Electron microscopy represents a pivotal advancement in diagnostic medicine and biological research, allowing scientists to visualize structures significantly smaller than the limits of visible light. By utilizing accelerated electron beams instead of photons, these instruments provide unparalleled insights into the cellular and molecular world. The following guide details the distinct components and operational differences between the Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) and the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), illuminating how each system contributes to the understanding of human anatomy and pathology.

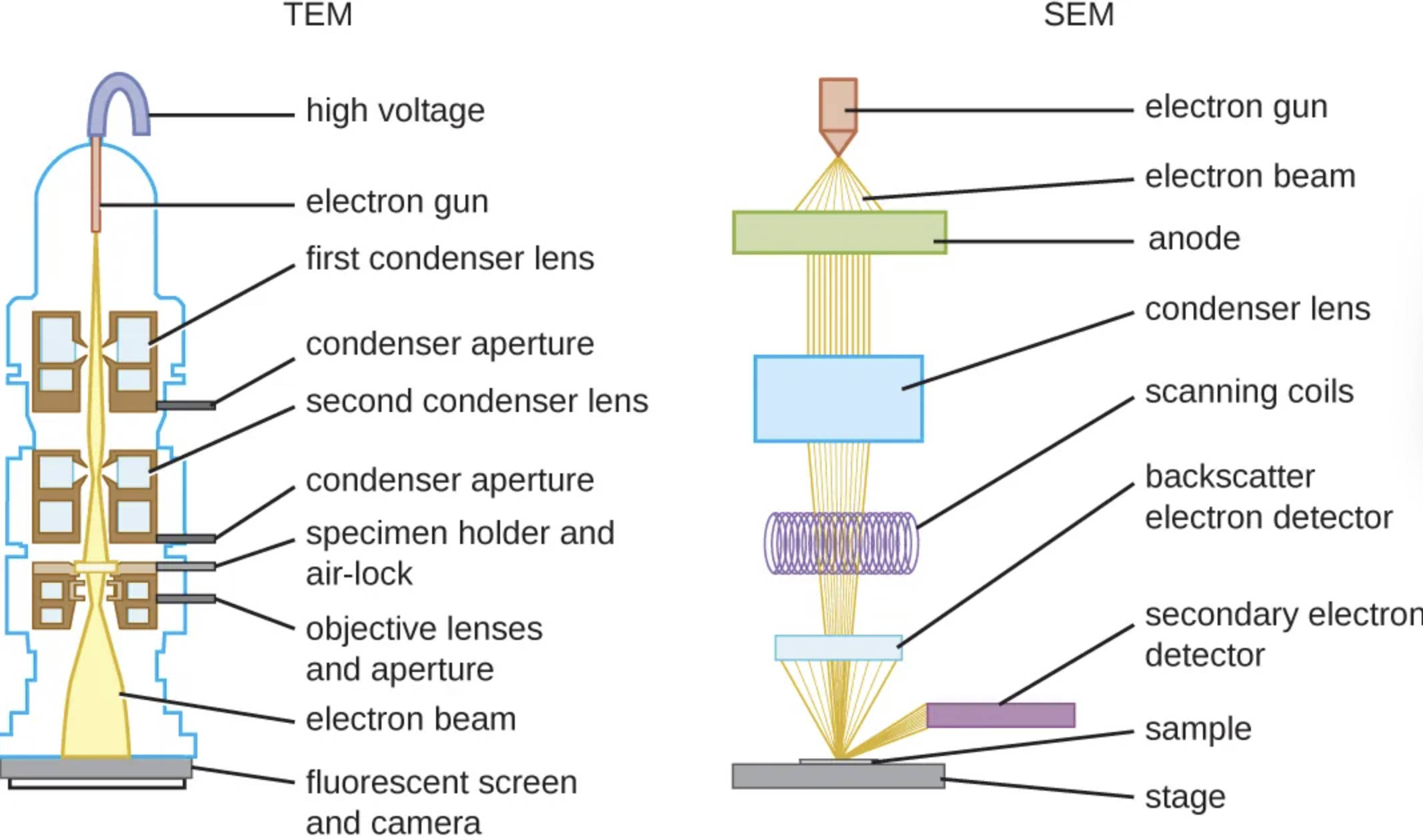

High voltage: Located at the very top of the TEM column, this component generates the electrical potential difference required to accelerate electrons to extremely high speeds. The resulting high-energy beam is necessary to create a wavelength short enough to pass through the specimen and resolve nanometer-scale details.

Electron gun (TEM): This is the source of the illumination, typically consisting of a tungsten filament or a crystal source that emits a stream of electrons when heated. It sits within the vacuum column and directs the initial stream of particles downward toward the electromagnetic lenses.

First condenser lens: This electromagnetic lens is the initial focusing element that shapes the electron beam as it leaves the gun. It controls the spot size of the beam, effectively determining how much illumination eventually reaches the specimen.

Condenser aperture (TEM): Located beneath the first lens, this metal strip contains a tiny hole that restricts the electron beam. By blocking off-axis or scattered electrons, it ensures that only a coherent, central beam continues down the column, which improves image clarity and contrast.

Second condenser lens: Working in tandem with the first lens and aperture, this component further refines and focuses the beam onto the specimen. It allows the operator to adjust the intensity and convergence of the light on the specific area of the tissue being examined.

Specimen holder and air-lock: This mechanism allows for the insertion of the delicate, ultra-thin biological sample into the high-vacuum environment of the microscope column without breaking the vacuum. The holder secures the sample grid in the precise optical path of the electron beam.

Objective lenses and aperture: These are the most critical lenses in the TEM system, responsible for the primary magnification and focusing of the image after the beam passes through the specimen. The quality and stability of these electromagnetic lenses largely determine the final resolution of the internal cellular structures.

Electron beam (TEM): This is the concentrated stream of high-energy particles that travels down the entire length of the column. In TEM, this beam passes directly through the translucent specimen to form a shadow-image based on the density of the internal structures.

Fluorescent screen and camera: Situated at the base of the TEM column, this component captures the final image. The electrons hit a phosphorescent screen that glows to create a visible image for the user, while a digital camera records the projection for analysis and diagnostic reporting.

Electron gun (SEM): Similar to the TEM, this component acts as the source of electrons at the top of the SEM column. It emits the primary electrons that will eventually be focused into a fine probe to scan the surface of the sample.

Electron beam (SEM): This stream of electrons travels downward but, unlike in TEM, is focused into a tight point rather than a broad beam. It is manipulated to interact with the surface of the sample rather than passing through it.

Anode: This positively charged plate accelerates the electrons coming from the gun, pulling them down the column with significant force. The potential difference created by the anode determines the energy of the electrons landing on the sample.

Condenser lens (SEM): These electromagnetic lenses reduce the diameter of the electron beam. By demagnifying the beam, they create a very fine, sharp probe that is essential for achieving high-resolution surface imaging.

Scanning coils: These electromagnetic coils are the defining feature of the SEM, distinguishing it from the TEM. They rapidly deflect the electron beam back and forth in a raster pattern (line by line) across the surface of the specimen, synchronizing with the display monitor.

Backscatter electron detector: This sensor detects high-energy electrons that bounce directly off the sample’s atoms. The intensity of backscattered electrons is often related to the atomic number of the elements in the sample, helping researchers distinguish between different chemical compositions in a tissue.

Secondary electron detector: This detector captures low-energy electrons that are ejected from the very surface of the specimen’s atoms during the scan. These signals are primarily used to create the detailed, 3D-appearing topographical images characteristic of SEM.

Sample: In SEM, the specimen does not need to be ultra-thin; it can be a bulkier object like a blood cell, a biopsy surface, or a bacterial colony. The sample is usually coated with a thin layer of conductive metal, such as gold, to prevent charge buildup.

Stage: This is the platform where the SEM sample is mounted. It is highly mechanically stable and can often be tilted or rotated to allow the user to view the specimen’s surface features from multiple angles.

Medical Applications and Structural Analysis

The division between Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) usage in medicine is defined by what the clinician needs to see: the inside or the outside. TEM is analogous to a highly advanced X-ray; it looks through a specimen. In clinical pathology, TEM is indispensable for renal biopsies. For instance, in conditions like membranous nephropathy, pathologists use TEM to observe the glomerular basement membrane and identify immune complex deposits that are invisible to standard light microscopy. The technique requires the tissue to be embedded in plastic resin and sliced into sections less than 100 nanometers thick—thinner than a single bacterium.

Conversely, SEM is used to study surface topography. It creates images that appear three-dimensional, providing data on the texture, shape, and arrangement of cells. In hematology, SEM can be used to examine the morphology of erythrocytes (red blood cells). For example, it can clearly differentiate between the smooth, biconcave shape of a healthy cell and the spiky, distorted shape of an acanthocyte found in liver disease. While SEM offers lower resolution regarding internal organelles compared to TEM, its ability to image bulk samples without complex sectioning makes it unique.

The fundamental difference lies in the signal formation. TEM relies on the electron beam transmitting through the sample, where denser structures (like the nucleolus or mitochondria) scatter electrons and appear darker. SEM relies on the beam exciting the surface of the sample to emit secondary electrons. These signals are collected to build a map of the surface. This distinction dictates their use cases in research; TEM is vital for virology to see the internal RNA/DNA core of a virus, whereas SEM is used to visualize the external spike proteins on the viral shell.

Key distinctions between these two modalities include:

- Image Formation: TEM produces 2D projection images of internal structure; SEM produces 3D-like images of surface topography.

- Sample Preparation: TEM requires laborious ultra-thin sectioning; SEM requires conductive coating but allows for bulkier samples.

- Resolution: TEM generally achieves higher resolution (atomic scale) compared to SEM.

- Medical Focus: TEM is used for intracellular diagnosis (organelles); SEM is used for cell surface and tissue architecture analysis.

Conclusion

Both Transmission and Scanning Electron Microscopes are cornerstones of modern biomedical imaging, though they serve complementary roles. The TEM allows pathologists to peer deep inside the cell to diagnose metabolic and genetic disorders affecting organelles, while the SEM provides the topographical context needed to understand complex tissue interactions and cell shapes. Together, these technologies bridge the gap between gross anatomy and molecular biology, enabling precise diagnoses and advancing our understanding of disease mechanisms at the nanoscopic level.