The diversity of eukaryotic cells is often exemplified by the unique morphologies found in the world of microscopic microorganisms. Vorticella, characterized by its distinctive bell-shaped body and a highly contractile stalk, represents a fascinating model for studying cellular motility and specialized feeding mechanisms. This guide explores the anatomical and physiological traits that allow these single-celled organisms to thrive in aquatic ecosystems by leveraging their complex structural adaptations.

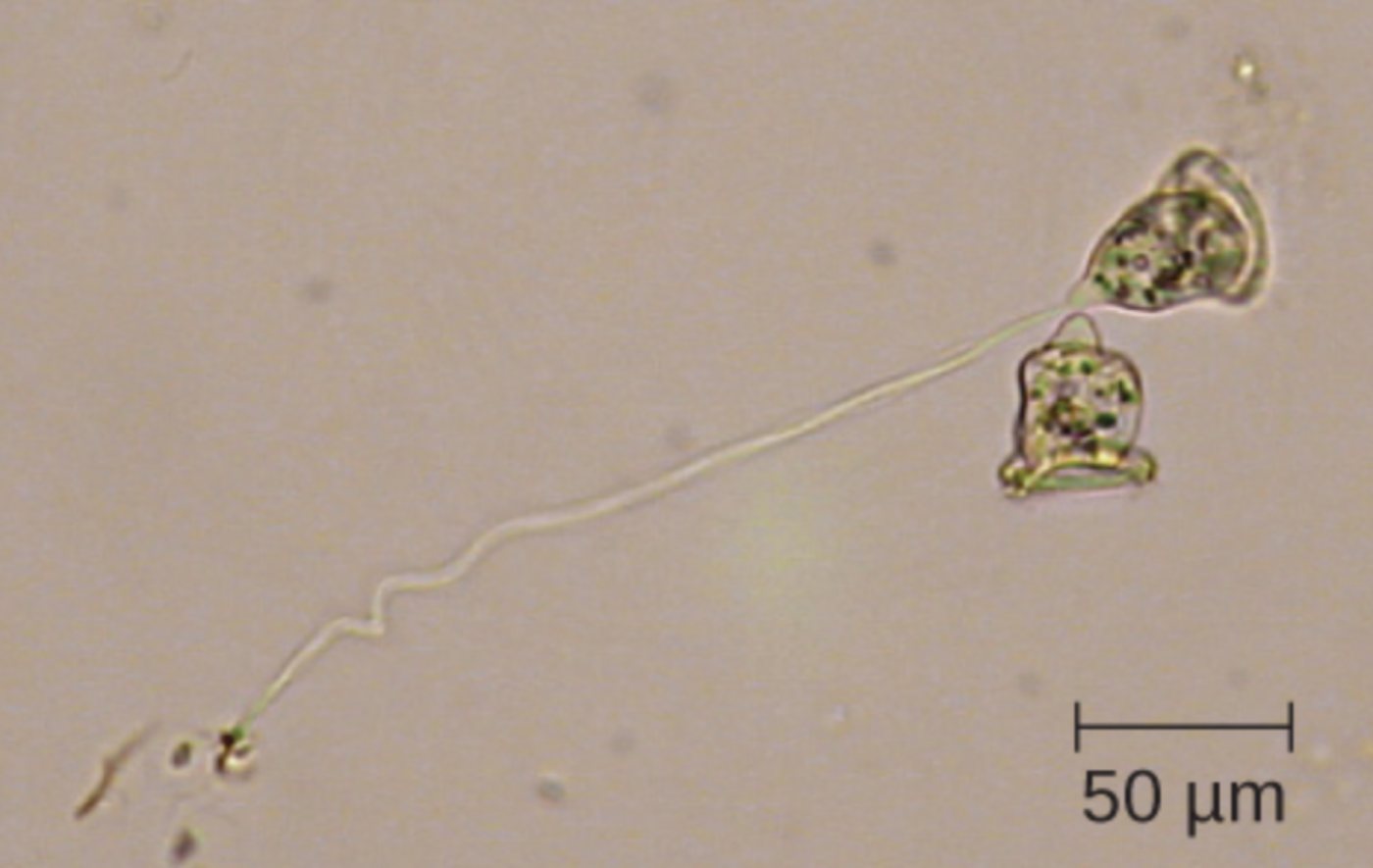

50 μm: This scale bar indicates a length of fifty micrometers, serving as a critical reference for determining the actual size of the organism under a microscope. By comparing the zooid and stalk to this measurement, researchers can appreciate the intricate structural complexity present at such a minute microscopic scale.

The evolution of eukaryotic life has led to an astonishing array of cellular architectures, each specifically tailored to perform distinct biological tasks. While many cells are specialized for movement or structural support within multicellular organisms, single-celled eukaryotes often integrate multiple complex systems into a single unit. The genus Vorticella provides a prime example of this morphological specialization, featuring a bell-shaped body and a mechanical stalk that is among the fastest moving structures in the biological world.

These organisms belong to the phylum Ciliophora and are commonly found in both freshwater and marine environments. Unlike many of their free-swimming relatives, these cells are primarily sessile, meaning they remain attached to a substrate for the majority of their life cycle. This lifestyle has driven the development of unique feeding and defensive mechanisms that are readily visible through high-resolution light microscopy.

Key anatomical and physiological hallmarks of Vorticella include:

- The zooid, or bell-shaped body, which houses the primary metabolic and reproductive organelles.

- A peripheral ring of cilia used to generate localized water currents for filter feeding.

- A highly specialized contractile stalk containing a proteinaceous structure known as a spasmoneme.

- A dual nuclear system composed of a large macronucleus and a smaller micronucleus.

As a complex eukaryotic protozoan, Vorticella demonstrates how intracellular components can perform mechanical work similar to the muscles in higher organisms. The most striking feature is the stalk, which can contract into a tight coil in mere milliseconds when the cell is disturbed. This rapid withdrawal is a protective reflex designed to pull the delicate zooid away from potential predators or harmful environmental shifts.

The Mechanics of the Contractile Stalk

The stalk of Vorticella is not merely a passive tether; it is a sophisticated engine powered by a structure called the spasmoneme. Unlike eukaryotic muscles that rely on ATP-driven myosin, the spasmoneme contracts through a calcium-dependent mechanism. When a stimulus triggers the release of calcium ions into the stalk, the spasmoneme proteins undergo a rapid conformational change, causing the stalk to coil like a spring.

This process is entirely independent of traditional energy molecules like ATP for the actual contraction phase, although ATP is required later to pump the calcium back into storage compartments to allow the stalk to re-extend. This physiological efficiency allows the cell to react to threats with speeds exceeding several centimeters per second, an incredible feat given the small dimensions involved.

Feeding and Ciliary Action

The “bell” of the organism is essentially a specialized feeding apparatus. At the top of the zooid sits the peristome, which is surrounded by rows of cilia that beat in a coordinated, rhythmic fashion. This ciliary action creates a vortex in the surrounding water, drawing in bacteria and small organic particles. Once the particles are trapped, they are directed into the cytostome (cell mouth) and eventually packaged into food vacuoles for intracellular digestion.

This filter-feeding strategy requires the cell to maintain a constant position in the water column, which is why the stalk is so vital. By remaining anchored, the Vorticella can continuously process large volumes of water without expending the energy required for swimming. This anatomical arrangement ensures a steady supply of nutrients, supporting the high metabolic demands of its contractile machinery.

Internal Organelle Function and Osmoregulation

Internally, the cell manages its genetic material through a dimorphic nuclear system. The macronucleus, which often appears C-shaped or like a thick ribbon, handles the day-to-day transcriptions required for metabolism and protein synthesis. Meanwhile, the smaller micronucleus is reserved for genetic exchange during conjugation, ensuring the long-term survival of the lineage through genetic recombination.

Because Vorticella often lives in freshwater environments where the external environment is hypotonic, it must constantly fight against the influx of water. This is achieved through osmoregulation facilitated by a prominent contractile vacuole. This organelle periodically collects excess water from the cytoplasm and forcefully expels it from the cell, maintaining the proper internal pressure and preventing the cell from bursting. This delicate balance of structural mechanics and internal homeostasis highlights the incredible complexity found within different shapes of eukaryotic cells.

In summary, the bell-shaped Vorticella serves as a testament to the versatility of eukaryotic design. From the high-speed coiling of its stalk to the efficient vortex created by its cilia, every anatomical detail is finely tuned to support a sessile, filter-feeding existence. By studying these specialized organisms, we gain deeper insights into the fundamental principles of cellular movement, genetic management, and environmental adaptation that characterize all life at the microscopic level.