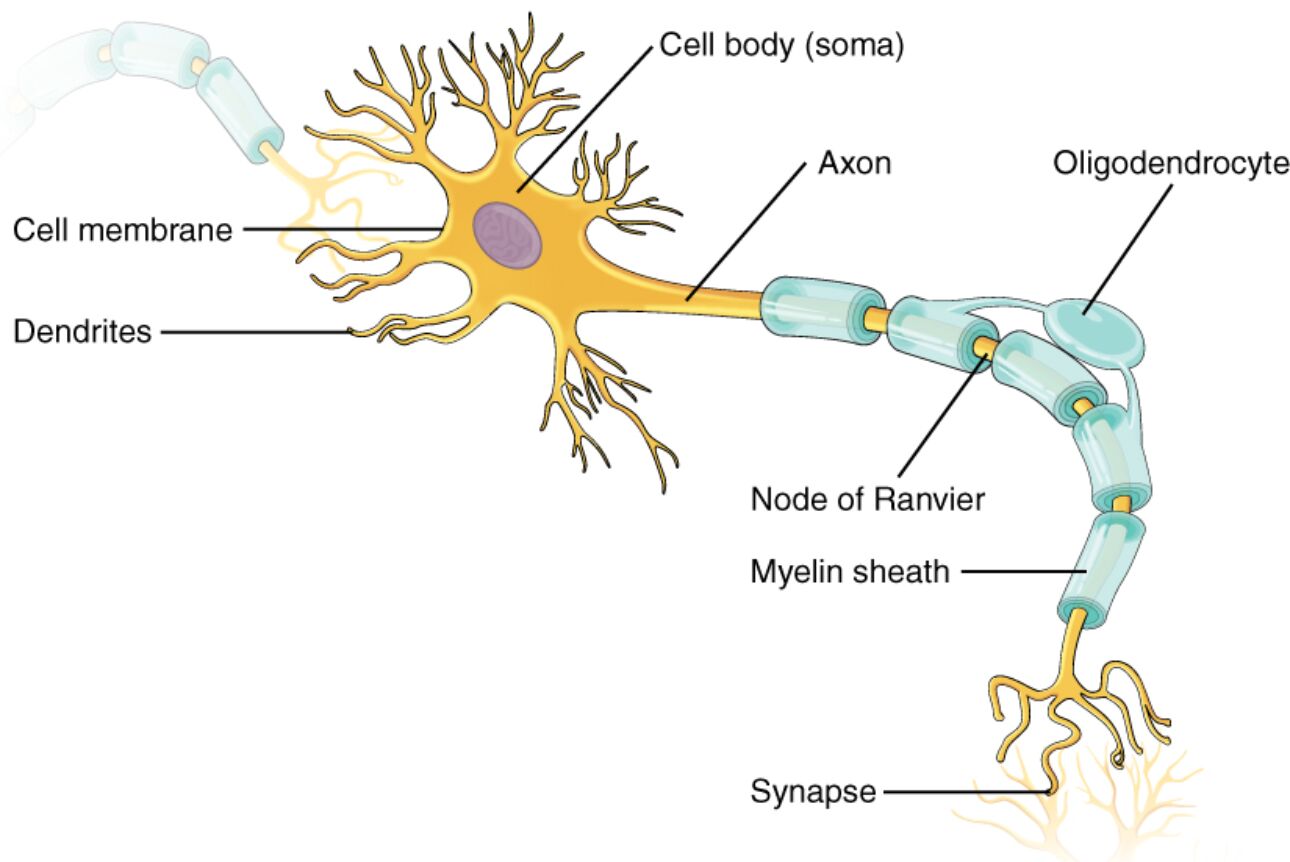

Neurons form the essential units of the nervous system, enabling the processing and transmission of electrical and chemical signals that coordinate bodily activities, from simple movements to complex behaviors. This illustrative diagram depicts a multipolar neuron typical in the central nervous system (CNS), showcasing its intricate structure that supports rapid communication across the body. By examining each labeled component, one can appreciate how these specialized cells maintain efficient neural networks, crucial for functions like sensation, memory, and reflex actions.

Labeled Parts of the Neuron

Cell body (soma )

The cell body, or soma, acts as the metabolic hub of the neuron, containing the nucleus and organelles that produce energy and synthesize proteins necessary for neuronal maintenance and repair. It integrates incoming signals from dendrites to determine whether to propagate an action potential along the axon.

Dendrites

Dendrites are highly branched extensions that extend from the cell body, primarily responsible for receiving synaptic inputs from adjacent neurons or sensory receptors. Their extensive surface area allows for the convergence of thousands of signals, which are then funneled to the soma for processing.

Cell membrane

The cell membrane surrounds the entire neuron, functioning as a lipid bilayer that controls the entry and exit of ions and molecules to preserve the cell’s internal environment. It plays a vital role in generating electrical gradients essential for nerve impulse conduction through embedded ion channels and receptors.

Axon

The axon is a slender, elongated process that conducts electrical impulses away from the soma toward other neurons or effector organs. In myelinated axons, it facilitates saltatory conduction, where signals leap between nodes to accelerate transmission speeds up to 120 meters per second.

Oligodendrocyte

Oligodendrocytes are glial cells in the CNS by producing myelin sheaths that wrap around axons to insulate them. Each oligodendrocyte can extend processes to myelinate multiple axons, enhancing signal propagation efficiency and protecting neuronal integrity.

Node of Ranvier

The node of Ranvier represents the unmyelinated gaps along the axon where ion channels cluster, allowing for the regeneration of sodium and potassium ions during action potential propagation. These nodes enable saltatory conduction, significantly increasing the energy efficiency and velocity of neural signaling.

Myelin sheath

The myelin sheath is a fatty insulating layer formed by oligodendrocytes around the axon, which prevents ion leakage and speeds up electrical impulse travel. Damage to the myelin sheath, as in multiple sclerosis, can impair nerve function, highlighting its importance in maintaining proper neurological performance.

Synapse

The synapse is the junction where the axon’s terminal communicates with another neuron’s dendrite or a target cell, transmitting signals via neurotransmitters such as glutamate or dopamine. This structure allows for precise modulation of information flow, with synaptic vesicles releasing chemicals that bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane.

In-Depth Exploration of Neuron Anatomy

The anatomy of a neuron is intricately tailored to its role in information processing, with each part contributing to the overall efficiency of neural circuits. This section breaks down the structural features, drawing from the labeled diagram to provide a deeper anatomical perspective.

- Neurons are classified into types such as multipolar, bipolar, and unipolar, with the illustrated multipolar variety predominant in the CNS for integrative functions.

- The overall length of a neuron can range from micrometers in local interneurons to over a meter in motor neurons extending from the spinal cord to limbs.

- Branching patterns in dendrites enhance receptive capabilities, often featuring spines that dynamically form and retract based on activity.

- Axonal varicosities in some neurons allow for en passant synapses, enabling multiple connections along the axon’s length rather than solely at terminals.

- Myelin thickness correlates with axon diameter, following a g-ratio optimized for conduction velocity in different neural pathways.

Physiological Functions of Neuronal Components

Physiological processes within neurons rely on electrochemical gradients and molecular interactions to transmit signals seamlessly. Understanding these functions illuminates how the labeled parts collaborate in everyday neural activity.

- The cell body houses ribosomes and rough ER for protein production, including ion pumps like Na+/K+-ATPase that restore resting membrane potential after firing.

- Dendrites not only receive but also locally compute signals through voltage-gated channels, contributing to phenomena like back-propagating action potentials.

- The cell membrane’s selective permeability, mediated by aquaporins and transporters, ensures osmotic balance and supports the resting potential of -70 mV.

- Axons can branch into terminals, each equipped with voltage-gated calcium channels that trigger vesicle release upon depolarization.

- Oligodendrocytes also provide metabolic support to axons via monocarboxylate transporters, supplying lactate as an alternative energy substrate during high activity.

- Nodes of Ranvier concentrate Nav1.6 sodium channels for rapid influx, with paranodal junctions sealing myelin to prevent current shunting.

- Myelin sheath reduces capacitance, allowing saltatory jumps that conserve ATP by limiting active pumping to nodes.

- Synapses can be electrical (via gap junctions for synchronized firing) or chemical, with the latter involving presynaptic active zones and postsynaptic densities for efficient transmission.

The Role of Neurons in the Nervous System

Neurons interconnect to form complex networks that underpin all aspects of cognition, sensation in the body. This interconnectedness underscores their significance beyond individual structures.

- Central nervous system neurons, like the multipolar one shown, process information in layers such as in the cerebral cortex, enabling higher-order thinking.

- Peripheral extensions link to muscles and glands, facilitating voluntary and reflex actions through efferent pathways.

- Glial interactions, exemplified by oligodendrocytes, outnumber neurons and modulate synaptic plasticity via cytokine signaling.

- Action potentials propagate as all-or-none events, with phases including rising, peak, falling, and after hyperpolarization, governed by Hodgkin-Huxley models.

- Neurotransmitter release at synapses follows calcium-dependent exocytosis, with reuptake mechanisms like EAAT transporters preventing prolonged excitation.

Advances in Neuron Research and Imaging

Recent advancements have enhanced our visualization and comprehension of neuronal structures. Techniques like confocal microscopy reveal subcellular details in labeled diagrams.

- Electron microscopy provides ultrastructural views of synapses, showing synaptic clefts of 20-40 nm and vesicle pools.

- Optogenetics allows for selective activation of axonal pathways, aiding studies on circuit functions in live models.

- Myelin imaging via diffusion tensor imaging (DTI tracks white matter tracts, correlating structure with behavioral outcomes.

- Research on nodes of Ranvier’s ion channel clustering involves ankyrin-G scaffolding proteins for precise localization.

- Synaptic studies employ patch-clamp techniques to measure currents, elucidating receptor kinetics in AMPA and GABA types.

Potential Pathologies Related to Neuronal Components

Although the diagram illustrates a typical healthy structure, disruptions can lead to disorders, offering insights into neuronal vulnerability.

- Soma damage from oxidative stress contributes to Alzheimer’s, with amyloid plaques impairing protein synthesis.

- Dendritic spine loss occurs in schizophrenia, reducing connectivity and altering signal integration.

- Axonal transport defects in ALS hinder microtubule-based delivery of mitochondria and neurotrophins.

- Demyelination by autoimmune attacks on oligodendrocytes characterizes multiple sclerosis, slowing conduction and causing symptoms like fatigue.

- Synaptic dysfunction in Parkinson’s involves dopamine depletion, affecting basal ganglia circuits for movement control.

In summary, the multipolar neuron depicted serves as a cornerstone of neural architecture, with its labeled parts harmoniously enabling the swift relay of information vital for survival and adaptation. Continued exploration of these components not only deepens biological knowledge but also paves the way for therapeutic interventions in neurological conditions, fostering advancements in neuroscience.