Explore the unique histological features of the large intestine, a crucial segment of the digestive tract expertly adapted for water reabsorption, electrolyte balance, and the formation of feces. This article details the distinctive cellular composition, including abundant goblet cells and deep intestinal glands, and structural elements like lymphatic nodules, highlighting their collective role in maintaining digestive health and forming a protective barrier.

Large intestine: This is the terminal section of the gastrointestinal tract, primarily tasked with absorbing water and electrolytes, solidifying waste, and housing a diverse microbiota. Its internal structure is distinctly tailored to these specific functions, setting it apart from other digestive organs.

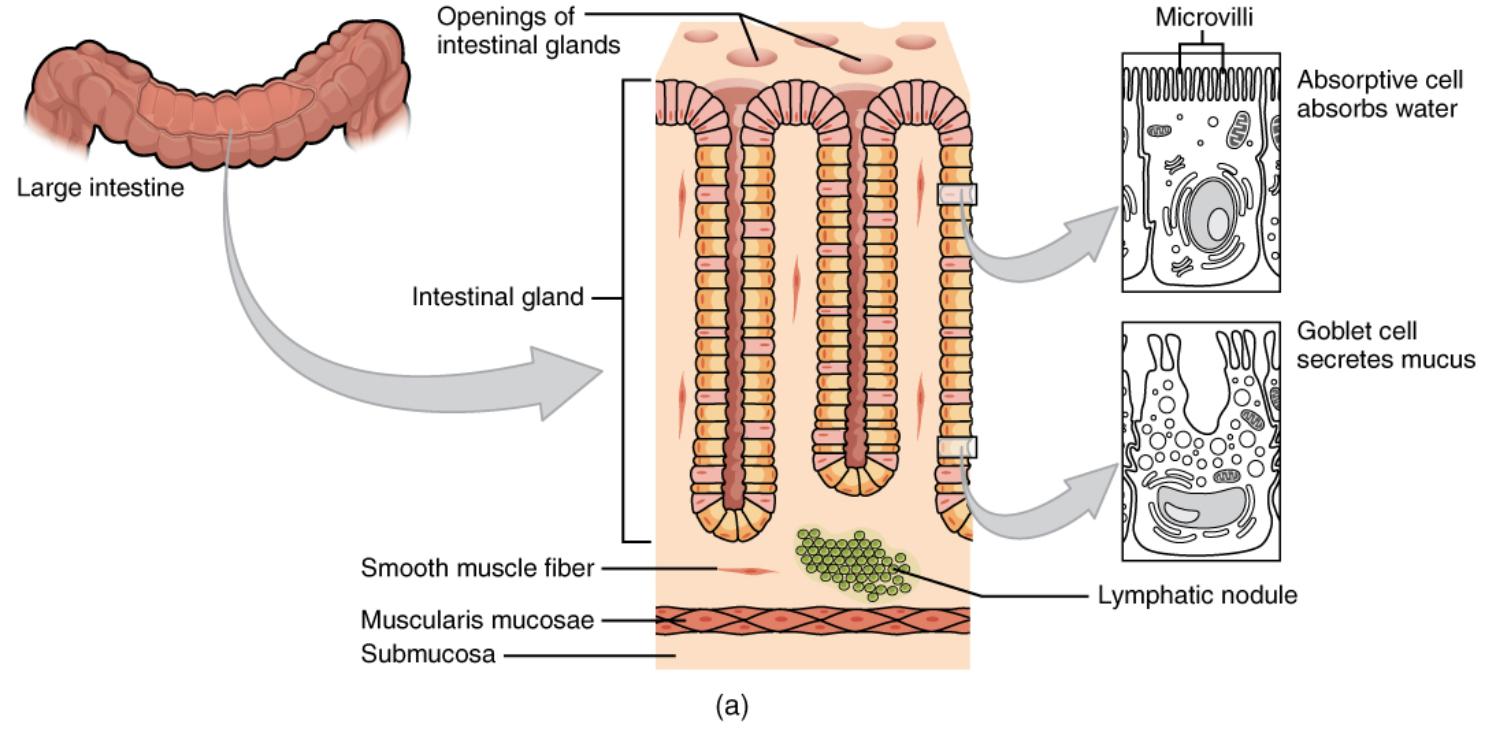

Openings of intestinal glands: These are the entry points on the luminal surface that lead into the crypts of Lieberkühn, which are deep invaginations of the intestinal lining. They facilitate the delivery of mucus and other secretions to the intestinal lumen and allow for continuous epithelial cell renewal.

Intestinal gland: Also known as crypts of Lieberkühn, these are tubular glands extending deep into the large intestinal mucosa. They are vital for producing mucus, regenerating epithelial cells from stem cells, and maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier against pathogens.

Microvilli: These are minute, finger-like projections found on the apical surface of absorptive cells, forming a brush border. While less dense than in the small intestine, they still contribute to the surface area for efficient reabsorption of water and electrolytes.

Absorptive cell absorbs water: These columnar epithelial cells are the predominant cell type lining the large intestine. Their primary function is the reabsorption of water and electrolytes from the indigestible chyme, a critical process for concentrating fecal matter and preventing dehydration.

Goblet cell secretes mucus: These specialized glandular cells are highly abundant throughout the large intestinal epithelium. They produce and secrete large quantities of mucus, which lubricates the passage of developing feces, protecting the delicate intestinal lining from mechanical damage and chemical irritation.

Smooth muscle fiber: These individual contractile cells are components of the muscular layers of the large intestine, particularly the muscularis mucosae and muscularis externa. Their coordinated contractions are responsible for the mixing (segmentation) and propulsive (peristaltic) movements of fecal material.

Lymphatic nodule: These are discrete clusters of lymphoid tissue found within the lamina propria and submucosa of the large intestine. They represent a key part of the gut’s immune system, housing immune cells that survey for pathogens and initiate protective responses against microbial threats.

Muscularis mucosae: This is a thin layer of smooth muscle situated at the base of the mucosa, directly beneath the intestinal glands. Its contractions contribute to local movements of the mucosa, which can aid in the expulsion of glandular secretions and enhance contact with luminal contents.

Submucosa: This connective tissue layer lies beneath the muscularis mucosae and is composed of dense irregular connective tissue. It contains larger blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerve plexuses, providing essential structural support, nutrient supply, and innervation to the overlying mucosa.

The large intestine, though often considered the final stage of digestion, is a highly specialized organ with a distinctive histological architecture. Unlike the small intestine, which focuses on nutrient absorption, the large intestine is expertly adapted for the crucial tasks of reabsorbing water and electrolytes, forming solid feces, and harboring a vast and complex microbiota essential for gut health. Its unique microscopic features are tailored to these specific roles, providing an efficient system for waste management and internal environmental balance.

The inner lining, or mucosa, of the large intestine lacks the prominent villi seen in the small intestine, reflecting its different functional priorities. Instead, it is characterized by deep, straight tubular structures known as intestinal glands or crypts of Lieberkühn. These crypts are densely populated with a specific array of cells that perform vital functions, from lubrication to immune defense. This cellular composition is critical for creating a protective barrier and facilitating the transformation of liquid chyme into well-formed stool.

Understanding the histology of the large intestine is paramount for appreciating its contribution to overall physiological well-being. The intricate arrangement of its cells and tissues underscores its dual role in processing indigestible material and safeguarding the body from the challenges presented by a high bacterial load. The accompanying diagram visually dissects these key histological features, illustrating how each component plays a part in the large intestine’s specialized functions.

The Specialized Cellular Landscape of the Large Intestine

The large intestine’s mucosa is a testament to functional specialization, primarily composed of absorptive cells and an exceptionally high density of goblet cells, along with a significant immune component.

- Absorptive Cells: These columnar epithelial cells are the predominant cell type lining the large intestine. While they possess microvilli, these are generally shorter and less numerous than those found in the small intestine. Their main function is the efficient reabsorption of water and electrolytes, such as sodium and chloride ions, from the luminal contents. This process is crucial for preventing dehydration and compacting the chyme into solid feces.

- Goblet Cells: A hallmark of the large intestinal epithelium is the extraordinary abundance of goblet cells. These unicellular glands are interspersed throughout the intestinal glands and on the surface epithelium. Their primary role is the continuous production and secretion of large quantities of mucus. This thick, alkaline mucus serves several vital protective functions:

- Lubrication: It lubricates the passage of fecal matter, reducing friction as it moves through the colon.

- Protection: It forms a protective barrier over the epithelium, shielding it from the mechanical abrasion of hardened feces and the chemical irritation from bacterial metabolites.

- Bacterial Adherence: The mucus layer also provides a matrix that helps maintain the beneficial gut microbiota while preventing direct adherence of pathogens to the epithelial cells.

- Intestinal Glands (Crypts of Lieberkühn): These deep, straight tubular glands are characteristic of the large intestine. In addition to absorptive and goblet cells, these crypts contain stem cells at their base, which continuously proliferate and differentiate to replace the mature epithelial cells, ensuring the constant renewal and integrity of the intestinal lining.

- Lymphatic Nodules: Situated primarily within the lamina propria and often extending into the submucosa, lymphatic nodules are prominent features. These immune aggregates contain various immune cells, including lymphocytes and macrophages, and are crucial for the local immune surveillance of the intestinal environment. They play a significant role in defending against potential pathogens that reside within the large intestine’s rich microbial ecosystem.

Supporting Layers: Muscularis Mucosae and Submucosa

Beneath the epithelial layer, the muscularis mucosae is a thin band of smooth muscle that facilitates local movements of the mucosa, contributing to the expulsion of secretions from the intestinal glands. The submucosa, a layer of connective tissue, provides structural support and contains the network of blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves that nourish and regulate the activity of the overlying mucosa.

In conclusion, the histology of the large intestine is a masterpiece of biological adaptation, perfectly engineered for its unique digestive and protective roles. The absence of villi, coupled with the prevalence of deep, mucus-secreting intestinal glands and a robust immune presence, underscores its specialization in water reabsorption, waste solidification, and defense against pathogens. This intricate microscopic organization is fundamental to maintaining fluid balance, ensuring efficient waste elimination, and safeguarding the overall health of the gastrointestinal tract.