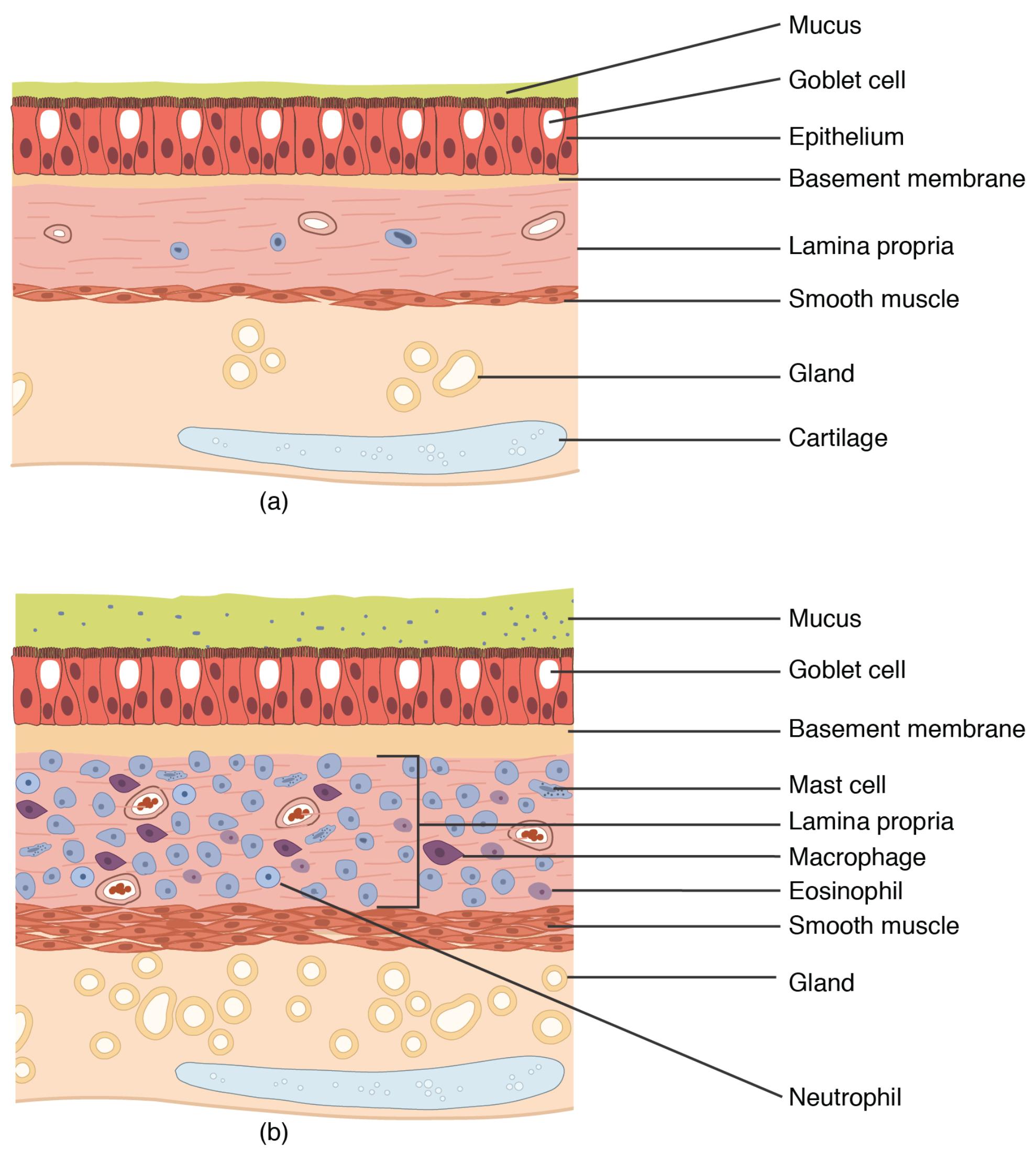

The comparison between normal lung tissue and bronchial asthma-affected tissue provides critical insights into respiratory health and disease pathology. This article examines the anatomical differences illustrated in the provided diagrams, highlighting the structural changes during an asthma attack and their implications for lung function.

Mucus: In normal lung tissue, this slippery substance traps dust and pathogens, aiding in their removal via the mucociliary escalator. During an asthma attack, its production increases significantly, contributing to airway obstruction.

Goblet cell: These cells secrete mucus in healthy lungs to maintain a protective layer, functioning efficiently under normal conditions. In asthma, their number and activity rise, leading to excessive mucus that clogs the airways.

Epithelium: This layer of cells lines the airways in normal tissue, providing a barrier against irritants and supporting gas exchange. In asthma, it becomes damaged and thickened, impairing normal respiratory function.

Basement membrane: In healthy lungs, this thin layer anchors the epithelium, offering structural support to the airway lining. In asthma, it thickens due to inflammation, contributing to airway remodeling.

Lamina propria: This connective tissue layer supports the epithelium in normal conditions, containing blood vessels and nerves. In asthma, it shows increased cellular infiltration, adding to tissue stiffness.

Smooth muscle: This layer regulates airway diameter in healthy lungs, allowing for smooth breathing adjustments. During an asthma attack, it hypertrophies, causing airway constriction.

Gland: These structures produce mucus and other secretions in normal tissue, maintaining airway hydration. In asthma, glandular hyperactivity exacerbates mucus buildup.

Cartilage: In normal lungs, this rigid structure provides structural support to keep airways open. It remains unchanged in asthma but is less effective due to surrounding inflammation.

Mast cell: Present in normal tissue, these cells release histamine in response to allergens, playing a minor role. In asthma, their activation intensifies, triggering inflammation and bronchoconstriction.

Macrophage: These immune cells clear debris in healthy lungs, maintaining a clean environment. In asthma, their presence increases, contributing to chronic inflammation.

Eosinophil: Rarely seen in normal tissue, these white blood cells are minimally active. In asthma, they infiltrate in large numbers, driving allergic inflammation.

Neutrophil: These cells are scarce in healthy lungs, responding only to acute infections. In asthma, their presence may increase during severe attacks, adding to tissue damage.

Anatomical Differences in Normal vs. Asthma-Affected Lung Tissue

The diagrams provide a clear contrast between healthy and asthmatic lung tissue, offering a visual guide to structural changes. This section explores the key anatomical features in both conditions.

- The mucus layer in normal tissue is thin and functional, while in asthma, it thickens, obstructing airflow.

- Goblet cells are sparse in healthy lungs but proliferate in asthma, producing excess mucus.

- The epithelium remains intact in normal conditions but shows damage and thickening during an asthma attack.

- The basement membrane is thin and supportive in healthy lungs, contrasting with its thickened state in asthma.

Cellular and Immune Responses in Asthma

The immune response plays a significant role in asthma, with specific cells driving the inflammatory process. This part delves into the cellular changes observed in the diagrams.

- Mast cells remain dormant in normal tissue but become highly active in asthma, releasing mediators like histamine.

- Eosinophils are rare in healthy lungs but dominate in asthma, contributing to allergic reactions.

- Macrophages increase in number during asthma, promoting chronic inflammation.

- Neutrophils may appear in severe asthma cases, adding to the inflammatory burden.

Impact of Structural Changes on Respiratory Function

Structural alterations in asthma significantly affect breathing, with each layer contributing to the disease’s severity. This section outlines the physiological impact.

- The thickened smooth muscle in asthma causes airway narrowing, making breathing difficult.

- Excessive mucus and gland activity in asthma lead to blockages, reducing airflow.

- The lamina propria’s inflammation in asthma stiffens the airways, impairing elasticity.

- Cartilage, though unchanged, becomes less effective due to surrounding tissue swelling.

Understanding Bronchial Asthma and Management

Bronchial asthma is a chronic condition characterized by airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness, often triggered by allergens or irritants. This section provides an overview of the disease and its management strategies.

- Asthma leads to reversible airway obstruction, with symptoms like wheezing and shortness of breath.

- Inhaled corticosteroids reduce inflammation, targeting eosinophils and mast cells.

- Bronchodilators relax smooth muscle, alleviating acute airway constriction.

- Avoiding triggers, such as pollen or smoke, helps manage symptoms effectively.

Conclusion

Comparing normal lung tissue with bronchial asthma-affected tissue reveals the profound impact of this condition on respiratory anatomy and function. The increased presence of eosinophils, thickened mucus, and hypertrophied smooth muscle in asthma underscores the need for targeted treatments to restore normal breathing. This detailed analysis enhances understanding of asthma’s mechanisms, paving the way for better management and improved quality of life.