The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) serves as the primary manufacturing and logistics hub within the eukaryotic cell, coordinating the production of essential proteins and lipids. By examining the relationship between the rough endoplasmic reticulum, the nucleolus, and neighboring mitochondria, we can appreciate the complex physiological dance required to maintain cellular health and systemic homeostasis.

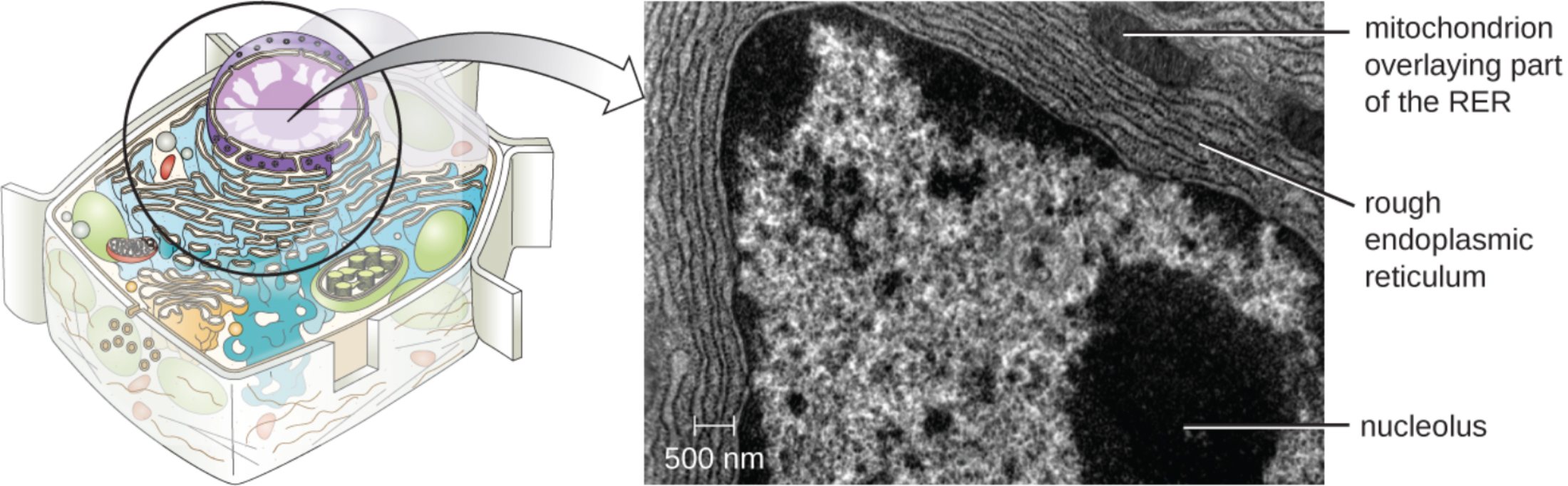

mitochondrion overlaying part of the RER: This label identifies a double-membrane organelle responsible for generating the chemical energy required for cellular processes. Its proximity to the protein-manufacturing machinery ensures that the high metabolic cost of synthesis is met by a constant supply of energy.

rough endoplasmic reticulum: Characterized by a surface studded with ribosomes, this membranous network is the site of active protein synthesis. It facilitates the folding and quality control of proteins that are destined for secretion or integration into the plasma membrane.

nucleolus: This dense, non-membrane-bound structure within the nucleus is the site of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) synthesis. The subunits produced here are essential for forming the ribosomes that eventually populate the surface of the rough endoplasmic reticulum.

500 nm: This scale bar provides a precise measurement of the magnification used in the transmission electron micrograph. It allows scientists to calculate the actual dimensions of the cellular organelles and observe the intricate details of their internal membranes.

The Microscopic Factory Floor of the Eukaryotic Cell

The cell is often likened to a bustling city, with the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) acting as its major manufacturing plant. The RER is a continuous network of flattened sacs known as cisternae, which are physically linked to the nuclear envelope. This arrangement allows for the efficient transfer of genetic instructions from the nucleus to the factory floor, where those instructions are translated into functional molecular structures.

The “rough” appearance of this organelle is due to the presence of millions of ribosomes attached to its exterior surface. These ribosomes are not permanent fixtures; they bind to the RER membrane only when they begin to synthesize a protein containing a specific signal sequence. This targeted approach ensures that the cell can distinguish between proteins meant for the cytoplasm and those that need to be sequestered within the endomembrane system for specialized processing.

The functional integrity of the RER is supported by several key physiological roles:

- Synthesis of lysosomal enzymes and secreted proteins like insulin.

- Production of the integral membrane proteins that form the cell’s outer barrier.

- N-linked glycosylation, which involves adding carbohydrate chains to newly formed proteins.

- Protein folding and quality control to prevent the export of malformed molecules.

Maintaining this factory requires a tremendous amount of resources. The nucleolus must constantly produce ribosomal subunits to replace those that wear out, while the mitochondria must provide a steady stream of adenosine triphosphate to power the mechanical movement of molecules across membranes. This interconnectedness highlights the fact that no single organelle functions in isolation; rather, they exist in a state of constant, synchronized cooperation.

Physiological Mechanisms of Protein Processing and Transport

The primary physiological mission of the rough endoplasmic reticulum is the synthesis of proteins destined for the secretory pathway. As a ribosome begins the process of translation, a specialized molecule called a signal recognition particle binds to the emerging peptide, pausing the process and directing the complex to the RER membrane. Once docked, the ribosome continues its work, threading the growing protein chain directly into the internal space, or lumen, of the ER.

Inside the lumen, the environment is highly regulated to promote proper folding. Chaperone proteins assist in the complex structural arrangements of the polypeptide chains, ensuring they achieve their correct three-dimensional shapes. If a protein fails to fold correctly, it is often targeted for degradation, a process that prevents the accumulation of toxic, misfolded proteins that could lead to cellular dysfunction or disease.

Beyond simple synthesis, the RER is heavily involved in post-translational modifications. Enzymes within the cisternae add specific chemical groups to the proteins, such as sugars or lipids, which act as molecular “zip codes” to direct the protein to its final destination. For example, proteins meant for the Golgi apparatus are packaged into small transport vesicles that bud off from the RER membrane and travel along the cytoskeleton.

The structural relationship visible in electron micrographs, where the RER often wraps around the nucleus or sits adjacent to mitochondria, is a testament to the efficiency of biological design. By minimizing the distance between the energy source, the instruction center, and the manufacturing site, the cell optimizes its metabolic output. This intricate level of organization is fundamental to the health of all tissues in the human body, from the antibody-producing cells of the immune system to the hormone-secreting cells of the endocrine glands.

In summary, the rough endoplasmic reticulum is a dynamic and essential component of the cellular landscape. Its role in protein synthesis, folding, and transport is supported by the energy of the mitochondria and the biosynthetic output of the nucleolus. By understanding these microscopic interactions, we gain a clearer picture of the foundational processes that support life and the remarkable precision with which our cells operate on a daily basis.