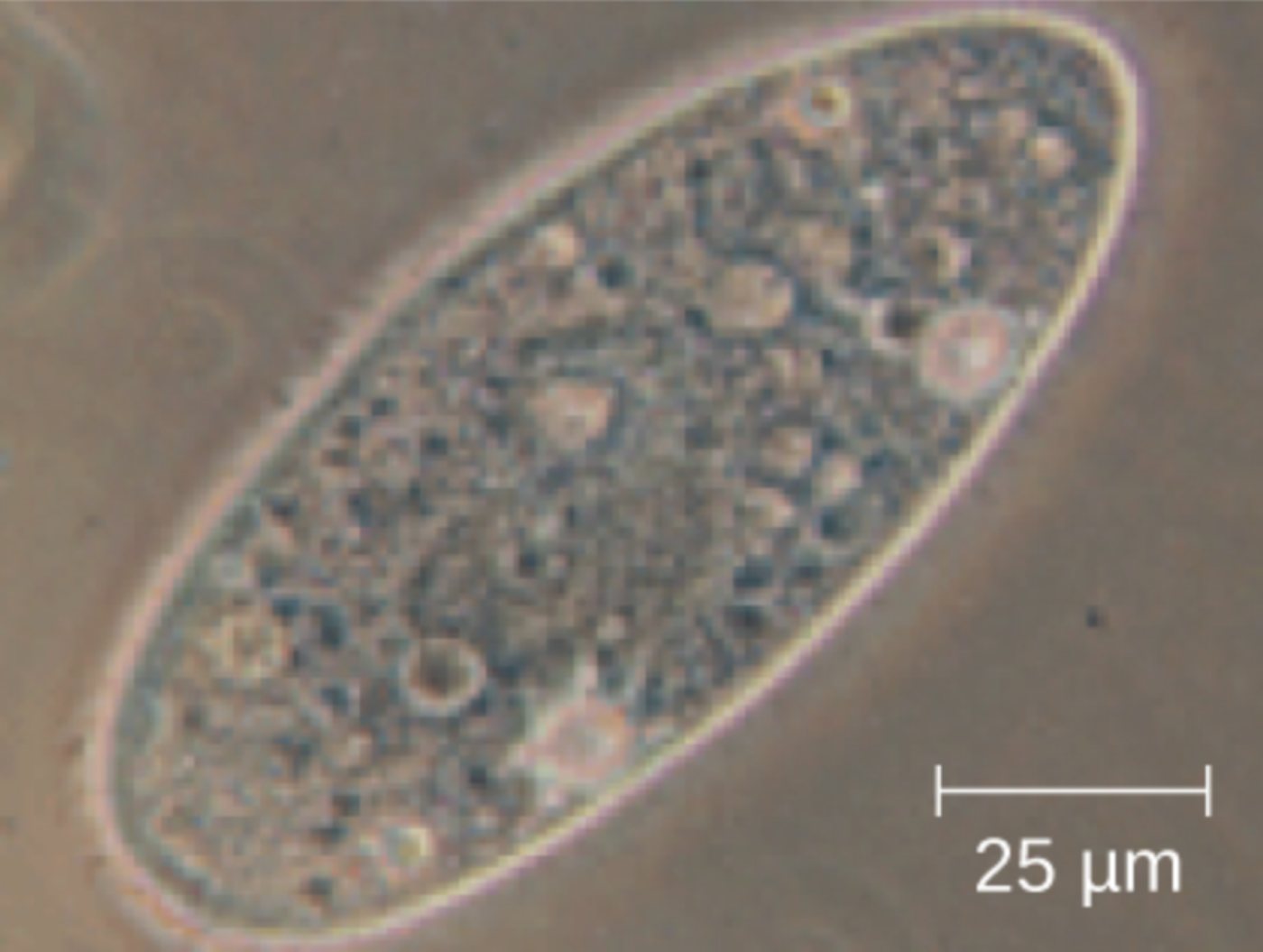

Eukaryotic life manifests in a staggering variety of forms, each adapted to survive and thrive in specific ecological niches. The Paramecium, a genus of unicellular ciliates, serves as a primary model for understanding how complex anatomical and physiological systems can exist within a single cell. By examining its distinct ovoid shape and the specialized organelles that drive its movement and metabolism, we gain deeper insight into the foundational principles of microbiology and cellular health.

25 μm: This label represents a scale bar indicating a distance of twenty-five micrometers. It is a critical reference tool used in microscopy to provide an accurate sense of the organism’s physical dimensions and the magnification level of the image.

The Significance of Cellular Diversity and Morphology

The study of cellular morphology is essential for understanding how structure dictates function at the microscopic level. Eukaryotic cells, characterized by their membrane-bound organelles and complex genetic material, exhibit diverse shapes ranging from the elongated neurons of the human body to the streamlined, ovoid forms of aquatic protozoa. These shapes are not arbitrary; they are evolutionary adaptations that optimize the cell’s ability to move, consume nutrients, and interact with its environment.

Among the various forms found in the eukaryotic domain, the ovoid or slipper-like shape of the Paramecium is particularly efficient for locomotion in fluid environments. This genus belongs to the phylum Ciliophora, a group defined by the presence of thousands of hair-like projections called cilia. These cilia beat in a coordinated, wave-like fashion, allowing the cell to navigate through water with remarkable precision and speed.

Key features of the Paramecium include:

- A protective, flexible outer membrane known as the pellicle.

- Thousands of cilia used for both locomotion and feeding.

- A specialized oral groove that directs food particles into the cell.

- Contractile vacuoles that manage internal water pressure and waste.

- A dual-nuclear system consisting of a macronucleus and a micronucleus.

Physiologically, these single-celled organisms perform complex tasks that are analogous to the organ systems of multicellular animals. They must maintain a stable internal environment, process energy, and reproduce. The ability of a single cell to coordinate these varied functions demonstrates the incredible efficiency of eukaryotic cellular architecture and provides a blueprint for understanding more complex biological systems.

Anatomical Specializations of the Ciliate Form

The “ovoid” designation of the Paramecium refers to its rounded, egg-like silhouette, which is tapered at the ends to reduce drag during movement. Beneath the plasma membrane lies the pellicle, a structured layer that maintains the cell’s shape while providing enough flexibility for the organism to squeeze through narrow spaces. This structural integrity is supported by a complex cytoskeleton composed of microtubules and microfilaments, which also serve as the tracks for internal organelle transport.

One of the most prominent anatomical features is the oral groove, a depression on the side of the cell. Cilia lining this groove create a localized current that draws bacteria and small organic particles toward the cytostome, or “cell mouth.” Once ingested, the food is packaged into food vacuoles that circulate through the cytoplasm via a process called cyclosis. During this journey, digestive enzymes break down the contents, and the nutrients are absorbed directly into the surrounding fluid.

Physiological Regulation and Genetic Management

Maintaining homeostasis is a significant challenge for a cell living in a freshwater environment, where water constantly enters the cell via osmosis. To prevent the cell from bursting, the Paramecium utilizes specialized organelles called contractile vacuoles. These structures act as bilge pumps, collecting excess water from the cytoplasm and forcefully expelling it through a pore in the pellicle. This active transport mechanism is a vital physiological process that requires a constant supply of energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

The genetic organization of the Paramecium is equally unique, featuring nuclear dimorphism. The large macronucleus handles the day-to-day metabolic functions and protein synthesis required for survival. In contrast, the smaller micronucleus contains the “germline” DNA used during conjugation, a form of genetic recombination that occurs between two individuals. This separation of duties allows the cell to maintain high metabolic activity while ensuring the long-term survival and diversity of the species through sexual reproduction.

By observing these organisms, researchers can study the fundamental mechanics of life, from the way cilia interact with fluid dynamics to the complex signaling pathways that coordinate vacuole contractions. The Paramecium remains one of the most studied eukaryotes in biology, providing a window into the ancient evolutionary history of complex cells and the sophisticated mechanisms that allow them to function as independent living units.

The diverse morphologies of eukaryotic cells represent nature’s ingenuity in solving the problems of survival at the microscopic scale. Whether it is the ovoid shape of a pond-dwelling ciliate or the specialized structures of human tissue cells, the relationship between form and function is a cornerstone of modern biological science. Understanding these cellular blueprints is essential for advancements in medicine, biotechnology, and our broader comprehension of the living world.