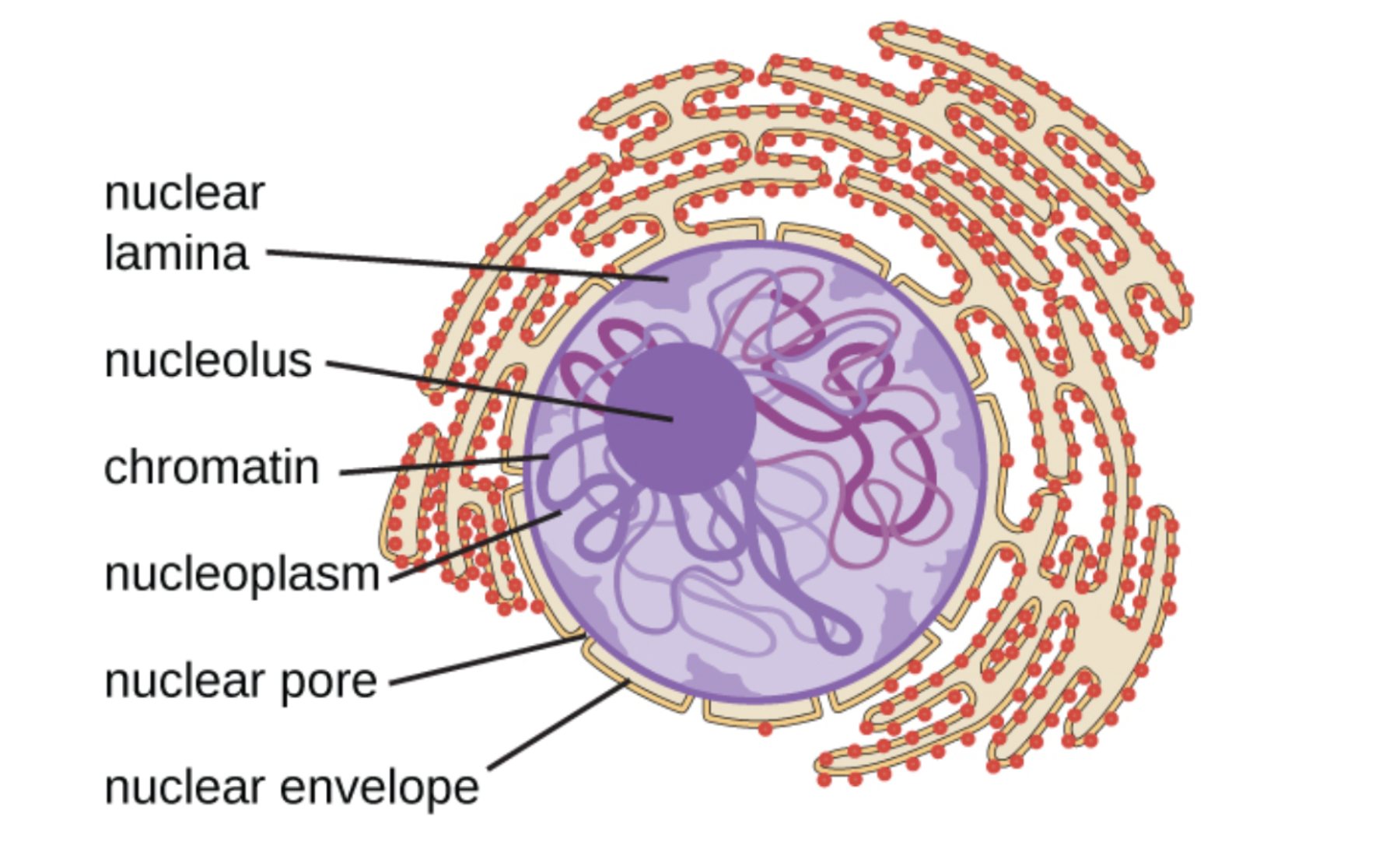

The nucleus serves as the epicenter of cellular function, acting as the protective vault for an organism’s genetic code. Within this intricate structure, the nucleolus plays a vital role in synthesizing the components needed for protein production, effectively serving as the cell’s ribosome factory. By exploring the anatomical features of the nuclear envelope, chromatin, and nuclear pores, we can better understand the physiological processes that drive health and biological development at the microscopic level.

nuclear lamina: This is a dense fibrillar network located on the inner surface of the nuclear envelope composed of intermediate filaments and membrane-associated proteins. It provides essential mechanical support to the nucleus and plays a critical role in organizing chromatin and regulating DNA replication during the cell cycle.

nucleolus: Represented as a dark, dense area within the nucleus, this region is a non-membrane-bound structure that disappears during cell division. It serves as the primary site for ribosomal RNA synthesis and the intricate assembly of preribosomal subunits.

chromatin: This material consists of a complex of DNA and histone proteins that make up the chromosomes in eukaryotic organisms. It functions to efficiently pack the genetic material into the small volume of the nucleus while also controlling the accessibility of DNA for transcription and replication.

nucleoplasm: Often referred to as nuclear sap or karyoplasm, this is the semi-fluid substance that fills the interior of the nucleus. It serves as a medium that suspends various structures like the nucleolus and chromatin, facilitating the diffusion of nucleotides and enzymes necessary for genetic processes.

nuclear pore: These are large protein complexes that span the nuclear envelope, creating channels between the nucleoplasm and the cytoplasm. They act as selective gatekeepers, regulating the transport of macromolecules such as proteins and RNA in and out of the nucleus to maintain cellular homeostasis.

nuclear envelope: This is a double-membrane structure that encapsulates the entire nucleus, separating the genetic material from the surrounding cytoplasm. The inner and outer membranes work together to maintain the integrity of the nuclear environment and serve as an attachment site for the cytoskeleton.

In the complex world of eukaryotic cells, the nucleus stands as the command center, housing the vast majority of an organism’s genetic material. Within this sphere, various specialized components work in harmony to ensure that cellular instructions are correctly interpreted and executed. This anatomical organization is crucial for maintaining life, as even slight disruptions in nuclear structure can lead to significant physiological consequences.

At the very heart of the nucleus lies the nucleolus, a distinct and non-membrane-bound structure that appears as a dense spot under a microscope. Its primary physiological duty is the massive production of the building blocks required for protein synthesis. By orchestrating the assembly of ribosomes, the nucleolus ensures the cell has the machinery necessary to translate genetic code into functional proteins.

The following list summarizes the primary responsibilities of the nuclear components:

- Storage and protection of chromosomal DNA from cytoplasmic enzymes.

- Selective regulation of molecular traffic between the nucleus and cytoplasm via pore complexes.

- Synthesis and processing of ribosomal RNA within the dense nucleolar region.

- Structural support and spatial organization of the genome through the nuclear lamina.

The structural complexity of the nucleus is not merely for protection; it is a dynamic landscape that changes according to the cell’s metabolic needs. During different phases of the cell cycle, the nucleolus and chromatin undergo significant transformations to accommodate DNA replication and cell division. Understanding these microscopic structures is fundamental to grasping how our bodies function at a molecular level and how genetic information translates into physical life.

The Physiology of Ribosomal Assembly

The nucleolus is far more than a simple “spot” inside the nucleus; it is a highly active biochemical hub. Within its borders, specific segments of DNA known as nucleolar organizer regions (NORs) contain the instructions for creating ribosomal RNA (rRNA). Once synthesized, this RNA is folded and combined with proteins that have been imported from the cytoplasm. This process is a marvel of biological engineering, requiring the precise coordination of hundreds of different molecules to create the subunits that will eventually form functional ribosomes.

The density of the nucleolus is a direct reflection of its metabolic activity. In cells that are rapidly growing or secreting large amounts of protein—such as pancreatic cells or developing embryos—the nucleolus is often significantly larger and more prominent. This physiological scaling allows the cell to keep up with the high demand for protein synthesis, highlighting the nucleolus as a barometer for a cell’s overall activity level.

Structural Integrity and Communication

Enclosing this genetic treasury is the nuclear envelope, a sophisticated barrier that provides both protection and a means of communication. The presence of the nuclear lamina on the interior provides a rigid framework, ensuring the nucleus maintains its spherical or oval shape even under mechanical stress. This structural support is vital because the organization of chromatin is largely dependent on its attachment to the lamina; when this attachment is faulty, it can lead to severe issues in gene expression and cellular aging.

Communication between the internal nuclear environment and the rest of the cell is managed by the nuclear pores. These are not simple holes but complex molecular sieves. They recognize specific “passports” or signal sequences on proteins, allowing necessary transcription factors to enter the nucleus while permitting finished mRNA strands to exit. This selective permeability ensures that the delicate processes of DNA replication and RNA transcription occur in a stable, controlled environment, shielded from the metabolic “noise” of the cytoplasm.

The Role of Chromatin and Nucleoplasm

Suspended within the nucleoplasm, chromatin exists in two main forms: euchromatin and heterochromatin. Euchromatin is less densely packed, representing regions of DNA that are actively being read and used by the cell. Heterochromatin is tightly coiled and generally inactive, serving as a way to “silence” genes that are not currently needed. This spatial arrangement is constantly shifting, allowing the cell to adapt its genetic output in response to hormones, nutrients, or environmental changes.

The nucleoplasm itself facilitates these movements. As a fluid medium, it allows for the rapid diffusion of the raw materials needed for life, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and free nucleotides. Without this specialized environment, the enzymes responsible for repairing damaged DNA or copying genetic instructions would be unable to reach their targets. Thus, the entire nuclear apparatus functions as a highly integrated system, where every structure from the outer envelope to the innermost nucleolus plays a part in the continuity of life.

The intricate design of the nucleus and its sub-components reflects millions of years of evolutionary refinement. From the mechanical strength provided by the lamina to the manufacturing prowess of the nucleolus, every part serves a purpose that is fundamental to human health. By appreciating the complexity of these microscopic structures, we gain a deeper insight into the foundational mechanisms of genetics, protein synthesis, and the very essence of cellular life.