The symbiotic relationship between the bioluminescent bacterium Aliivibrio fischeri and the Hawaiian bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes) serves as a cornerstone model in microbiology and marine biology. This mutualistic interaction demonstrates how microscopic organisms can significantly influence the physiology and survival strategies of complex marine life through chemical signaling and light production.

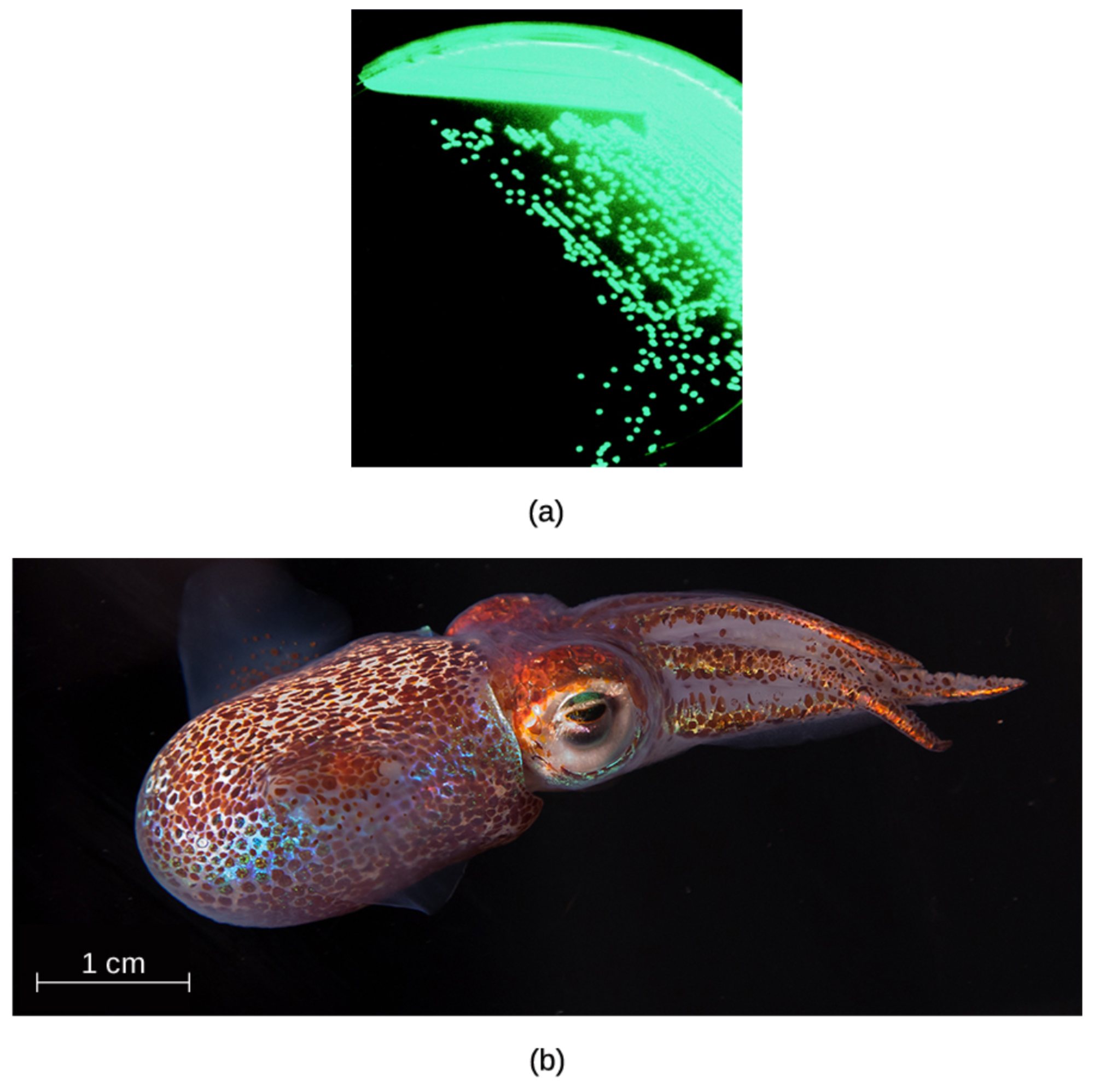

(a): This section of the image depicts a laboratory culture of Aliivibrio fischeri exhibiting intense bioluminescence on an agar plate. The visible glow is the result of a density-dependent chemical reaction that occurs only when the bacterial population is sufficiently high.

(b): This portion illustrates the Hawaiian bobtail squid, a cephalopod that has evolved a specialized light organ to house these glowing bacteria. By managing this internal bacterial colony, the squid can manipulate light to remain undetected by predators in the deep-sea water column.

Aliivibrio fischeri is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium found naturally in temperate and subtropical marine environments. While it can exist in a free-living state, it is most famous for its association with various marine animals, particularly the Hawaiian bobtail squid. This relationship is a classic example of mutualism, where both species benefit from the presence of the other: the squid gains a sophisticated camouflage mechanism, while the bacteria receive a nutrient-rich environment and protection from external stressors.

The colonization process is a marvel of biological specificity. Shortly after hatching, the juvenile squid must “recruit” the correct bacterial species from the surrounding seawater. The squid’s light organ is equipped with specialized ciliated surfaces and mucus secretions that specifically filter out other microbes, allowing only A. fischeri to enter and colonize the internal crypts. This ensures a pure culture of bioluminescent symbionts is maintained throughout the animal’s life.

To maintain the health of this symbiotic culture, the Hawaiian bobtail squid undergoes a daily cycle of venting. Every morning, the squid expels approximately 95% of its bacterial population into the surrounding environment. Throughout the day, the remaining bacteria multiply, reaching peak density and light-producing capacity just in time for the squid’s nocturnal activities.

Key aspects of this biological partnership include:

- Bacterial recruitment through chemotaxis and morphological changes in the host.

- Nutrient exchange, where the squid provides amino acids and proteins to the bacteria.

- The use of host-derived reflectors and lenses to direct the produced light.

- The regulation of light intensity to match the moon and stars above.

The Mechanics of Bioluminescence and Quorum Sensing

The light produced by Aliivibrio fischeri is not accidental; it is a highly regulated biochemical process. The core of this mechanism is the enzyme luciferase, which catalyzes the oxidation of a pigment called luciferin. This reaction requires molecular oxygen and reduced flavin mononucleotide (

FMNH2FMNH2), resulting in the emission of blue-green light. This bioluminescence is controlled by a genetic system known as the lux operon.

Central to the control of the lux operon is a phenomenon called quorum sensing. This is a form of bacterial communication that allows the colony to “sense” its own density. The bacteria release a signaling molecule called an autoinducer (specifically N-acyl homoserine lactone). When the concentration of this molecule reaches a certain threshold, which only happens in high-density environments like the squid’s light organ, the bacteria collectively activate the genes required for light production. In the open ocean, where bacterial concentrations are low, the autoinducer diffuses away, and the bacteria remain dark to conserve energy.

Physiological Strategy: Counter-Illumination

The primary anatomical purpose of the light organ in Euprymna scolopes is to facilitate a survival strategy known as counter-illumination. When the squid swims at night, its silhouette would normally be visible to predators lurking below, cast against the faint light of the moon and stars hitting the water’s surface. To avoid detection, the squid uses the light produced by A. fischeri to mimic the downward-shining light of the night sky.

The squid possesses physiological “shutters”—modified ink sac tissues—that it can open or close to adjust the amount of light emitted. Furthermore, the light organ contains specialized proteins that act as lenses to diffuse the light evenly across the squid’s ventral surface. By matching the intensity of the light coming from above, the squid effectively erases its shadow, becoming virtually invisible to predators watching from the depths. This intricate synchronization between animal behavior and bacterial physiology highlights the profound depth of co-evolution.

The study of Aliivibrio fischeri has provided invaluable insights into how bacteria talk to one another and how animals distinguish “friend” from “foe” at the microbial level. Understanding these pathways not only enriches our knowledge of marine ecosystems but also offers parallels to the human microbiome, where our own health depends on complex interactions with trillions of resident microbes.