In the microscopic world of prokaryotes, the organization of genetic material is a masterpiece of biological efficiency. Unlike eukaryotic cells, which sequester their DNA within a membrane-bound nucleus, bacteria and archaea utilize a specialized, non-membrane-bound region known as the nucleoid to house their primary genome. This structural arrangement allows for rapid cellular responses and streamlined protein synthesis, making it a critical focus of study in molecular microbiology and genetics.

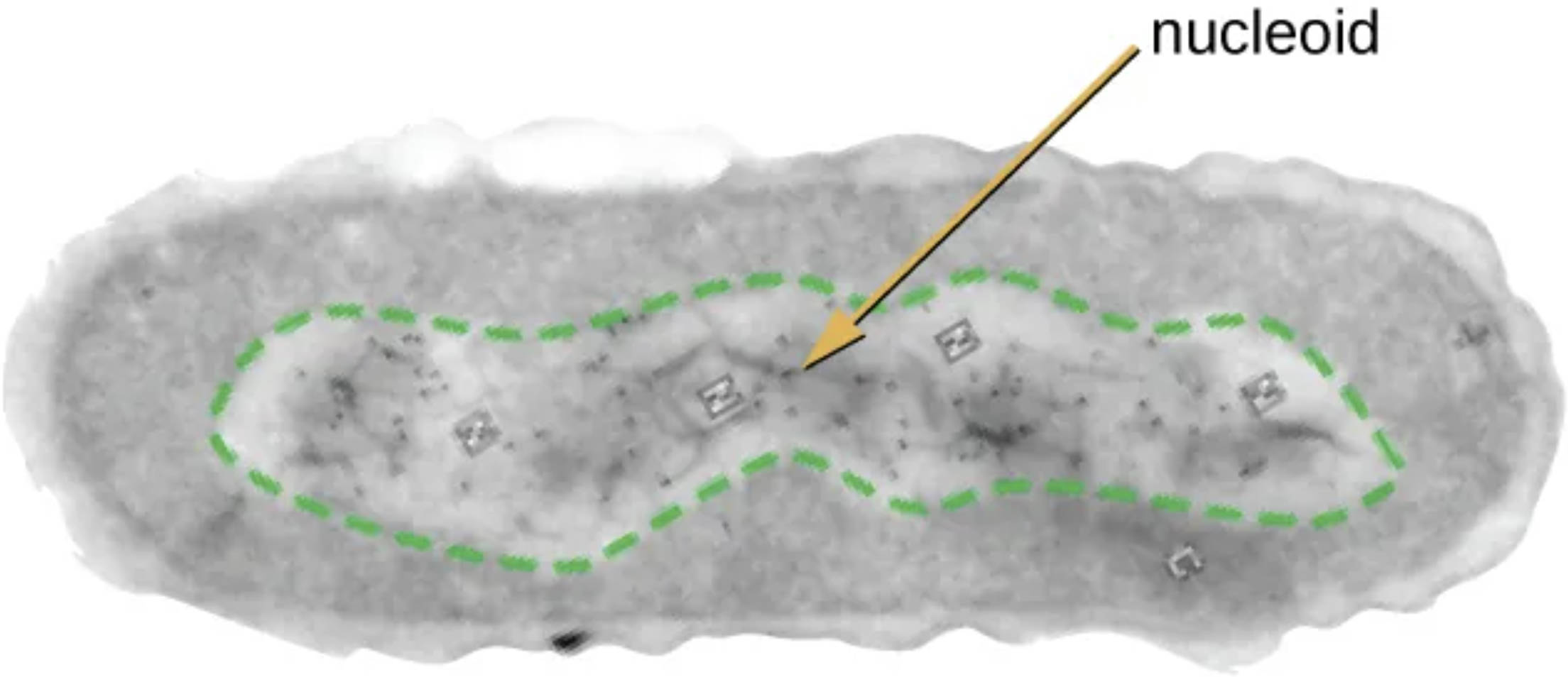

nucleoid: This irregularly shaped region within a prokaryotic cell contains the vast majority of the organism’s genetic material. Because it lacks a surrounding nuclear envelope, the DNA within the nucleoid is in direct contact with the cytoplasm, facilitating the immediate transcription and translation of essential genes.

The internal architecture of a prokaryotic cell is characterized by its simplicity and functionality, with the nucleoid serving as the central hub for genomic information. While the cytoplasm is filled with ribosomes, nutrients, and metabolic enzymes, the nucleoid is specifically reserved for the condensed, circular chromosome. The visualization of this region, often through transmission electron microscopy, reveals a dense area where DNA fibers are tightly packed but remain accessible for cellular processes.

The formation of the nucleoid is not a random occurrence but is carefully managed by a group of specialized molecules known as nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs). These proteins serve a function similar to histones in eukaryotic cells, helping to fold, bridge, and wrap the long strands of DNA into a compact shape that fits within the tiny volume of the cell. This compacting process is vital because, if stretched out, a single bacterial chromosome would be hundreds of times longer than the cell itself.

Several key features define the nature of the prokaryotic nucleoid:

- Lack of a phospholipid bilayer or nuclear envelope.

- Concentration of circular DNA and DNA-associated proteins.

- Coupling of transcription and translation within the same spatial compartment.

- Dynamic structural changes in response to environmental stressors or growth phases.

Beyond its role as a storage site for DNA, the nucleoid is a highly active physiological structure. It expands and contracts based on the metabolic state of the cell, ensuring that genes required for survival are always positioned for easy access by RNA polymerase. This spatial organization is a fundamental aspect of genomic architecture, providing the structural framework necessary for life in the single-celled domain.

Structural Anatomy and the Role of Supercoiling

The anatomy of the nucleoid is defined by a process known as supercoiling, which involves the twisting of the DNA molecule upon itself to save space. This mechanical tension is regulated by enzymes called topoisomerases, which can add or remove twists to allow the DNA to be opened up for replication or gene expression. The level of supercoiling is highly sensitive to the cell’s internal environment, reflecting the organism’s overall health and energy levels.

The physical boundaries of the nucleoid are maintained through the exclusion of larger structures like ribosomes from the dense DNA mass. This “macromolecular crowding” helps keep the genetic material concentrated in the center of the cell while allowing smaller molecules, such as nucleotides and transcription factors, to diffuse freely in and out. This creates a semi-distinct functional zone without the need for a physical membrane barrier.

Physiological Functions and Cellular Replication

Physiologically, the nucleoid must remain highly organized during the rapid process of binary fission. As the cell prepares to divide, the circular DNA is replicated, and the two resulting chromosomes are carefully segregated to opposite poles of the cell. This ensures that each daughter cell receives a complete and accurate copy of the genetic blueprint. The coordination between DNA replication and the physical growth of the cell membrane is a hallmark of prokaryotic efficiency.

Furthermore, the lack of a nuclear membrane allows for “coupled transcription-translation.” This means that as soon as an mRNA strand is synthesized from the DNA template in the nucleoid, ribosomes can immediately attach to it and begin building proteins. This instantaneous link between the genome and the proteome allows prokaryotes to adapt to new environments—such as a change in temperature or the presence of an antibiotic—with incredible speed.

The study of the nucleoid region provides essential insights into the fundamental mechanics of life. By understanding how bacteria organize their DNA without a nucleus, researchers can develop new strategies for combating pathogens or engineering microbes for industrial applications. The nucleoid stands as a testament to the fact that even without complex internal membranes, prokaryotic cells possess a highly sophisticated and orderly system for managing the most critical molecule in existence.