The Golgi apparatus is a vital organelle within the eukaryotic endomembrane system, acting as the primary hub for modifying, sorting, and packaging macromolecules for secretion or delivery to other organelles. Discovered in 1898 by Camillo Golgi, this complex arrangement of flattened membrane sacs is essential for the production of functional glycoproteins and glycolipids. By facilitating intricate biochemical modifications, the Golgi apparatus ensures that the cell’s proteins and lipids are accurately directed to their final destinations, maintaining the overall health and functionality of the human body.

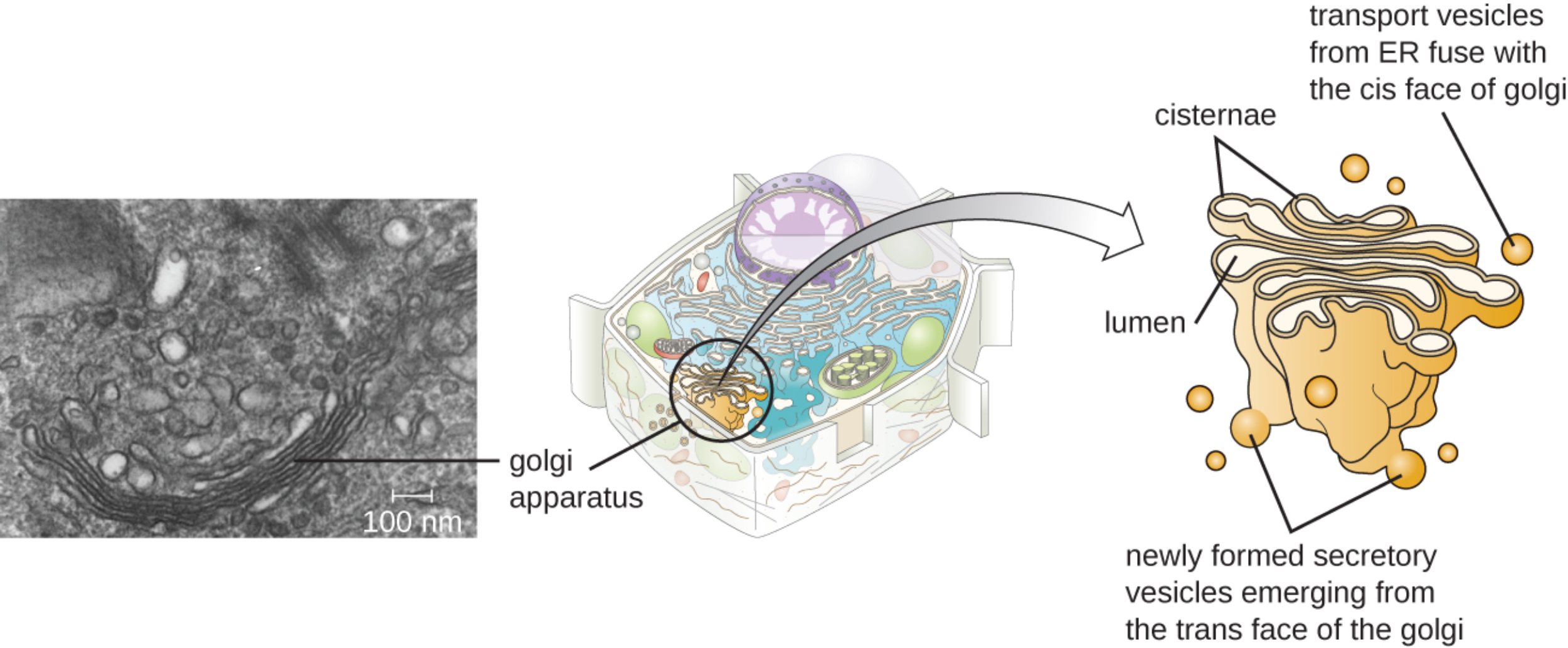

golgi apparatus: This organelle consists of a series of flattened, membrane-bound sacs that function as the processing center of the cell. It plays a central role in the endomembrane system by modifying and packaging proteins and lipids synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum.

cisternae: These are the individual, stacked membrane disks that provide the structural framework for the Golgi complex. Each cisterna contains unique enzymes that facilitate specific chemical reactions as molecules move through the stack.

lumen: The lumen is the internal space or cavity enclosed within each of the Golgi cisternae. This specialized environment allows for controlled biochemical processes, such as the modification of carbohydrate chains, to occur away from the cytoplasm.

transport vesicles from ER fuse with the cis face of golgi: These small, spherical structures carry newly synthesized proteins and lipids from the endoplasmic reticulum to the receiving side of the Golgi. Upon arrival, they merge with the cis face membrane to release their cargo into the lumen for processing.

newly formed secretory vesicles emerging from the trans face of the golgi: These vesicles bud off from the exit side of the organelle once the molecules have been fully modified and sorted. They are responsible for transporting finished products, such as enzymes or hormones, to the plasma membrane or other intracellular targets.

The Central Role of the Golgi Apparatus in Cellular Biology

The Golgi apparatus serves as the “post office” of the cell, where molecular products are received, refined, and addressed for delivery. It is an integral part of the cellular machinery that manages the flow of materials through the secretory pathway. Without the Golgi, proteins would remain in their immature states, unable to perform the complex tasks required for life, such as cell signaling or structural support.

Historically, the identification of this organelle marked a major milestone in cytology. Italian scientist Camillo Golgi used a specialized silver nitrate staining technique to visualize these structures within the cells of Plasmodium, the parasite responsible for malaria. This discovery revealed a level of internal organization within the cell that had previously been invisible to researchers, highlighting the importance of membrane-bound organelles in compartmentalizing biological functions.

The functionality of the Golgi apparatus is characterized by its distinct polarity, transitioning from the “cis” face (entry) to the “trans” face (exit). This directional flow ensures that molecules undergo a sequential series of modifications as they pass through different cisternae. Key activities performed within this organelle include:

- The addition or removal of sugar moieties through glycosylation to create glycoproteins.

- The synthesis of complex polysaccharides for use in the cell wall (in plants) or extracellular matrix (in animals).

- The sorting of lysosomal enzymes into specific vesicles for intracellular digestion.

- The modification of lipids to produce glycolipids, which are essential components of the cell membrane.

Physiological Mechanisms and the Pathological Context of Malaria

On a physiological level, the Golgi apparatus is essential for the maturation of proteins. When proteins arrive from the rough endoplasmic reticulum, they are often in a precursor form. Within the Golgi lumen, enzymes facilitate the folding and chemical alteration of these proteins, ensuring they are biologically active. This process is critical for the secretion of hormones like insulin and the production of digestive enzymes in the pancreas.

Because the Golgi was famously identified in Plasmodium species, it is important to understand the medical context of malaria. Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. Once the Plasmodium parasite enters the human bloodstream, it travels to the liver to mature and eventually infects red blood cells. The parasite relies heavily on its own internal endomembrane system, including a specialized Golgi apparatus, to export proteins that remodel the host’s red blood cells, allowing the parasite to evade the immune system and cause severe illness.

Symptoms of malaria typically include high fever, shaking chills, and flu-like illness. In severe cases, the disease can lead to organ failure, anemia, and cerebral malaria, which is often fatal if not treated promptly with antimalarial medications. The study of the parasite’s Golgi and intracellular trafficking mechanisms remains a significant area of research for developing new drugs that can disrupt the parasite’s ability to survive within the human host.

In conclusion, the Golgi apparatus is much more than a simple stack of membranes; it is a sophisticated processing plant that is fundamental to eukaryotic life. From its historical discovery in the context of parasitic disease to its everyday role in human physiology, it remains a cornerstone of cellular health. Understanding its structure and function not only aids in basic biological education but also provides critical insights into how diseases like malaria manipulate cellular pathways to thrive.