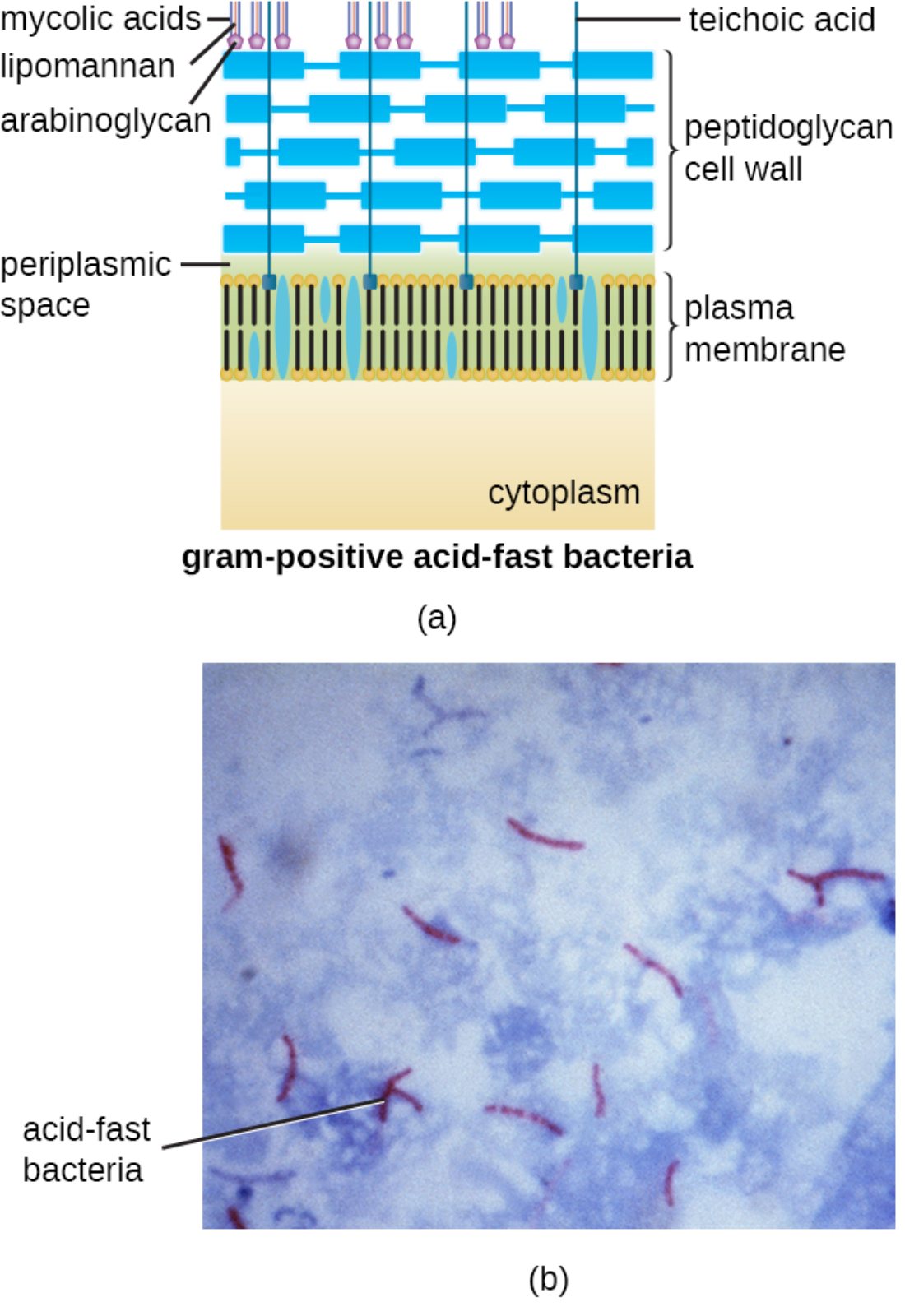

Acid-fast bacteria possess a highly specialized cell wall structure that distinguishes them from typical Gram-positive organisms. By incorporating a thick layer of waxy mycolic acids, these pathogens, particularly members of the Mycobacteriaceae family, develop a formidable defense against environmental stress and pharmacological agents. Understanding this anatomy is essential for diagnosing serious infections such as tuberculosis and leprosy.

mycolic acids: These are long-chain fatty acids that create a waxy, hydrophobic layer on the exterior of the cell wall. This layer prevents dehydration and acts as a chemical barrier against many common antibiotics and disinfectants.

lipomannan: This is a major lipoglycan molecule found in the cell wall of mycobacteria that is anchored to the plasma membrane. It plays a significant role in modulating the host immune response and is essential for bacterial viability.

arabinoglycan: This polymer serves as the structural link between the internal peptidoglycan layer and the outer mycolic acids. It is a critical target for certain anti-tubercular drugs, such as ethambutol, which inhibit its synthesis and weaken the cell wall.

teichoic acid: These acidic polymers are typically associated with Gram-positive bacteria and contribute to the structural integrity of the cell wall. They also aid in sequestering metal ions and play a role in cell-to-cell signaling and attachment.

peptidoglycan cell wall: This is a polymer consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer outside the plasma membrane. It provides the necessary tensile strength to maintain the cell’s shape and resist osmotic pressure.

periplasmic space: This is the compartment located between the inner cytoplasmic membrane and the peptidoglycan cell wall. It contains various proteins and enzymes that facilitate nutrient acquisition and metabolic regulation.

plasma membrane: This phospholipid bilayer encloses the cytoplasm and exhibits selective permeability to regulate the movement of substances. It is also the site for energy production and lipid synthesis within the bacterial cell.

cytoplasm: This is the jelly-like substance inside the cell membrane that contains the bacterial genome, ribosomes, and metabolic intermediates. It serves as the primary site for cellular growth, replication, and protein production.

acid-fast bacteria: These are organisms characterized by their ability to resist decolorization by acid-alcohol during laboratory staining procedures. This property is due to the high lipid content in their cell walls, which traps specialized dyes.

The Significance of the Waxy Microbial Envelope

The classification of bacteria often begins with the Gram stain; however, a specific subset of organisms remains elusive to this traditional method. Acid-fast bacteria, most notably the genus Mycobacterium, are technically Gram-positive but possess a unique chemical composition that prevents standard dyes from penetrating. The presence of a waxy envelope makes these cells exceptionally hardy and difficult to treat, requiring specialized staining techniques and prolonged antibiotic regimens.

This structural complexity is what allows these bacteria to survive inside host macrophages, the very immune cells meant to destroy them. The interplay between the peptidoglycan base and the outer lipid layers creates a wall that is nearly impermeable to water-soluble agents. This physical defense is a primary driver of the chronic nature of the diseases they cause.

Key characteristics of acid-fast bacteria include:

- High concentrations of waxy mycolic acid within the cell wall.

- Resistance to decolorization by acidic solutions after primary staining.

- A slow growth rate compared to other bacterial species due to high metabolic energy demands.

- The ability to persist in harsh environments, including survival within host immune cells.

By understanding the physiological hurdles presented by this structure, medical professionals can better tailor treatments. The slow diffusion of nutrients through the waxy layer directly correlates to the long incubation periods observed in associated clinical conditions.

Pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

The most clinically significant acid-fast pathogen is mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB). When a person inhales aerosolized droplets containing MTB, the bacteria enter the lungs and are engulfed by alveolar macrophages. Instead of being destroyed, the bacteria use their specialized cell wall to prevent the fusion of lysosomes with the phagosome, allowing them to replicate intracellularly.

TB primarily affects the respiratory system but can spread to the kidneys, spine, and brain. Clinical symptoms often include a persistent cough lasting more than three weeks, chest pain, coughing up blood, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss. The body’s attempt to wall off the infection results in the formation of granulomas, or tubercles, which can lead to permanent lung tissue scarring and respiratory failure if left untreated.

Clinical Staining and Laboratory Diagnosis

Diagnosing these infections requires the Ziehl-Neelsen stain or the Kinyoun (cold) stain. During the Ziehl-Neelsen process, heat or high concentrations of detergent are used to force the red dye, carbolfuchsin, through the hydrophobic waxy cell wall. Once the dye has penetrated, it remains resistant to removal by acid-alcohol decolorizers.

Under the microscope, acid-fast cells appear as bright red, rod-shaped structures against a blue background, which is provided by a methylene blue counterstain. This microscopic identification is a critical step in infectious disease management, allowing for the rapid initiation of the complex multidrug therapy required to cure the patient and prevent community transmission.

The unique architecture of acid-fast bacteria illustrates the incredible adaptability of microbial life. From the foundational plasma membrane to the protective waxy shield of mycolic acids, every layer of the cell envelope is optimized for survival under host-induced pressure. Understanding these structures not only aids in laboratory diagnosis but also guides the development of pharmaceutical agents designed to breach these formidable defenses and improve patient outcomes worldwide.