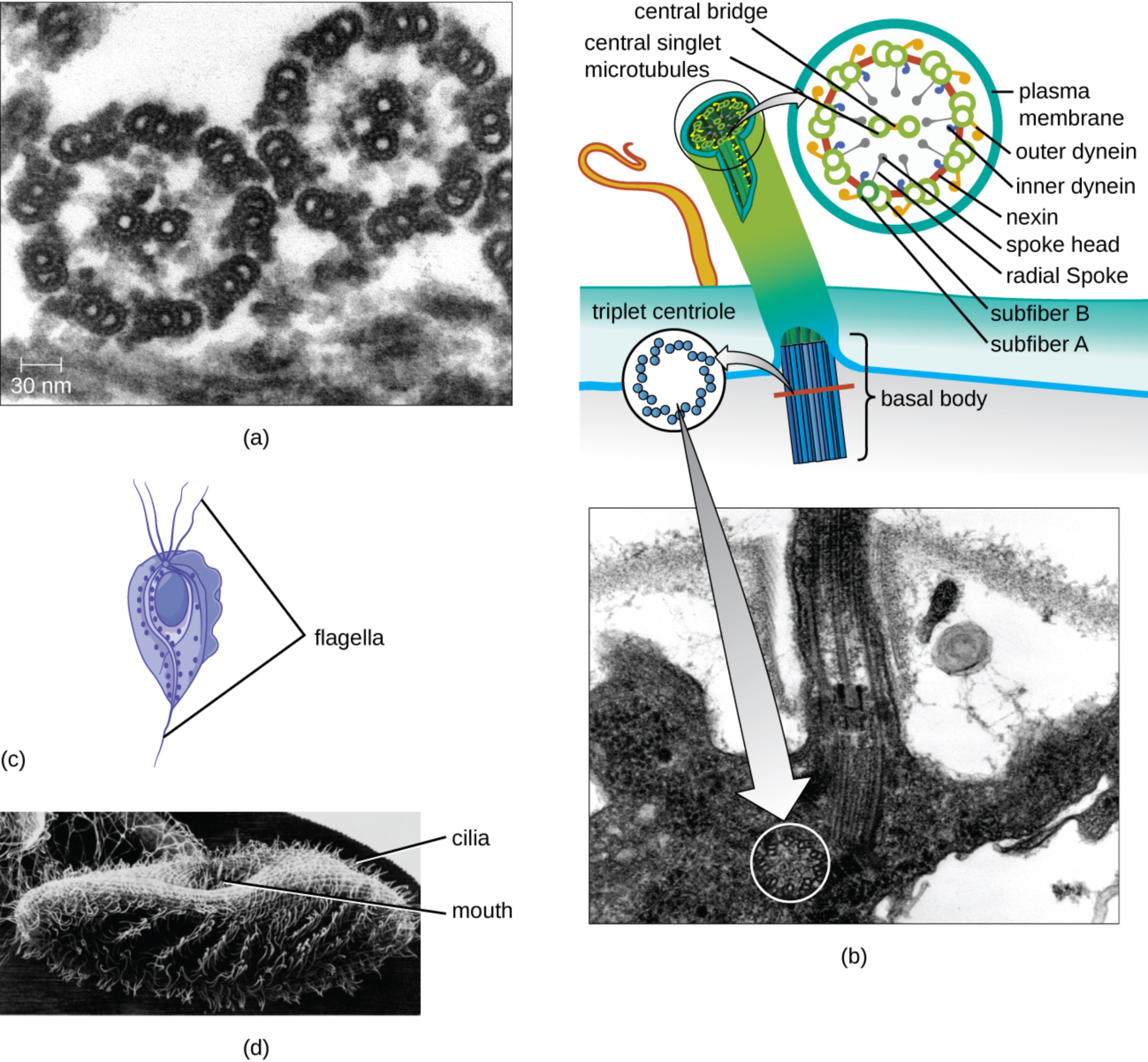

Eukaryotic cilia and flagella are specialized organelles that play essential roles in cellular motility, sensory perception, and the survival of various parasitic organisms. These structures are defined by a highly conserved “9+2” arrangement of microtubules, which provides the mechanical framework necessary for complex whip-like or rhythmic beating motions. In the human body, similar structures are vital for moving mucus out of the respiratory tract or propelling sperm, while in the world of microbiology, they enable parasites like Trichomonas vaginalis to infect human hosts.

central bridge: This is the structural connection that links the two central singlet microtubules within the core of the axoneme. It stabilizes the central pair, ensuring they remain properly spaced during the high-stress motions of cellular beating.

central singlet microtubules: These are the two individual microtubules located at the center of the 9+2 array in eukaryotic cilia and flagella. They serve as a structural reference point and are involved in regulating the signals that control microtubule sliding.

plasma membrane: This outer lipid bilayer encloses the entire internal structure of the cilium or flagellum, separating it from the external environment. It contains specialized ion channels and receptors that allow the organelle to sense and respond to chemical or physical stimuli.

outer dynein: These are large motor proteins attached to the outer edge of each microtubule doublet. By converting chemical energy from ATP into mechanical work, they facilitate the sliding of adjacent microtubules to create a bending motion.

inner dynein: Similar to their outer counterparts, these motor proteins are located closer to the center of the axoneme. They work in coordination with outer dyneins to precisely control the waveform and frequency of the organelle’s beat.

nexin: This is a flexible protein link that connects adjacent microtubule doublets to one another. It prevents the microtubules from simply sliding past each other, instead converting that sliding force into the characteristic bending needed for locomotion.

spoke head: This is the widened terminal end of the radial spoke that sits in close proximity to the central sheath. It acts as a signaling interface between the central microtubules and the outer doublets to coordinate complex movement patterns.

radial spoke: These are protein structures that extend from each of the nine outer doublets inward toward the central pair of microtubules. They play a critical role in the structural integrity of the axoneme and the transmission of regulatory signals.

subfiber B: This refers to the incomplete, C-shaped microtubule that is fused to subfiber A in an outer doublet. It shares a portion of its wall with its partner fiber, a configuration that is essential for the stability of the doublet structure.

subfiber A: This is the complete, circular microtubule within each outer doublet that contains 13 protofilaments. It serves as the primary attachment site for dynein arms and radial spokes, acting as the structural anchor for the doublet.

triplet centriole: This arrangement consists of nine sets of three microtubules organized into a ring, found within the basal body. It serves as the fundamental organizing center from which the doublet microtubules of the cilium or flagellum grow.

basal body: This is a specialized structure at the base of a cilium or flagellum that anchors it to the cell’s cytoskeleton. It is derived from a centriole and is necessary for the proper assembly and orientation of the motile organelle.

flagella: These are long, whip-like appendages typically found in small numbers on a cell, such as those used for the locomotion of the parasite Trichomonas vaginalis. They move with an undulating, wave-like motion to propel the cell through fluid environments.

cilia: These are short, hair-like projections that often cover the surface of a cell in large numbers. In protozoans like Paramecium, they are used both for movement and for sweeping food particles into the organism’s oral cavity.

mouth: Also known as a cytostome, this is a specialized opening in certain protozoans used for the ingestion of nutrients. Ciliary action creates currents that direct microorganisms and organic debris into this opening for digestion.

The Axoneme: The Mechanical Heart of Motility

The internal architecture of cilia and flagella is one of the most remarkable examples of biological engineering. At the core of these structures is the axoneme, a specialized cytoskeleton composed of microtubules and associated motor proteins. The “9+2” pattern—nine outer doublets surrounding two central singlets—is a universal blueprint found across diverse life forms, from microscopic protozoans to human specialized tissues. This structural consistency is vital for generating the rhythmic, high-frequency movements required for survival.

Microtubules within the axoneme are dynamic polymers of tubulin that provide both rigidity and a track for molecular motors. The motion of these organelles is not a simple contraction; rather, it is driven by the coordinated sliding of microtubules relative to one another. This sliding is translated into a bend by the restrictive links of nexin, creating the characteristic “power stroke” and “recovery stroke” seen in ciliated tissues.

Key aspects of ciliary and flagellar function include:

- Conversion of ATP energy into mechanical work via dynein proteins.

- Coordination of beat patterns through radial spoke and central pair interactions.

- Anchoring and template formation provided by the basal body.

- Sensory transduction where the organelle acts as a cellular antenna.

Clinical Focus: Trichomoniasis and Flagellated Pathogens

Understanding flagellar structure is clinically significant when examining parasites like Trichomonas vaginalis. This flagellated protozoan is the causative agent of Trichomoniasis, one of the most common non-viral sexually transmitted infections (STIs) globally. The parasite utilizes its four anterior flagella and one posterior flagellum to move through the urogenital tract, allowing it to adhere to epithelial cells and cause localized inflammation.

In women, the infection typically manifests as vaginitis, characterized by a frothy, foul-smelling yellow-green discharge, vulvovaginal irritation, and dysuria. Medical examination may reveal a “strawberry cervix,” which refers to punctate hemorrhages on the cervical wall. In men, the infection is often asymptomatic but can lead to urethritis or prostatitis. Because the parasite relies on its motility to colonize and damage the host tissue, the study of its flagellar mechanics is a focal point for developing new antimicrobial strategies.

Diagnosis usually involves microscopic examination of a wet mount to observe the characteristic “jerky” motility of the trophozoites or through highly sensitive nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). Treatment is typically straightforward, involving a single dose of nitroimidazole antibiotics like metronidazole or tinidazole. However, both partners must be treated simultaneously to prevent reinfection and the further spread of the parasite.

The physiological study of cilia also extends to human genetic conditions known as primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). In these patients, mutations in dynein arms or other axonemal proteins result in immotile cilia. This leads to chronic respiratory infections, as the body cannot effectively clear mucus, and can also cause infertility due to impaired sperm motility or fallopian tube transport. This highlights the vital importance of the 9+2 microtubule array in maintaining human health across multiple organ systems.