Explore the intricate world of digestive enzymes and hormones, crucial for breaking down food and absorbing nutrients. This article delves into the functions of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and pancreas, detailing how specialized cells contribute to this vital process.

Esophagus: The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx (throat) to the stomach, acting as a conduit for swallowed food. Through a process called peristalsis, rhythmic muscle contractions propel food downward, preventing reflux and ensuring efficient transport.

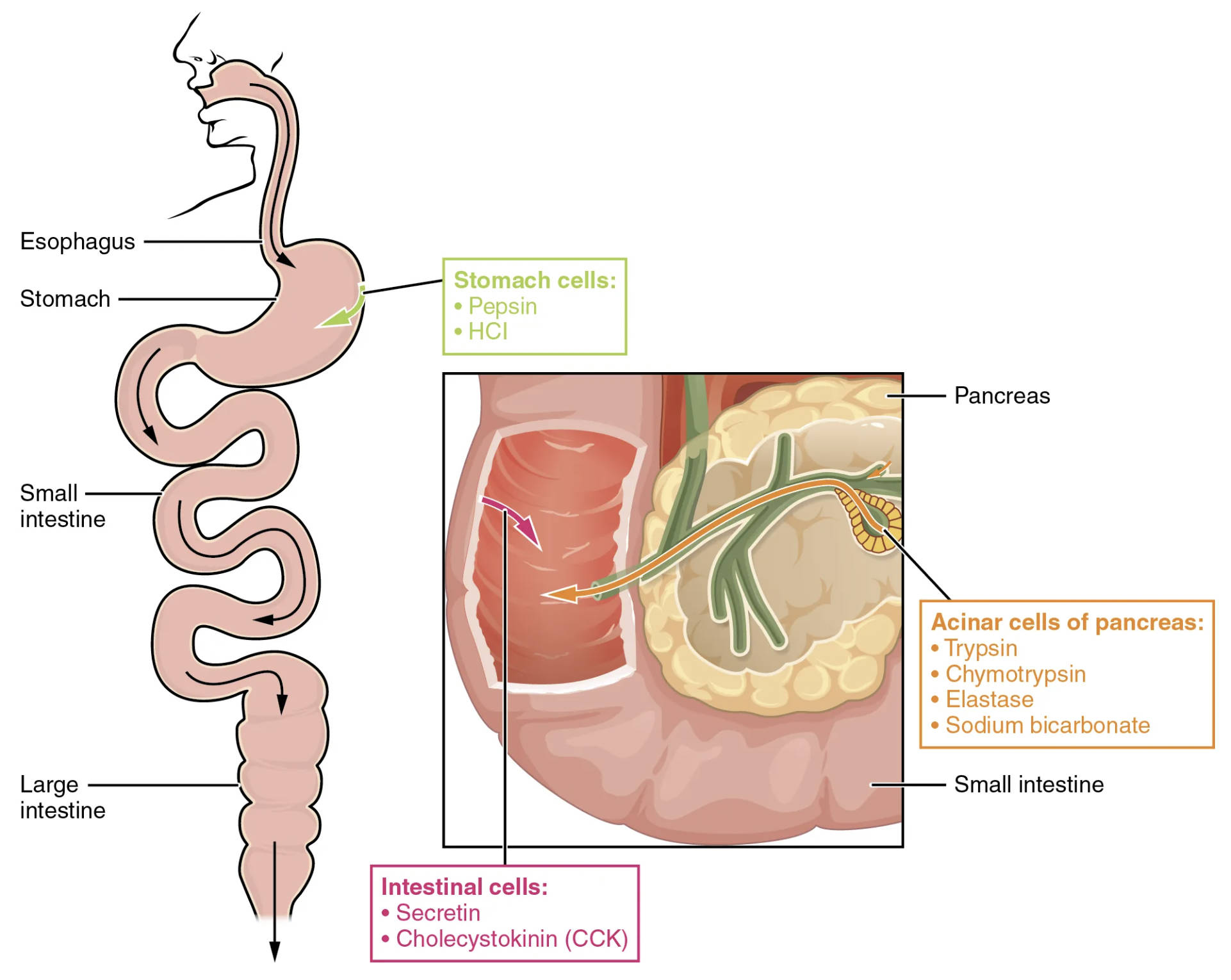

Stomach: The stomach is a J-shaped muscular organ located in the upper abdomen, responsible for the initial breakdown of food, particularly proteins. It churns food with gastric juices, forming a semi-liquid mixture called chyme.

Small intestine: The small intestine is a long, coiled tube extending from the stomach to the large intestine, where most chemical digestion and nutrient absorption occur. Its inner surface is lined with villi and microvilli, vastly increasing its surface area for efficient absorption.

Large intestine: The large intestine is the final section of the gastrointestinal tract, primarily responsible for absorbing water and electrolytes from indigestible food matter. It also houses a diverse microbiome that aids in the fermentation of remaining food particles and the synthesis of certain vitamins.

Stomach cells: Pepsin: Pepsin is a powerful proteolytic enzyme secreted by chief cells in the stomach lining, active in the acidic environment of the stomach. It initiates the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides.

Stomach cells: HCl: Hydrochloric acid (HCl) is produced by parietal cells in the stomach, creating a highly acidic environment (pH 1.5-3.5) essential for several digestive functions. It denatures proteins, making them more accessible to pepsin, and also kills most bacteria ingested with food.

Pancreas: The pancreas is a glandular organ located behind the stomach, playing a dual role in digestion and hormone production. It secretes digestive enzymes into the small intestine and hormones like insulin and glucagon into the bloodstream.

Acinar cells of pancreas: Trypsin: Trypsin is a potent proteolytic enzyme secreted by the pancreatic acinar cells as an inactive precursor, trypsinogen. Once activated in the small intestine, it breaks down proteins into smaller peptides, working in conjunction with other proteases.

Acinar cells of pancreas: Chymotrypsin: Chymotrypsin is another crucial proteolytic enzyme produced by the pancreas, also secreted as an inactive zymogen, chymotrypsinogen. It specifically targets peptide bonds adjacent to certain amino acids, further breaking down proteins.

Acinar cells of pancreas: Elastase: Elastase is a pancreatic enzyme that primarily degrades elastin, a fibrous protein found in connective tissues. This enzyme contributes to the thorough digestion of proteins in the diet.

Acinar cells of pancreas: Sodium bicarbonate: Sodium bicarbonate is secreted by the pancreatic duct cells into the small intestine, acting as a vital buffer. It neutralizes the acidic chyme entering from the stomach, creating an optimal pH environment for pancreatic and intestinal enzymes to function effectively.

Small intestine: The small intestine is the primary site for the absorption of nutrients, including amino acids, carbohydrates, and fats. Its extensive surface area, enhanced by villi and microvilli, maximizes the efficiency of nutrient uptake into the bloodstream.

Intestinal cells: Secretin: Secretin is a hormone released by S cells in the duodenum in response to acidic chyme entering the small intestine. It stimulates the pancreas to secrete bicarbonate-rich fluid, neutralizing stomach acid.

Intestinal cells: Cholecystokinin (CCK): Cholecystokinin (CCK) is a hormone secreted by I cells in the duodenum and jejunum in response to fats and proteins in the chyme. It stimulates the gallbladder to contract and release bile, and the pancreas to secrete digestive enzymes.

The human digestive system is a remarkably efficient and complex network of organs, working in concert to process food, extract nutrients, and eliminate waste. From the moment food enters the mouth until waste exits the body, a symphony of mechanical and chemical processes unfolds. This intricate system relies heavily on a diverse array of digestive enzymes and regulatory hormones, which act as catalysts and messengers to ensure smooth and effective digestion. Understanding the roles of these specialized biological molecules is key to appreciating the sophistication of our internal machinery and maintaining overall health.

At the core of digestion lies the crucial task of breaking down large food molecules into smaller, absorbable units. Proteins, carbohydrates, and fats, in their complex forms, cannot be directly absorbed by the body. This is where enzymes become indispensable. Secreted by various organs such as the salivary glands, stomach, pancreas, and small intestine, these biological catalysts accelerate chemical reactions, systematically dismantling food components. Concurrently, hormones, acting as chemical messengers, regulate the timing and intensity of digestive processes, ensuring that each stage proceeds optimally.

The journey of food through the digestive tract is a carefully orchestrated sequence of events, beginning in the mouth and progressing through the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. Each organ contributes uniquely to the digestive process. For instance, the stomach initiates protein digestion with its acidic environment and the enzyme pepsin. The small intestine, however, is where the bulk of chemical digestion and nutrient absorption takes place, with significant contributions from pancreatic enzymes and bile from the liver. The coordinated action of these organs, driven by enzymes and hormones, exemplifies the body’s physiological precision.

- Enzymes are protein catalysts that speed up chemical reactions without being consumed.

- Hormones are chemical messengers that regulate physiological processes.

- The stomach primarily handles protein digestion.

- The small intestine is the main site for nutrient absorption.

The stomach plays a pivotal role in the initial stages of protein digestion. Its specialized cells produce hydrochloric acid (HCl) and pepsin. HCl not only denatures proteins, unfolding their complex structures to make them more accessible for enzymatic breakdown, but also activates pepsinogen into its active form, pepsin. Pepsin then begins to cleave proteins into smaller polypeptides. This highly acidic environment is crucial for killing most microorganisms ingested with food, providing a protective barrier against potential pathogens. The stomach’s muscular contractions further aid in mechanical digestion, mixing food with gastric juices to form chyme.

As the chyme, a semi-liquid mixture, moves from the stomach into the small intestine, the digestive process becomes even more complex and refined. Here, the pancreas becomes a key player, releasing a potent cocktail of digestive enzymes and sodium bicarbonate into the duodenum. Pancreatic enzymes, such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, and elastase, continue the breakdown of proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. Simultaneously, pancreatic lipase digests fats, and pancreatic amylase breaks down carbohydrates. The sodium bicarbonate secreted by the pancreas neutralizes the acidic chyme, creating an alkaline environment essential for these pancreatic and intestinal enzymes to function effectively.

Beyond enzymatic action, the small intestine itself produces vital hormones that regulate the digestive process. Secretin, released in response to acidic chyme, stimulates the pancreas to release bicarbonate. Cholecystokinin (CCK), secreted in response to fats and proteins, triggers the release of bile from the gallbladder to emulsify fats and stimulates the pancreas to release its digestive enzymes. This intricate hormonal feedback loop ensures that digestive secretions are precisely matched to the incoming food, optimizing efficiency and nutrient absorption. The final breakdown of carbohydrates and peptides into their simplest forms, such as glucose and amino acids, occurs at the brush border of the intestinal cells, ready for absorption into the bloodstream.

In conclusion, the sophisticated interplay of digestive enzymes and hormones is absolutely essential for the breakdown of food and the subsequent absorption of vital nutrients. From the powerful acidic environment of the stomach, initiating protein digestion with pepsin and HCl, to the precise enzymatic and hormonal regulation within the small intestine and pancreas, every component of the gastrointestinal system works in perfect synchrony. This intricate orchestration ensures that our bodies can effectively extract the energy and building blocks needed for growth, repair, and overall health.