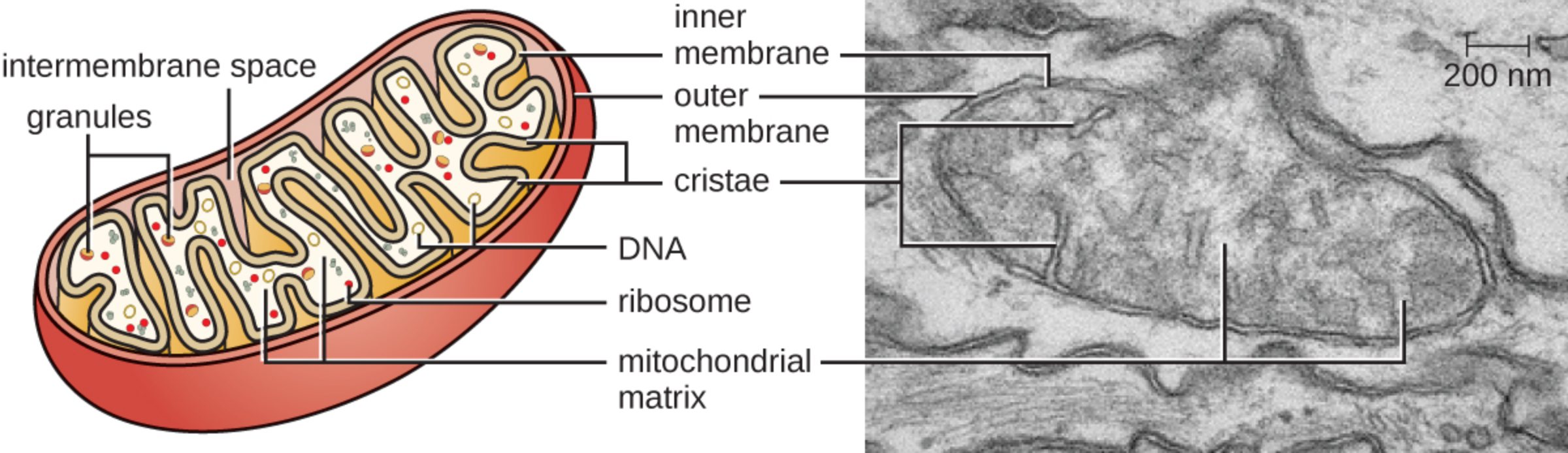

The mitochondrion is a sophisticated double-membrane organelle primarily responsible for generating the chemical energy required to power cellular biochemical reactions. Understanding its intricate structural components, such as the cristae and the mitochondrial matrix, is fundamental to grasping how human metabolism functions at a microscopic level.

Intermembrane space: This is the narrow region situated between the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes. It plays a critical role in oxidative phosphorylation by serving as a reservoir for protons, creating an electrochemical gradient necessary for energy synthesis.

Granules: These small, dense structures located within the matrix are primarily composed of phospholipids and ions like calcium. They function as storage sites that help maintain the internal ionic balance of the organelle, ensuring optimal enzymatic activity.

Inner membrane: This highly specialized lipid bilayer is characterized by its impermeability to most ions and small molecules. It houses the components of the electron transport chain and ATP synthase, making it the primary site of energy conversion within the cell.

Outer membrane: The outer membrane acts as a protective boundary that separates the mitochondrion from the surrounding cytoplasm. It contains specialized proteins called porins that allow the passage of small molecules and ions, facilitating communication between the organelle and the rest of the cell.

Cristae: These are the numerous inward folds of the inner membrane that significantly increase the available surface area. By expanding the surface area, cristae allow for a much higher density of chemical reactions, thereby maximizing the efficiency of energy production.

DNA: Mitochondria possess their own unique genetic material, distinct from the DNA found in the cell nucleus. This circular mitochondrial DNA encodes essential proteins required for the organelle’s function and is inherited almost exclusively through the maternal lineage.

Ribosome: These small molecular machines are responsible for synthesizing proteins directly within the mitochondrial matrix. Because mitochondria have their own ribosomes, they can produce some of their own structural and functional proteins independently of the cell’s main protein-making machinery.

Mitochondrial matrix: The matrix is the innermost compartment filled with a dense fluid containing a cocktail of enzymes, ribosomes, and DNA. It serves as the primary site for the citric acid cycle, also known as the Krebs cycle, where organic molecules are broken down to release stored energy.

The Biological Significance of Mitochondria

Mitochondria are often referred to as the “powerhouses” of the cell, but their role extends far beyond simple energy generation. These organelles are dynamic structures that undergo constant fission and fusion to adapt to the metabolic demands of the tissue they inhabit. High-energy tissues, such as the heart and skeletal muscles, contain thousands of mitochondria per cell to ensure a steady supply of energy.

Beyond energy production, mitochondria are central to regulating cellular life and death. They play a pivotal role in signaling, cellular differentiation, and the control of the cell cycle. Furthermore, they are responsible for the regulation of calcium homeostasis, which is essential for muscle contraction and neurotransmitter release.

Key functions of the mitochondria include:

- Synthesis of chemical energy through aerobic pathways.

- Regulation of programmed cell death (apoptosis).

- Heat production through non-shivering thermogenesis.

- The breakdown of fatty acids via beta-oxidation.

The structural integrity of the mitochondrion is paramount to its function. Any disruption to the membranes or the depletion of mitochondrial DNA can lead to significant metabolic dysfunction. Because these organelles are the primary source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), they are also susceptible to oxidative damage, which is a major factor in aging and various degenerative conditions.

Physiological Mechanisms of Energy Synthesis

The process of cellular respiration is the cornerstone of mitochondrial physiology. It begins in the cytoplasm but reaches its high-efficiency peak within the mitochondrial matrix and inner membrane. During this process, glucose-derived molecules undergo a series of transformations, ultimately feeding electrons into the electron transport chain.

The efficiency of this system relies on the electrochemical proton gradient established across the inner membrane. As electrons move through protein complexes, protons are pumped into the intermembrane space. The resulting “proton-motive force” drives the rotation of the ATP synthase enzyme, leading to the creation of ATP (adenosine triphosphate). This mechanism, known as oxidative phosphorylation, is the most efficient way for aerobic organisms to harvest energy from nutrients.

Genetic health within the mitochondrion is another critical area of medical study. Unlike nuclear DNA, mitochondrial DNA lacks the protective histone proteins and robust repair mechanisms found in the nucleus. This makes it more prone to mutations. When these mutations reach a certain threshold, they can manifest as mitochondrial diseases, often affecting organ systems with the highest energy demands, such as the brain, heart, and liver.

In summary, the mitochondrion is a marvel of biological engineering, featuring a complex architecture that facilitates the life-sustaining processes of energy metabolism. From the protective outer membrane to the energy-harvesting cristae, every component works in harmony to maintain the vitality of the human body. Understanding these microscopic structures is essential for advancing our knowledge of metabolic health, longevity, and the treatment of complex genetic disorders.