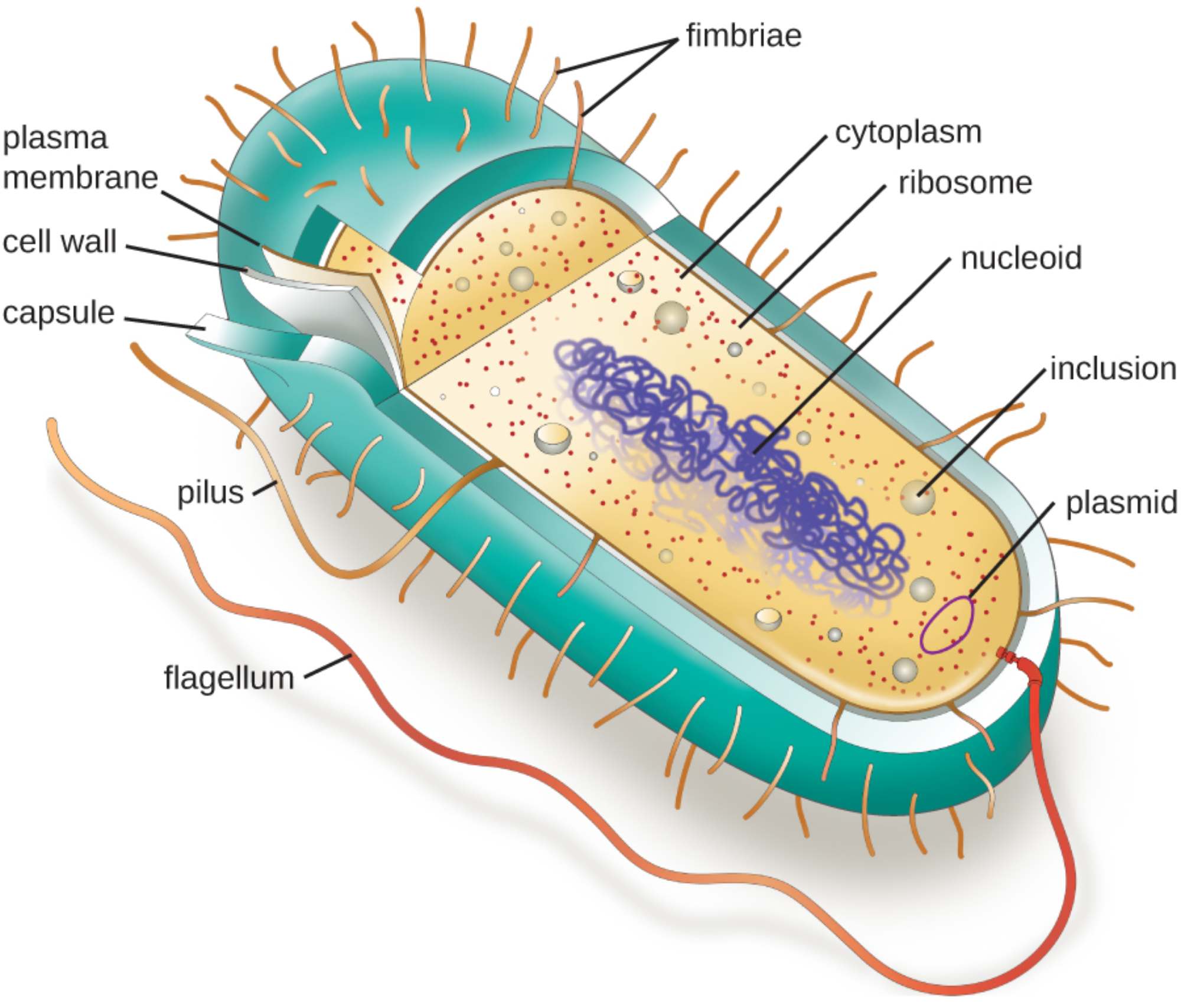

The typical prokaryotic cell represents the fundamental structural unit of organisms such as bacteria and archaea, characterized primarily by the absence of a membrane-bound nucleus. Understanding the complex anatomy of these microscopic entities is essential for microbiology and clinical medicine, as it reveals how they survive in diverse environments, replicate through binary fission, and interact with human hosts.

Fimbriae: These are short, hair-like appendages found on the surface of many bacterial cells. They play a critical role in attachment to surfaces or other cells, which is a vital step in the colonization process during an infection.

Cytoplasm: This is the gel-like substance that fills the interior of the cell, composed mostly of water, salts, and proteins. It serves as the primary site for metabolic reactions and houses all internal cellular components.

Ribosome: These small structures are the sites of protein synthesis, where genetic information is translated into functional proteins. Prokaryotic ribosomes are classified as 70S, which is structurally distinct from the 80S ribosomes found in eukaryotic cells.

Nucleoid: This is an irregularly shaped, non-membrane-bound region that contains the cell’s primary genetic material. The DNA within the nucleoid is typically a single, circular chromosome that carries the essential instructions for the cell’s survival and reproduction.

Inclusion: These are cytoplasmic aggregates that serve as storage vessels for nutrients or metabolic byproducts. Depending on the species, inclusions may store lipids, starch, or inorganic chemicals to be used when environmental resources are scarce.

Plasmid: These are small, circular pieces of extrachromosomal DNA that can replicate independently of the main chromosome. Plasmids often carry specialized genes, such as those responsible for antibiotic resistance, which can be shared between bacteria.

Flagellum: This long, whip-like appendage acts as a primary organelle for locomotion. By rotating like a motor, the flagellum allows the prokaryote to move toward nutrients or away from toxic substances in its environment.

Pilus: Similar to fimbriae but typically longer and fewer in number, pili are involved in various functions including attachment and motility. Specialized “sex pili” facilitate the transfer of DNA between bacterial cells through a process known as conjugation.

Capsule: This is a thick, polysaccharides-based outer layer that surrounds the cell wall of some bacteria. It provides significant protection against desiccation and helps the organism evade the host’s immune system by preventing phagocytosis.

Cell Wall: Located just outside the plasma membrane, the cell wall provides structural integrity and maintains the cell’s shape. In most bacteria, this layer is composed of peptidoglycan, a complex polymer that protects the cell from bursting due to osmotic pressure.

Plasma Membrane: This is a selectively permeable phospholipid bilayer that acts as a gatekeeper for the cell. It regulates the transport of molecules in and out of the cytoplasm and is the site for critical processes like ATP production and environmental sensing.

The Biological Significance of Prokaryotic Structures

Prokaryotes are among the most successful and diverse organisms on Earth, having adapted to almost every conceivable environment. Unlike eukaryotes, which rely on specialized membrane-bound organelles like mitochondria or chloroplasts, prokaryotes perform all life-sustaining functions within a single, streamlined compartment. This simplicity allows for rapid growth and metabolic flexibility, enabling bacteria to thrive in conditions ranging from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to the human gut.

From a clinical perspective, the unique anatomical features of prokaryotes are of paramount importance. Many modern medical treatments, such as antibiotics, are designed to specifically target bacterial structures that are absent in human cells. For example, penicillin works by inhibiting the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall, leading to cell death without harming the host’s own cells.

The structural components of a prokaryote are generally categorized into several functional groups:

- External Appendages: Includes structures like flagella, pili, and fimbriae used for movement and attachment.

- Cell Envelope: Comprises the capsule, cell wall, and plasma membrane, providing protection and regulation.

- Internal Components: Includes the cytoplasm, nucleoid, ribosomes, and plasmids responsible for metabolism and genetics.

The study of these structures also sheds light on bacterial pathogenesis, or the mechanism by which bacteria cause disease. Features like the capsule or fimbriae are often referred to as virulence factors because they directly enhance a bacterium’s ability to invade a host and cause harm. By understanding how these parts function, researchers can develop new vaccines and therapies to prevent bacterial colonization and spread.

Physiological Resilience and Adaptation

The physiological efficiency of the prokaryotic cell is driven by its high surface-area-to-volume ratio. Because they are so small, nutrients can diffuse quickly to any part of the cell, allowing for an incredibly fast metabolic rate. This efficiency is complemented by the presence of plasmids, which allow for rapid evolutionary adaptation. Through horizontal gene transfer, bacteria can quickly acquire new traits, such as the ability to degrade toxins or resist multiple classes of antibiotics, presenting a significant challenge in modern healthcare settings.

Furthermore, the cell wall’s composition determines how bacteria react to various environmental stresses and laboratory stains. The distinction between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, based on the thickness and composition of the peptidoglycan layer, is a fundamental diagnostic tool used in hospitals worldwide to guide initial treatment decisions for infections.

The intricate design of the prokaryotic cell is a testament to billions of years of evolutionary refinement. While they may lack the complex internal architecture of human cells, their anatomical specialized structures allow them to be highly resilient, versatile, and efficient. Continuing to explore the microscopic world of prokaryotic anatomy remains a cornerstone of biological research and is essential for the ongoing fight against infectious diseases.