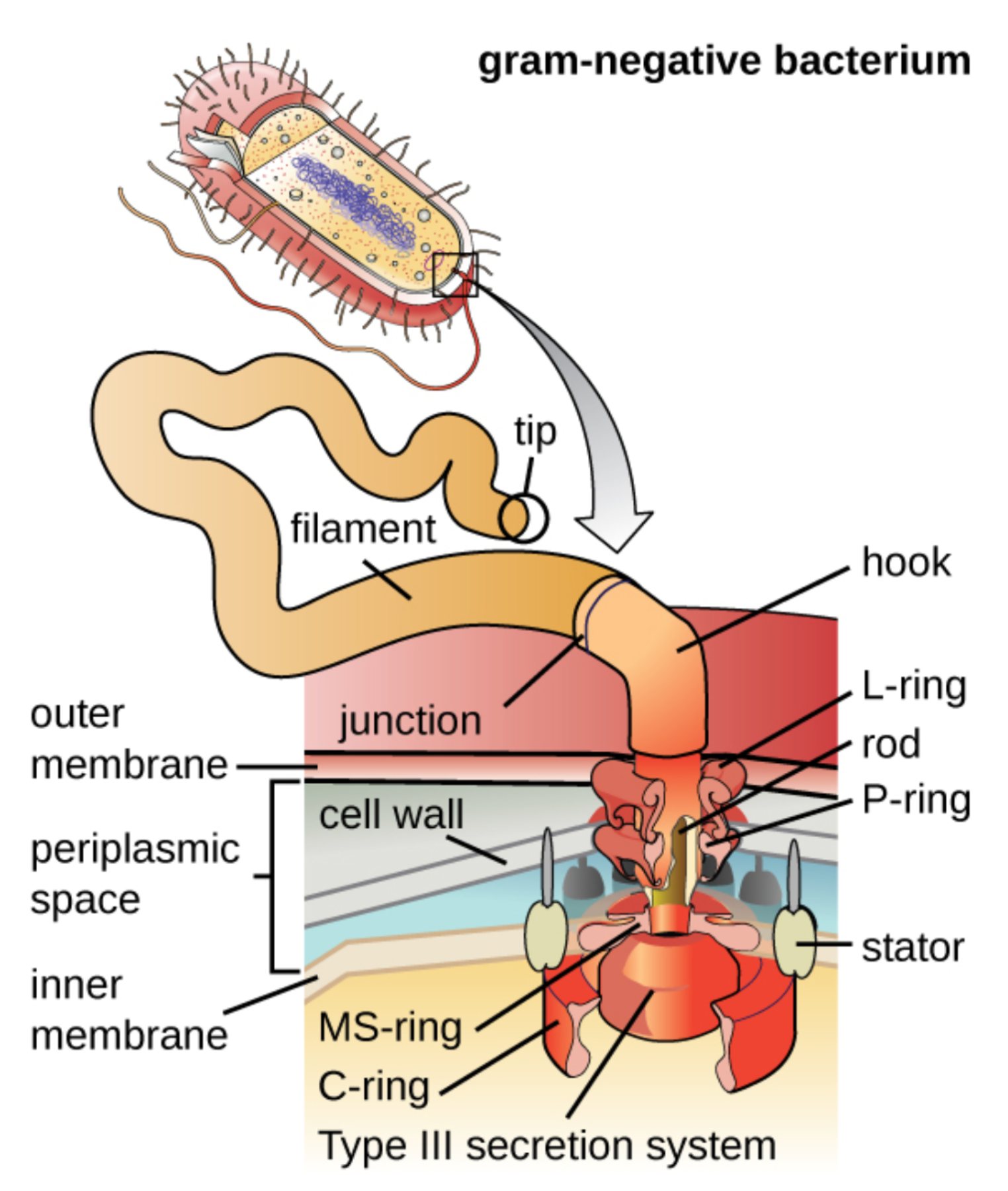

The bacterial flagellum is a marvel of biological nanotechnology, serving as a complex rotary motor that propels microbes through their aqueous environments. In Gram-negative bacteria, this apparatus is specifically engineered to span two separate membranes and a thin cell wall, providing the motive force necessary for colonization and survival. Understanding the intricate arrangement of these protein assemblies allows clinicians and researchers to better comprehend bacterial pathogenesis and the mechanisms behind microbial locomotion.

tip: This is the specialized protein cap located at the very end of the flagellar propeller. It is essential for the assembly process, as it guides the incorporation of flagellin subunits as they are exported from the cell.

filament: The filament is a long, rigid, whip-like structure composed of thousands of repeating protein subunits. It functions as a biological propeller, rotating at high speeds to drive the bacterium forward in its environment.

junction: This transitional region represents the connection point where the rigid external filament attaches to the flexible hook. It ensures that rotational energy is transmitted smoothly from the internal motor to the propeller.

hook: The hook is a short, curved protein segment that acts as a universal joint between the filament and the basal body. It allows the torque generated by the cytoplasmic motor to be converted into the circular motion of the external propeller.

outer membrane: This is the external lipid bilayer characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria, containing lipopolysaccharides that act as a barrier. The flagellar motor must pass through this layer, requiring specialized structural rings for stability.

L-ring: Located within the outer membrane, the L-ring (lipopolysaccharide ring) serves as a bushing for the rotating central rod. It ensures the rod can spin freely without damaging the integrity of the outer lipid layer.

rod: The rod is a central proteinaceous axle that passes through the rings of the basal body. It serves as the primary transmission shaft, transferring mechanical energy from the inner rotor to the external hook and filament.

cell wall: In Gram-negative bacteria, the cell wall consists of a thin layer of peptidoglycan located within the periplasmic space. This layer provides structural scaffolding for the P-ring of the flagellar assembly.

P-ring: The P-ring is anchored within the peptidoglycan cell wall and functions as a secondary bushing for the central rod. It provides lateral support to the rotating axle as it exits the cell’s interior compartments.

periplasmic space: This is the aqueous region located between the inner and outer membranes of the Gram-negative cell. It houses the P-ring and provides the environment through which the central rod must travel.

inner membrane: Often referred to as the cytoplasmic membrane, this phospholipid bilayer is the foundation of the flagellar motor. It maintains the electrochemical gradient required to power the rotation of the entire apparatus.

MS-ring: The MS-ring (membrane/supramembrane ring) is embedded directly into the inner membrane of the bacterium. It serves as the structural base for the rotor assembly and helps anchor the motor proteins.

stator: These are stationary protein complexes that surround the rotor in the inner membrane and generate torque. They harness energy from the proton motive force to turn the rotor, much like an electric motor uses magnetic fields.

C-ring: The C-ring, or cytoplasmic ring, is located on the interior face of the inner membrane and functions as a switch complex. It is responsible for changing the direction of flagellar rotation in response to sensory signals.

Type III secretion system: This specialized apparatus at the base of the flagellum is responsible for exporting structural proteins through the hollow center of the rod. It allows the flagellum to grow from the tip by pumping out building blocks synthesized in the cytoplasm.

The Mechanical Logic of Microbial Locomotion

The bacterial flagellum is one of the most sophisticated examples of molecular machinery found in nature. Unlike eukaryotic flagella, which function through a sliding filament mechanism, the bacterial flagellum is a true rotary engine. Gram-negative bacteria possess a particularly complex basal body because the motor must span an extra lipid bilayer compared to Gram-positive species. This ensures that the cell remains watertight and structurally sound even while a high-speed axle rotates through its surface.

This motility is not random; it is guided by a sensory system known as chemotaxis. By sensing chemical gradients in their environment, bacteria can bias their movement toward favorable nutrients and away from toxic substances. This is achieved by the switch complex at the base of the flagellum, which can flip the motor’s rotation between clockwise and counter-clockwise in a fraction of a second, causing the cell to either “run” in a straight line or “tumble” to change direction.

Key anatomical components of the flagellar system include:

- The external filament, composed of repeating subunits of the protein flagellin.

- A basal body consisting of several rings (L, P, MS, and C) that act as bearings and rotors.

- A cytoplasmic switch complex that manages the direction of rotation.

- An export apparatus that facilitates “inside-out” construction of the structure.

The energy for this movement is derived from the flow of ions—typically protons or sodium ions—across the inner membrane. This ion flow through the stator proteins induces conformational changes that push against the rotor, creating the mechanical torque necessary to propel the cell through relatively viscous biological fluids.

Physiology and the Mechanics of Infection

In medical microbiology, the flagellum is recognized as a major component among several virulence factors. Motility allows pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Escherichia coli to swim through mucosal layers and colonize specific tissues, such as the lining of the urinary tract or the intestinal epithelium. Furthermore, the base of the flagellum shares an evolutionary lineage with the “injectisomes” of the Type III Secretion System (T3SS), which virulent bacteria use to pump toxins directly into host cells.

The human immune system has evolved specific receptors to detect these structures. Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) specifically recognizes flagellin, the primary protein component of the filament. When flagellin is detected, it triggers an innate immune response, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines that attempt to neutralize the invading pathogen. This interaction underscores the dual nature of the flagellum: it is both a tool for microbial survival and a marker for host defense.

In summary, the Gram-negative bacterial flagellum is a masterwork of structural biology. From the ion-driven motor in the inner membrane to the flexible hook and rigid external propeller, every component is optimized for speed and directional control. As we continue to investigate the molecular pathways that assemble and power these motors, we gain deeper insights into the fundamental processes of microbial life and the complex interactions between bacteria and their human hosts.