The peritoneum, a complex serous membrane lining the abdominal cavity, forms specialized folds that play crucial roles in supporting and organizing abdominal organs. These peritoneal folds not only anchor organs in place but also provide pathways for blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic tissue. This article delves into the five major peritoneal folds, explaining their anatomical positions and critical functions in maintaining abdominal stability and facilitating organ function.

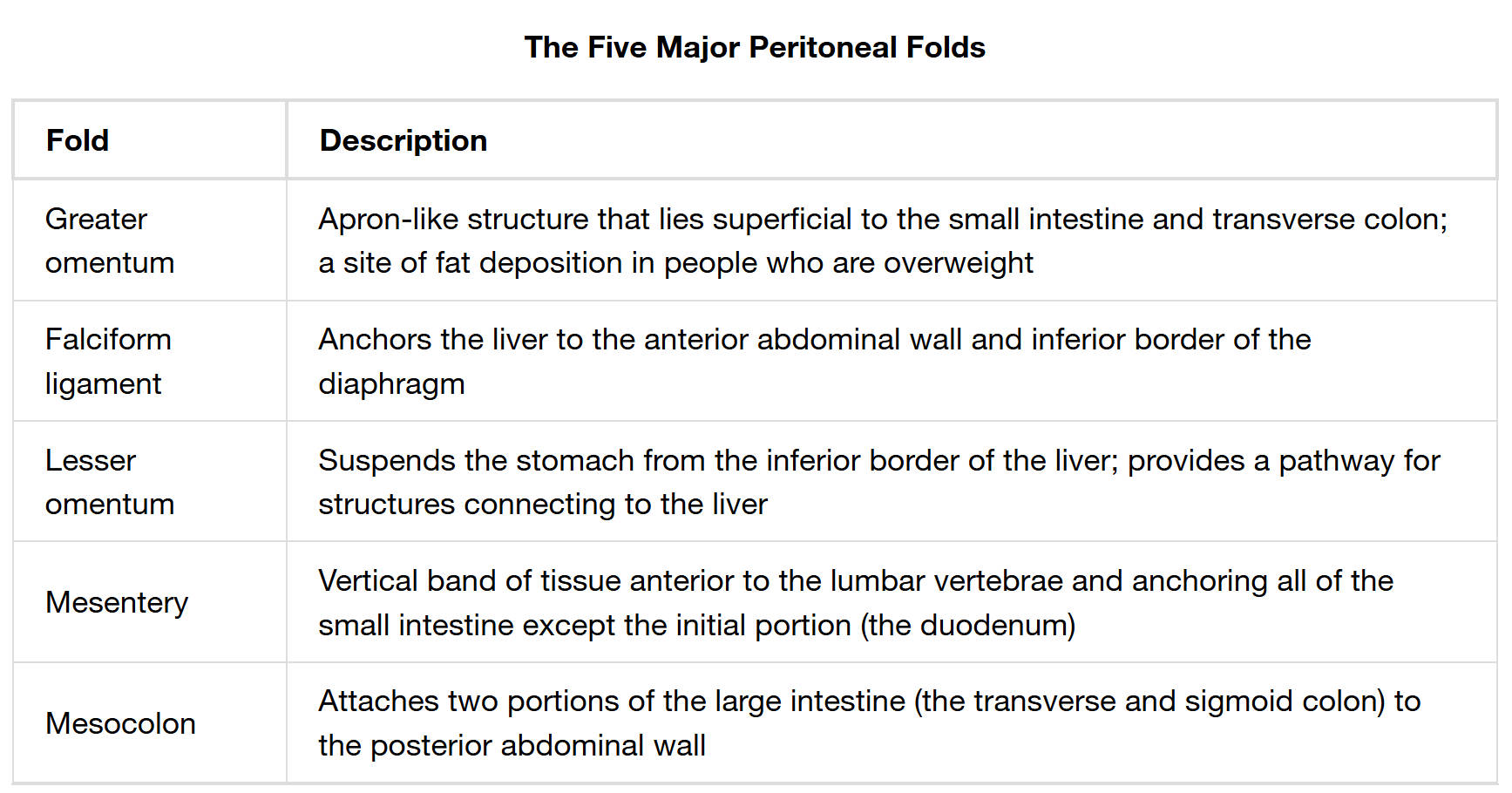

Fold: This column lists the specific names of the five major peritoneal folds being discussed. Each fold represents a unique double layer of peritoneum that provides structural support and serves specific functional roles within the abdominal cavity. Understanding the individual names is the first step in comprehending their distinct contributions.

Description: This column provides a detailed explanation of each peritoneal fold, outlining its anatomical location, structural characteristics, and primary functions. These descriptions highlight how each fold anchors organs, provides pathways for neurovascular bundles, or serves as a site for fat deposition. The functional significance of these folds is crucial for abdominal organ health and stability.

The abdominal cavity is a marvel of anatomical organization, where vital organs are not only housed but also precisely positioned and supported. This intricate arrangement is largely attributed to the peritoneum, a vast serous membrane that lines the cavity and forms specialized structures known as peritoneal folds. These folds are essentially double layers of peritoneum that extend from the abdominal wall to encapsulate or suspend various organs. They are indispensable for maintaining the spatial relationships of abdominal viscera, preventing entanglement, and providing crucial pathways for neurovascular and lymphatic supply.

The major peritoneal folds serve a multitude of functions, including:

- Anchoring organs: Providing stability and preventing displacement.

- Facilitating organ movement: Allowing organs to glide smoothly against each other.

- Housing neurovascular bundles: Protecting and delivering blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels to organs.

- Fat storage: Serving as a site for energy reserves.

A detailed understanding of these specific folds—the greater omentum, falciform ligament, lesser omentum, mesentery, and mesocolon—is essential for comprehending abdominal anatomy, surgical considerations, and the potential spread of disease within the abdominal cavity. Each fold possesses unique characteristics and plays a distinct, yet interconnected, role in the overall function and health of the digestive system and associated organs.

The Greater Omentum: The Abdominal Apron

The greater omentum is a remarkable, apron-like peritoneal fold that drapes over the anterior surface of the small intestine and transverse colon. Often referred to as the “abdominal policeman” due to its ability to migrate to sites of inflammation and infection, it is a significant site of fat deposition, particularly in individuals who are overweight. This fatty tissue not only provides insulation but also contains numerous macrophages and immune cells, playing a crucial role in abdominal immune defense. Its flexibility allows it to wrap around inflamed areas, potentially walling off infections and preventing their spread throughout the peritoneal cavity.

The Falciform Ligament: Anchoring the Liver

The falciform ligament is a crescent-shaped peritoneal fold that serves to anchor the liver firmly in place. It attaches the liver to the anterior abdominal wall and extends superiorly to the inferior border of the diaphragm. This ligament divides the liver into its anatomical right and left lobes on its anterior surface. While primarily an anchoring structure, it is also a remnant of the ventral mesentery and contains the round ligament of the liver (ligamentum teres hepatis), which is the obliterated umbilical vein from fetal circulation. Its robust attachment ensures the liver remains stable despite movements of the torso and diaphragm.

The Lesser Omentum: Suspending the Stomach and Connecting to the Liver

The lesser omentum is a peritoneal fold that extends from the inferior border of the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach and the initial part of the duodenum. It acts as a suspensory ligament for the stomach, holding it in proximity to the liver. More significantly, the lesser omentum provides a critical pathway for essential structures connecting to the liver, including the hepatic portal vein, hepatic artery proper, and common bile duct, collectively known as the portal triad. These structures are vital for the liver’s function in processing nutrients, detoxifying blood, and producing bile. The lesser omentum also contains lymphatics and nerves, further illustrating its role as a conduit.

The Mesentery and Mesocolon: Organizing the Intestines

The mesentery is a fan-shaped, vertical band of tissue that attaches all of the small intestine, with the exception of the initial portion (the duodenum), to the posterior abdominal wall. This extensive fold not only anchors the convoluted loops of the jejunum and ileum but also provides a conduit for their blood supply, lymphatic drainage, and innervation. The mesentery’s structural integrity is crucial for preventing the entanglement of the intestines and ensuring their mobility for efficient peristalsis. Similarly, the mesocolon refers to peritoneal folds that attach two specific portions of the large intestine—the transverse colon and the sigmoid colon—to the posterior abdominal wall. Like the mesentery, the mesocolon provides vascular and nervous supply, supporting the function and position of these segments of the large intestine.

In conclusion, the five major peritoneal folds—the greater omentum, falciform ligament, lesser omentum, mesentery, and mesocolon—are indispensable anatomical structures within the abdominal cavity. They perform critical roles in supporting, organizing, and stabilizing vital organs, while simultaneously serving as conduits for neurovascular and lymphatic systems. Understanding the unique characteristics and functions of these folds is not only fundamental to comprehending abdominal anatomy but also essential for clinical diagnosis, surgical interventions, and appreciating the intricate orchestration of the human body. These peritoneal structures exemplify the complex yet efficient design that ensures the optimal functioning of our internal systems.