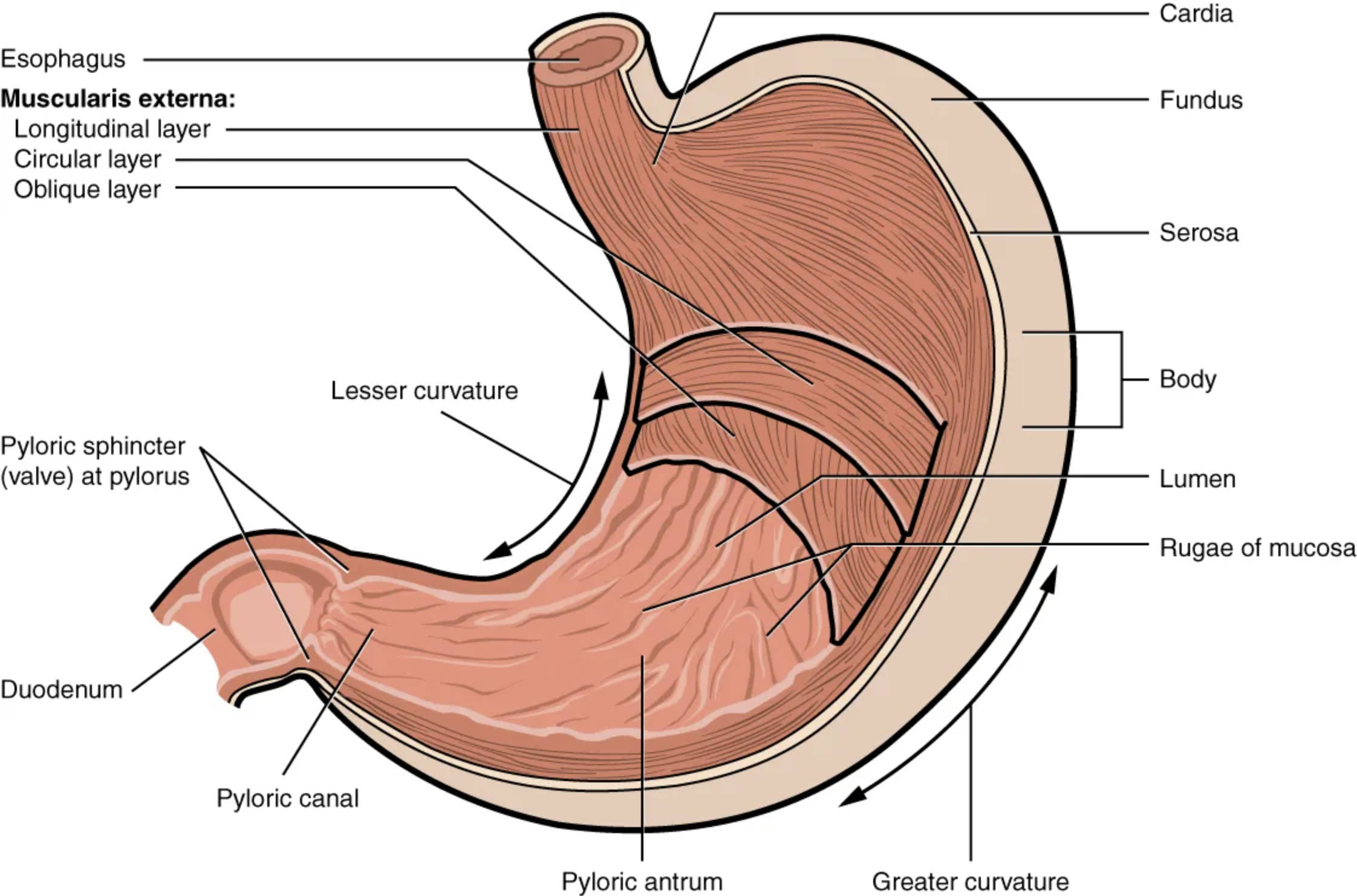

Explore the intricate stomach anatomical structure with this detailed diagram, highlighting its four major regions: cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. Learn how the unique oblique smooth muscle layer enables vigorous churning and mixing of food, a critical step in the digestive process.

The stomach is a remarkable, J-shaped organ situated in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen, playing a pivotal role in the human digestive system. Far from being a simple storage sac, it acts as a sophisticated bioreactor, initiating both mechanical and chemical digestion through its specialized structure and muscularity. This comprehensive overview delves into the distinct regions and unique muscle layers of the stomach, elucidating how these features facilitate the breakdown of food into a semi-liquid substance called chyme, ready for further processing in the small intestine.

Esophagus: The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. It transports food and liquids via peristaltic contractions, ensuring they reach the stomach for digestion.

Muscularis externa (Longitudinal layer): This is the outermost layer of smooth muscle in the stomach’s muscularis externa. Its longitudinal fibers primarily facilitate the shortening of the stomach, aiding in peristaltic movements.

Muscularis externa (Circular layer): Situated beneath the longitudinal layer, the circular smooth muscle layer of the stomach is responsible for constricting the lumen. This action is crucial for mixing food and propelling it through the digestive tract.

Muscularis externa (Oblique layer): Unique to the stomach, this innermost layer of smooth muscle provides an additional plane of contraction. The oblique fibers enable the stomach to perform vigorous churning and mixing movements, thoroughly blending food with gastric juices.

Pyloric sphincter (valve) at pylorus: This strong ring of smooth muscle, located at the junction of the pylorus and the duodenum, acts as a valve. It controls the rate at which chyme is released from the stomach into the small intestine, preventing rapid emptying.

Duodenum: The duodenum is the first and shortest segment of the small intestine, immediately following the stomach. It is here that chyme mixes with bile and pancreatic enzymes for further digestion.

Pyloric canal: The pyloric canal is the narrowest part of the pylorus, leading directly to the pyloric sphincter. It funnels the chyme towards the exit of the stomach.

Pyloric antrum: The pyloric antrum is the wider, more muscular region of the pylorus, located proximal to the pyloric canal. It serves as a mixing chamber and plays a key role in regulating gastric emptying.

Cardia: The cardia is the smallest, uppermost region of the stomach, surrounding the gastroesophageal junction where the esophagus enters. It contains mucus-secreting glands that protect the esophagus from stomach acid.

Fundus: The fundus is the dome-shaped upper part of the stomach, located superior to the cardia. It often contains trapped gases and plays a role in gastric distension and storage.

Serosa: The serosa is the outermost protective layer of the stomach, a smooth membrane covering its external surface. It is part of the visceral peritoneum, reducing friction against other abdominal organs.

Body: The body is the largest region of the stomach, situated between the fundus and the pyloric antrum. It is the main site for gastric juice production and significant mechanical and chemical digestion.

Lumen: The lumen refers to the inner, hollow space or cavity within the stomach where food is contained and processed. Its surface is lined with rugae to increase surface area.

Rugae of mucosa: These are large folds present on the inner lining (mucosa) of the stomach when it is empty. They allow the stomach to expand significantly to accommodate large meals and increase the surface area for digestion.

Lesser curvature: The lesser curvature is the shorter, concave medial border of the stomach. It forms the inner curve of the J-shape.

Greater curvature: The greater curvature is the longer, convex lateral border of the stomach. It forms the outer curve of the J-shape, extending from the fundus to the pylorus.

The Stomach: A Dynamic Digestive Organ

The stomach is a remarkably adaptable and efficient organ, central to the initial phases of digestion in humans. Beyond its primary function as a food reservoir, it rigorously processes ingested material through both mechanical churning and enzymatic breakdown, preparing it for the absorptive processes in the small intestine. The unique architectural design of the stomach, characterized by its distinct regions and specialized musculature, facilitates this complex digestive work.

The four major regions of the stomach are:

- Cardia: The entry point from the esophagus, ensuring unidirectional flow.

- Fundus: The dome-shaped upper section, primarily for storage and gas accumulation.

- Body: The largest central part, where most gastric juice secretion and mixing occur.

- Pylorus: The funnel-shaped lower section, regulating passage into the small intestine.

A hallmark of the stomach’s structure is its distinctive muscularis externa, which unlike other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, possesses three layers of smooth muscle: an outer longitudinal layer, a middle circular layer, and an inner oblique layer. This unique oblique layer is particularly crucial, as it provides the stomach with enhanced contractility, allowing for vigorous churning and mixing of food with highly acidic gastric juices. This mechanical action, combined with the chemical digestion initiated by enzymes such as pepsin (for proteins) and continued action of lingual lipase (for fats), transforms ingested food into a semi-liquid mixture known as chyme. The powerful contractions also facilitate gastric emptying, pushing chyme towards the pylorus. The pyloric sphincter then precisely regulates the release of this chyme into the duodenum, ensuring that the small intestine receives manageable portions for optimal further digestion and absorption, preventing an overload of acidic contents.

Disruptions to the stomach’s function can lead to various gastrointestinal disorders. Conditions like gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can occur if the lower esophageal sphincter (not explicitly part of the stomach but functionally linked) malfunctions, allowing stomach acid to enter the esophagus. Peptic ulcers, often caused by Helicobacter pylori infection or NSAID use, involve erosions in the stomach lining, while gastroparesis can result from impaired stomach motility. Understanding the stomach’s anatomy and physiology is therefore vital for diagnosing and managing such conditions, emphasizing the importance of this dynamic organ in maintaining overall digestive health.

In conclusion, the stomach is a critical and dynamic organ, expertly designed for both the temporary storage and initial breakdown of food. Its unique multi-layered musculature facilitates vigorous churning, while its specialized regions ensure a coordinated digestive process. The precise regulation of gastric emptying into the small intestine is essential for efficient nutrient assimilation. Appreciating the intricate structure and function of the stomach is fundamental to comprehending the entire digestive cascade and addressing potential gastrointestinal health concerns.