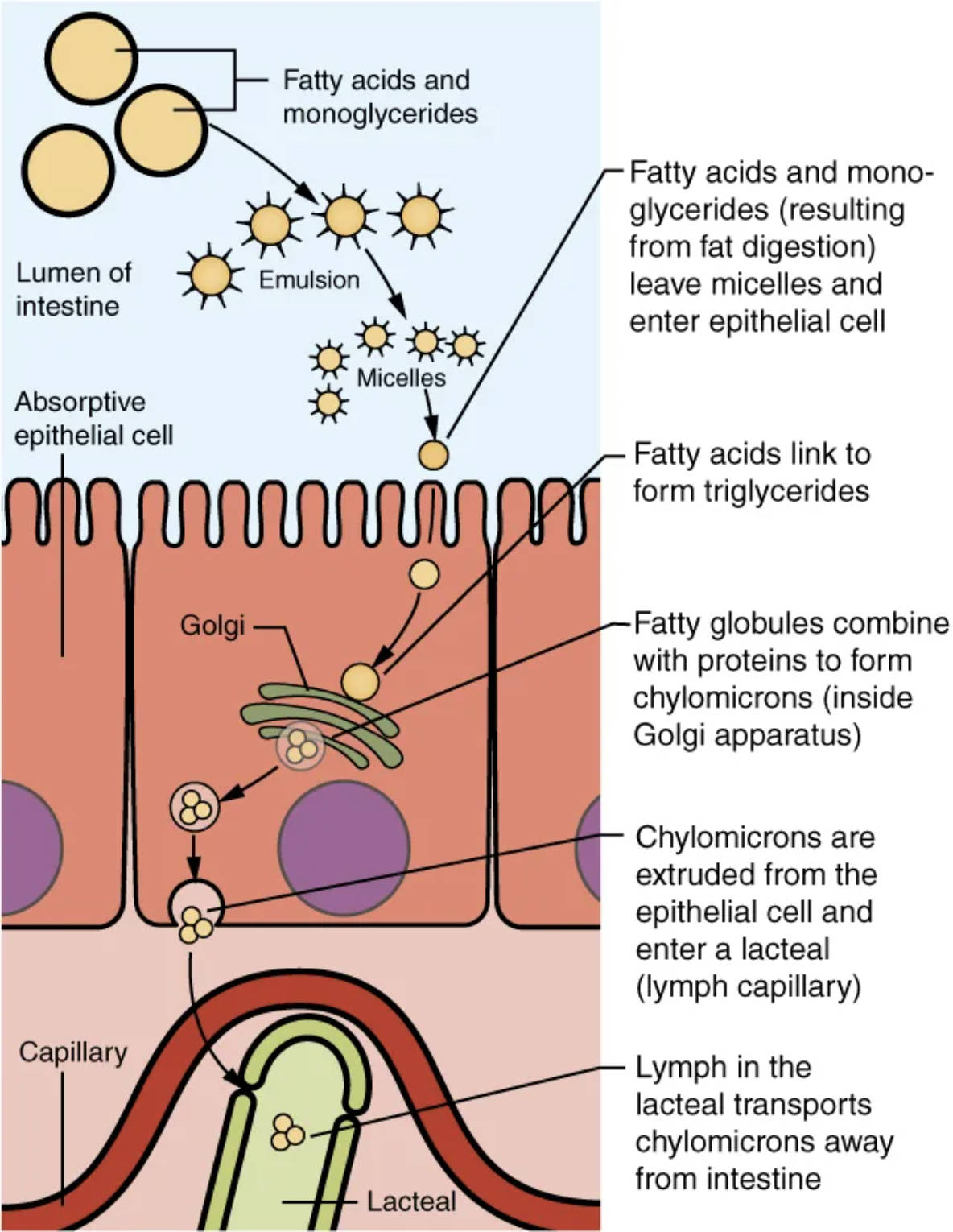

The digestion and absorption of dietary fats, or lipids, represent one of the most intricate processes within the human digestive system. Unlike water-soluble nutrients, fats require a specialized pathway to traverse the aqueous environment of the intestinal lumen and enter the bloodstream. This detailed diagram meticulously illustrates the sequential steps of lipid absorption, from the initial formation of emulsions and micelles to the packaging of chylomicrons and their transport via the lymphatic system. Grasping this sophisticated mechanism is crucial for understanding nutrient assimilation and various malabsorption disorders.

Fatty acids and monoglycerides: These are the primary end products of fat digestion in the small intestine, resulting from the enzymatic breakdown of triglycerides. They are amphipathic molecules, meaning they have both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions, which allows them to interact with both water and fats.

Lumen of intestine: This is the internal space within the small intestine where digested food, enzymes, and bile mix. It is the site where the initial breakdown of dietary fats into fatty acids and monoglycerides occurs.

Emulsion: A mixture of two immiscible liquids, like oil and water, where one is dispersed in the other in the form of tiny droplets. In the intestine, bile salts emulsify large fat globules into smaller droplets, increasing their surface area for enzyme action.

Micelles: Small, spherical aggregates formed by bile salts, fatty acids, monoglycerides, and fat-soluble vitamins in the lumen of the small intestine. They are crucial for transporting hydrophobic lipids through the aqueous environment to the absorptive epithelial cells.

Absorptive epithelial cell: These are the specialized cells lining the small intestine, responsible for absorbing digested nutrients. They have a brush border with microvilli that significantly increases the surface area for absorption.

Golgi: A prominent organelle within the absorptive epithelial cells, the Golgi apparatus plays a key role in processing, packaging, and sorting proteins and lipids. Here, it is involved in combining fatty globules with proteins to form chylomicrons.

Capillary: Tiny blood vessels that are part of the circulatory system, found in the villi of the small intestine. While most nutrients enter the capillaries directly, absorbed lipids primarily enter the lacteals.

Lacteal: A lymphatic capillary located within the villus of the small intestine, specialized for absorbing dietary fats. Unlike other absorbed nutrients that enter the bloodstream directly, chylomicrons containing fats enter the lacteals.

Fatty acids and monoglycerides (resulting from fat digestion leave micelles and enter epithelial cell): After being transported to the brush border by micelles, the fatty acids and monoglycerides diffuse across the cell membrane into the absorptive epithelial cells. This passive process is facilitated by their lipid-soluble nature.

Fatty acids link to form triglycerides: Once inside the absorptive epithelial cells, the absorbed fatty acids and monoglycerides are re-esterified to re-form triglycerides in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. This process effectively traps the lipids within the cell.

Fatty globules combine with proteins to form chylomicrons (inside Golgi apparatus): The newly synthesized triglycerides, along with cholesterol and phospholipids, are then combined with specific proteins within the Golgi apparatus to form large lipoprotein particles called chylomicrons. These proteins stabilize the lipid core and make the particle water-soluble for transport.

Chylomicrons are extruded from the epithelial cell and enter a lacteal (lymph capillary): Once formed, chylomicrons are too large to directly enter the bloodstream capillaries. Instead, they are exocytosed from the basal side of the epithelial cells and pass into the adjacent lacteals.

Lymph in the lacteal transports chylomicrons away from intestine: The lymph fluid within the lacteals collects the chylomicrons and transports them through the lymphatic system. This lymphatic pathway eventually empties into the bloodstream via the thoracic duct, bypassing the hepatic portal system.

The efficient absorption of dietary fats is a testament to the sophistication of the human digestive system. Unlike carbohydrates and proteins, which are directly absorbed into the bloodstream, lipids present unique challenges due to their hydrophobic nature in the predominantly aqueous environment of the gastrointestinal tract. This complex process begins with the mechanical emulsification of large fat globules and culminates in the transport of resynthesized fats via the lymphatic system. Understanding the sequential steps involved in lipid absorption is fundamental to comprehending nutrient delivery and the physiological basis of fat metabolism.

The journey of fat absorption commences in the lumen of the small intestine, where large fat droplets are first emulsified into smaller ones by the action of bile salts, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder. This emulsification significantly increases the surface area for the pancreatic lipase enzyme to act upon, breaking down triglycerides into fatty acids and monoglycerides. These end products, along with bile salts and fat-soluble vitamins, then aggregate to form micelles, which are crucial for their transport.

Micelles, with their hydrophilic exteriors and hydrophobic interiors, effectively ferry the fatty acids and monoglycerides through the aqueous intestinal fluid to the brush border of the absorptive epithelial cells. Upon reaching the cell membrane, the fatty acids and monoglycerides passively diffuse across the membrane and into the cytoplasm of these cells. Inside the epithelial cells, a remarkable transformation occurs:

- Re-esterification: The absorbed fatty acids and monoglycerides are promptly re-esterified to re-form triglycerides within the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. This process prevents the lipids from diffusing back into the lumen.

- Chylomicron Formation: These newly synthesized triglycerides, along with cholesterol and phospholipids, are then encased in a protein coat within the Golgi apparatus, forming lipoprotein particles known as chylomicrons. The protein coat makes the chylomicrons soluble for transport.

Once formed, chylomicrons are too large to enter the conventional bloodstream capillaries directly. Instead, they are exocytosed from the basal aspect of the epithelial cells and enter the lacteals, which are specialized lymphatic capillaries located within the intestinal villi. The lymphatic system then transports these chylomicrons, rich in dietary fats, away from the intestine, eventually delivering them into the systemic circulation via the thoracic duct. This bypasses the hepatic portal system, allowing peripheral tissues to access the absorbed fats first. Disruptions in this pathway, such as deficiencies in bile production or pancreatic lipase, can lead to fat malabsorption, characterized by steatorrhea (fatty stools), and deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins.

In conclusion, the absorption of dietary lipids is a highly specialized and multi-faceted process essential for delivering vital energy and fat-soluble nutrients to the body. From emulsification and micelle formation in the intestinal lumen to re-esterification, chylomicron assembly, and lymphatic transport within the epithelial cells, each step is meticulously orchestrated. A comprehensive understanding of this complex journey is critical for appreciating human physiology, metabolic health, and the clinical implications of lipid malabsorption.