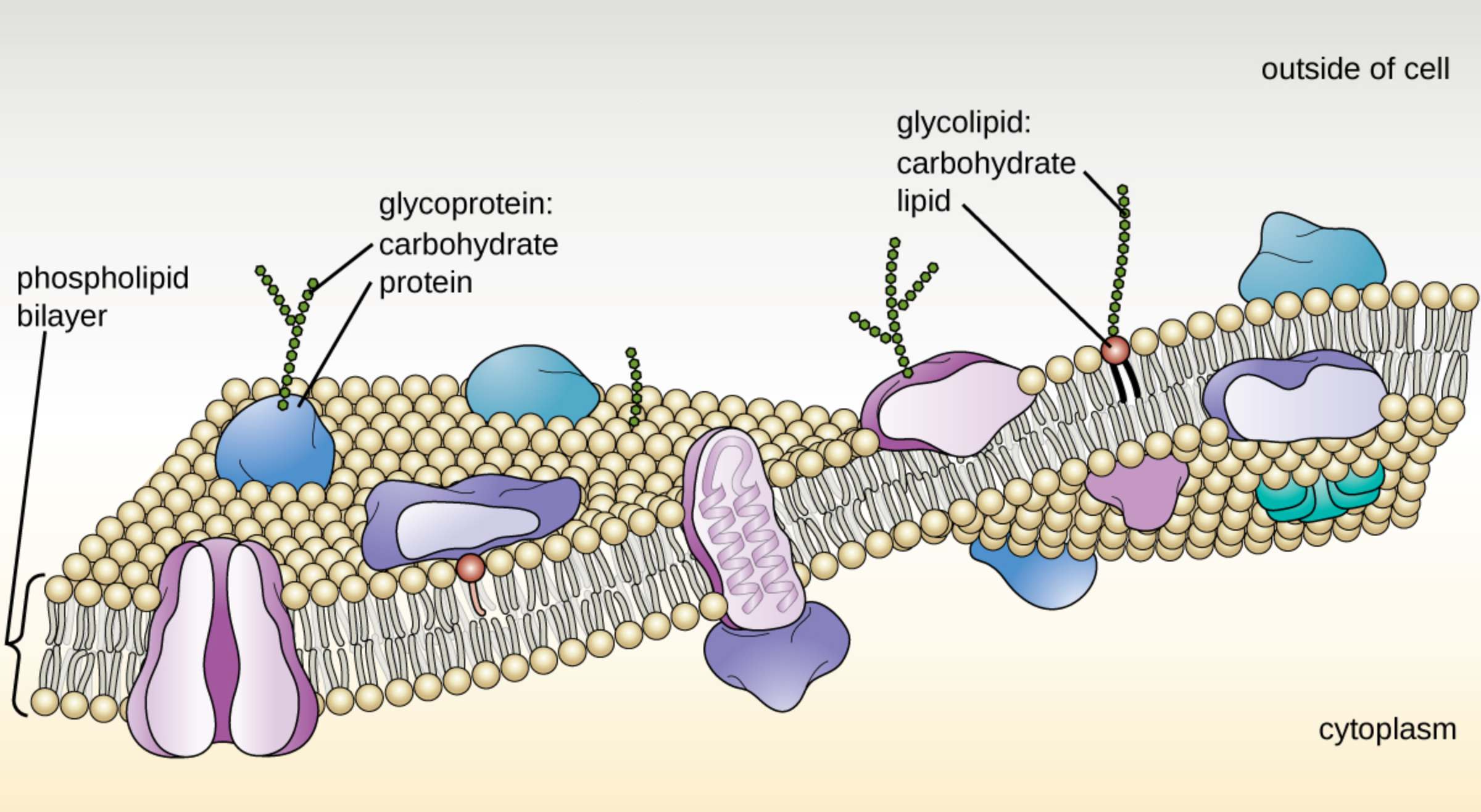

The bacterial plasma membrane is a dynamic and complex structure essential for maintaining cellular integrity and regulating biochemical exchanges between the cell and its environment. By utilizing the fluid mosaic model, we can visualize how a phospholipid bilayer integrates various proteins and carbohydrates to support life-sustaining functions such as nutrient uptake and waste removal. This biological barrier ensures that the internal environment remains stable despite the shifting conditions of the external world.

Phospholipid bilayer: This is the fundamental structural framework of the plasma membrane, consisting of two layers of phospholipids arranged tail-to-tail. The hydrophobic tails point inward away from water, while the hydrophilic heads face the aqueous environments of the cytoplasm and the extracellular space.

Glycoprotein: These molecules consist of a protein backbone with carbohydrate chains attached, extending outward into the extracellular environment. They play critical roles in cell-to-cell recognition, signaling, and acting as receptors for various molecular messengers.

Carbohydrate (as part of glycoprotein): These are short chains of sugar molecules that extend from the surface of the membrane-bound proteins. They form part of the glycocalyx, which protects the cell and assists in adhesion and communication.

Protein (as part of glycoprotein): These are integral or peripheral membrane proteins that serve as the anchor for carbohydrate chains. In addition to structural support, they often function as enzymes or transport channels for ions and molecules.

Glycolipid: A glycolipid is a lipid molecule covalently bonded to a carbohydrate chain, residing within the outer leaflet of the phospholipid bilayer. These structures contribute to membrane stability and facilitate cellular identification processes.

Carbohydrate (as part of glycolipid): Similar to those on glycoproteins, these sugar chains extend into the extracellular space to provide a unique “fingerprint” for the cell. This specificity is vital for the immune system to distinguish between self and non-self entities.

Lipid (as part of glycolipid): This refers to the fatty acid tails that anchor the carbohydrate moiety into the membrane’s core. This lipid component ensures that the carbohydrate remains securely attached to the surface of the cell.

Outside of cell: This region, also known as the extracellular space, contains the fluids and nutrients that surround the bacterium. It is the area from which the cell must selectively import resources while exporting metabolic waste.

Cytoplasm: This is the internal gelatinous substance of the cell where metabolic activities and genetic transcription occur. The plasma membrane serves as the primary barrier that maintains the specific internal conditions required for the cytoplasm to function optimally.

The Functional Dynamics of the Plasma Membrane

The plasma membrane is far more than a simple skin for the cell; it is a highly selective gatekeeper. The fluid mosaic model describes this membrane as a two-dimensional liquid in which lipid and protein molecules diffuse easily. This fluidity is essential for processes such as cell division, membrane fusion, and the proper functioning of transport proteins that must change shape to move cargo.

Within this bilayer, diverse proteins are embedded like tiles in a mosaic, each serving a specific physiological purpose. Some proteins act as channels allowing nutrients to enter, while others serve as pumps to remove toxins. The arrangement of these components is not static but changes in response to environmental temperature and nutritional availability.

Key features of the bacterial plasma membrane include:

- Selective permeability for the controlled transport of ions and small molecules.

- Site for metabolic processes like oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis.

- Anchoring point for the cytoskeleton and external structures like pili or flagella.

- Signal transduction pathways to sense and respond to external stimuli.

The presence of glycoproteins and glycolipids on the outer surface creates a complex “sugar coating” known as the glycocalyx. This layer is crucial for bacterial survival, as it helps the cell adhere to surfaces, protects it from dehydration, and can even help it evade the host’s immune system during an infection.

Biochemical Composition and Cellular Homeostasis

The primary role of the phospholipid bilayer is to create a hydrophobic barrier that prevents the free passage of water-soluble substances. This allows the cell to maintain homeostasis, ensuring that internal concentrations of ions like potassium and sodium are kept at levels distinct from the external environment. Without this strict regulation, the biochemical reactions necessary for life would cease to function efficiently.

Proteins embedded within the membrane are categorized as integral or peripheral. Integral proteins span the entire bilayer and often act as transporters or receptors. Peripheral proteins are loosely attached to the exterior or interior surfaces and often play roles in maintaining the cell’s shape or facilitating internal signaling pathways. Together, these components allow the bacterium to interact with the extracellular matrix and respond to its surroundings.

In conclusion, the fluid mosaic model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how bacteria survive and interact with their environment. By balancing structural stability with functional flexibility, the plasma membrane acts as the brain and heart of cellular boundary management. Recognizing the intricacies of these lipid and protein interactions is fundamental to microbiology and the development of new antibacterial treatments that target membrane integrity.