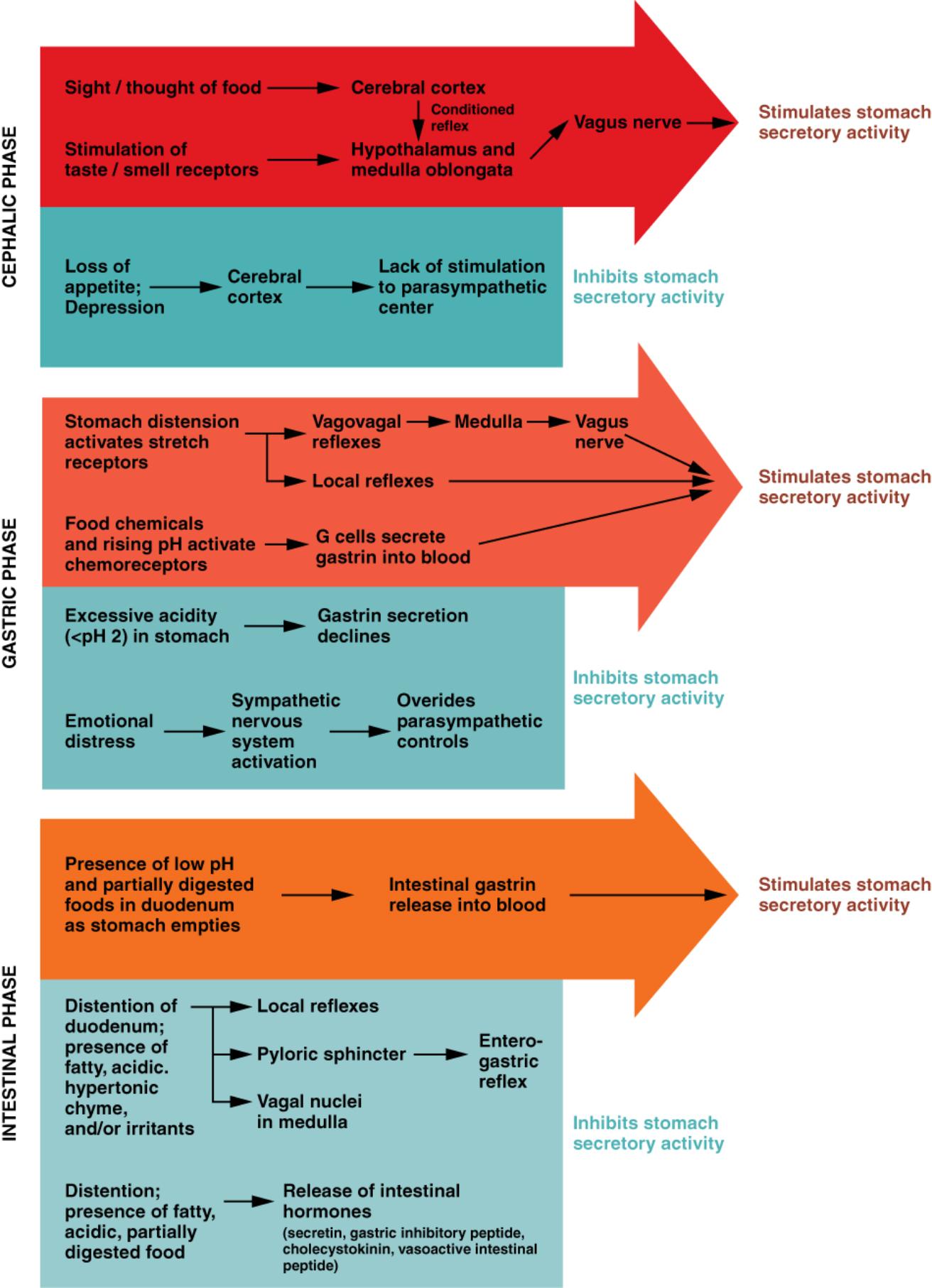

Explore the fascinating process of gastric secretion, a meticulously coordinated physiological event crucial for digestion. This article breaks down the three distinct phases—cephalic, gastric, and intestinal—detailing how both stimulatory and inhibitory mechanisms regulate the production of gastric juice to optimize nutrient breakdown.

CEPHALIC PHASE: This initial phase of gastric secretion occurs even before food enters the stomach. It is primarily driven by sensory input like the sight, smell, taste, or even the thought of food, preparing the stomach for its upcoming digestive tasks.

Sight / thought of food: The anticipation of eating, triggered by seeing or thinking about food, initiates a neural response. This psychological stimulus sends signals to the brain, preparing the digestive system for incoming nutrients.

Cerebral cortex: This part of the brain is responsible for processing sensory information and conscious thought related to food. It integrates visual and olfactory cues, translating them into signals that impact gastric function.

Conditioned reflex: This refers to learned associations between specific stimuli (like a dinner bell) and the act of eating. Over time, these reflexes can independently trigger gastric secretions, demonstrating the brain’s anticipatory role.

Vagus nerve: A crucial cranial nerve, the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) acts as a primary conduit for parasympathetic signals from the brain to the stomach. Its activation during the cephalic phase directly stimulates gastric juice secretion.

Stimulates stomach secretory activity: This indicates that the neural pathways activated during the cephalic phase lead to an increase in the production and release of gastric juice. This preparatory step ensures the stomach is ready to efficiently process food.

Stimulation of taste / smell receptors: When food is tasted or smelled, sensory receptors send signals to the brain. These direct sensory inputs are powerful activators of the cephalic phase, bypassing the need for conscious thought.

Hypothalamus and medulla oblongata: These brain regions play a critical role in integrating and relaying signals related to hunger, satiety, and digestive reflexes. They act as control centers, coordinating the body’s response to food stimuli.

Loss of appetite; Depression: Emotional and psychological states, such as a loss of appetite or depression, can significantly impact gastric function. These conditions often lead to a reduction in the body’s readiness for digestion.

Inhibits stomach secretory activity: This outcome indicates that negative emotional or physiological states can suppress the production of gastric juice. The brain’s influence on digestion is profound, illustrating the mind-body connection.

Lack of stimulation to parasympathetic center: When appetite is lost or depression occurs, there is reduced activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, which typically promotes digestion. This reduction leads to decreased gastric secretion.

GASTRIC PHASE: This phase begins when food actually enters the stomach, building upon the preparatory work of the cephalic phase. It is characterized by local reflexes and hormonal responses triggered by the presence of food within the stomach itself.

Stomach distension activates stretch receptors: As food fills the stomach, the muscular walls stretch, activating specialized mechanoreceptors. These stretch receptors send signals that initiate digestive responses, coordinating the stomach’s activity.

Vagovagal reflexes: These are long reflexes involving both afferent and efferent pathways of the vagus nerve, traveling to and from the brainstem (medulla). They significantly amplify gastric secretion in response to stomach distension.

Medulla: The medulla oblongata in the brainstem serves as a vital relay center for digestive reflexes. It processes signals from the stomach and orchestrates appropriate responses via the vagus nerve.

Local reflexes: These are short reflexes that occur entirely within the stomach’s enteric nervous system, independent of the central nervous system. They contribute to localized increases in gastric secretion in response to food presence.

Food chemicals and rising pH activate chemoreceptors: The presence of proteins, amino acids, and other food components, along with a slight increase in stomach pH due to food buffering acid, stimulates specific chemoreceptors. These receptors play a key role in signaling the need for further digestion.

G cells secrete gastrin into blood: Activated by food chemicals and rising pH, specialized G cells in the stomach mucosa release the hormone gastrin. Gastrin travels through the bloodstream to stimulate parietal cells to secrete hydrochloric acid.

Excessive acidity (pH < 2) in stomach: When the stomach contents become too acidic, typically when the pH drops below 2, a feedback mechanism is triggered. This strong acidity signals that sufficient acid has been produced.

Gastrin secretion declines: High acidity directly inhibits the G cells from releasing more gastrin. This negative feedback loop is essential for preventing excessive acid production, which could damage the stomach lining.

Sympathetic nervous system activation: Stress or other physiological challenges can activate the sympathetic nervous system. This activation prepares the body for “fight or flight” responses, often at the expense of digestive processes.

Emotional distress: Intense emotions like stress, anxiety, or fear can significantly impact digestion. The body’s response to emotional distress prioritizes immediate survival, diverting resources away from the digestive system.

Overrides parasympathetic controls: During periods of stress or emotional distress, the sympathetic nervous system can suppress the pro-digestive actions of the parasympathetic nervous system. This results in an inhibition of gastric secretions and slowed digestion.

INTESTINAL PHASE: This final phase begins when partially digested food, now called chyme, starts to enter the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). This phase involves both stimulatory and inhibitory signals that regulate stomach emptying and further digestion.

Presence of low pH and partially digested food in duodenum as stomach empties: As acidic chyme moves from the stomach into the duodenum, the low pH and the presence of fats and proteins trigger specific responses. This influx signals the small intestine to prepare for digestion.

Intestinal gastrin release into blood: Initially, the presence of chyme in the duodenum can stimulate the release of intestinal gastrin. This hormone briefly encourages gastric activity, facilitating the complete emptying of the stomach.

Distention of duodenum; presence of fatty acid, hypertonic chyme, and/or irritants: As the duodenum stretches with incoming chyme and detects specific components like fats or hypertonic solutions, it triggers inhibitory reflexes. These signals prevent overloading the small intestine.

Local reflexes: Short reflexes within the enteric nervous system of the duodenum respond to distention and chemical composition. These reflexes locally inhibit gastric emptying and secretion, allowing the small intestine time to process the chyme.

Pyloric sphincter: This muscular valve controls the flow of chyme from the stomach into the duodenum. Its constriction, regulated by duodenal signals, ensures that only small, manageable amounts of chyme are released at a time.

Vagal nuclei in medulla: Signals from the duodenum can also travel via long reflexes to the vagal nuclei in the medulla. This central nervous system involvement allows for a more widespread and potent inhibition of gastric function.

Entero-gastric reflex: This is a powerful reflex initiated by stimuli in the duodenum that inhibits gastric secretion and motility. It plays a crucial role in regulating the rate at which chyme enters the small intestine, preventing duodenal overload.

Distention; presence of fatty, acidic, partially digested food: These specific stimuli within the duodenum act as strong triggers for the release of various intestinal hormones. These hormones are key players in coordinating digestive activities between the stomach and small intestine.

Release of intestinal hormones (secretin, gastric inhibitory peptide, cholecystokinin, vasoactive intestinal peptide): In response to duodenal stimuli, specialized enteroendocrine cells release a suite of hormones. Secretin primarily inhibits acid secretion, while cholecystokinin (CCK) slows gastric emptying and stimulates pancreatic enzyme release. Gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) also inhibits gastric secretion, and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) has various effects, including vasodilation and smooth muscle relaxation.

The regulation of gastric secretion is a complex and exquisitely coordinated process involving neural and hormonal mechanisms, unfolding in three distinct yet interconnected phases: the cephalic, gastric, and intestinal phases. This intricate system ensures that the stomach produces the appropriate amount of gastric juice precisely when needed, optimizing the initial stages of food breakdown. From the moment we anticipate a meal to the time food leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine, a continuous feedback loop of signals dictates the stomach’s activity.

The cephalic phase, often overlooked, highlights the powerful influence of the brain on digestion. Simply thinking about food can kickstart the production of gastric juice, preparing the stomach for its upcoming task. This anticipatory response is primarily mediated by the vagus nerve, a key component of the parasympathetic nervous system. However, emotional states like stress or depression can disrupt this initial preparation, illustrating the profound impact of psychological factors on physiological processes.

Once food enters the stomach, the gastric phase takes over, intensifying secretory activity through both local reflexes and hormonal cascades. Stomach distension and the chemical composition of food are critical triggers, leading to the release of gastrin, a hormone that further stimulates acid secretion. This phase demonstrates the stomach’s self-regulatory capacity, where the presence of food directly signals the need for more digestive enzymes and acid.

Finally, as the partially digested food (chyme) moves into the small intestine, the intestinal phase emerges. This phase primarily focuses on slowing down gastric activity to prevent the small intestine from being overwhelmed. Hormones like secretin and cholecystokinin play a crucial role here, inhibiting gastric secretions and motility, thereby ensuring efficient digestion and absorption in the small intestine. Understanding these phases is fundamental to appreciating the sophistication of the human digestive system.