Explore the intricate anatomy and dual functionality of the pancreas, a vital organ expertly orchestrating both exocrine digestion and endocrine hormone secretion. This article delves into its distinct regions—head, body, and tail—and examines the specialized cellular structures, including acinar cells and pancreatic islets, highlighting their critical contributions to nutrient breakdown, blood sugar regulation, and overall metabolic health.

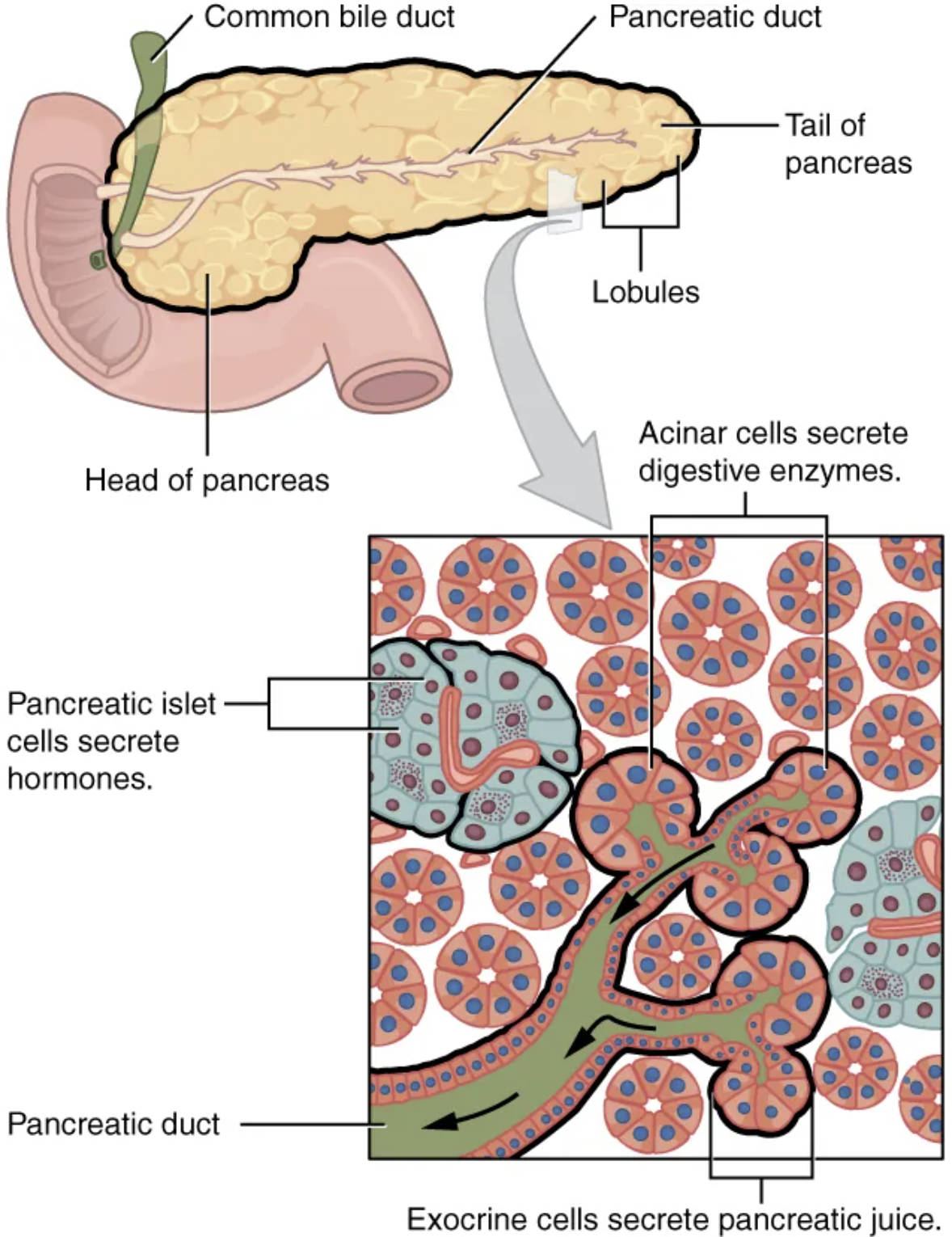

Common bile duct: This duct carries bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, to the duodenum. It typically joins with the pancreatic duct to deliver its contents, aiding in fat emulsification and digestion.

Pancreatic duct: Also known as the duct of Wirsung, this is the main duct that runs the length of the pancreas. It collects pancreatic juice, a mixture of digestive enzymes and bicarbonate, and delivers it to the duodenum for chemical digestion.

Tail of pancreas: This is the slender, left-most portion of the pancreas, extending towards the spleen. It is generally rich in pancreatic islets, contributing significantly to the organ’s endocrine function.

Lobules: These are small, functional subdivisions within the pancreas, each containing a cluster of acinar cells and a network of small ducts. The lobular structure organizes the exocrine secretory units of the pancreas.

Head of pancreas: This is the widest part of the pancreas, located within the C-shaped curve of the duodenum. It houses numerous acinar cells and is a common site for pancreatic diseases, including pancreatic cancer.

Acinar cells secrete digestive enzymes: These exocrine cells are organized into grape-like clusters called acini, which constitute the bulk of the pancreas. Their primary function is to synthesize and secrete potent digestive enzymes, such as amylase, lipase, and proteases, into the pancreatic duct system.

Pancreatic islet cells secrete hormones: Also known as islets of Langerhans, these are clusters of endocrine cells scattered throughout the exocrine pancreas. These cells secrete vital hormones directly into the bloodstream, including insulin and glucagon, which regulate blood glucose levels.

Exocrine cells secrete pancreatic juice: This general label refers collectively to the acinar cells and the duct cells of the pancreas. Acinar cells produce digestive enzymes, while duct cells produce bicarbonate-rich fluid, both components essential for the pancreatic juice delivered to the duodenum.

The pancreas is a truly remarkable organ, unique in its capacity to serve both as a digestive exocrine gland and an endocrine gland regulating metabolism. Located posterior to the stomach, this elongated, glandular organ is indispensable for the breakdown of food in the small intestine and for maintaining stable blood glucose levels throughout the body. Its dual functionality underscores its critical importance in human physiology, influencing everything from nutrient absorption to energy homeostasis.

Anatomically, the pancreas is typically described as having a head, a body, and a tail, each region contributing to its overall function. The head is nestled within the curve of the duodenum, while the tail extends towards the spleen. Microscopically, the pancreas is a fascinating mosaic of two distinct types of tissue: the vast majority dedicated to its exocrine role, producing digestive enzymes, and smaller, specialized clusters responsible for its endocrine functions, secreting hormones.

The coordinated activity of these different cellular components ensures that the body can efficiently digest carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, while simultaneously preventing harmful fluctuations in blood sugar. Disruptions to either the exocrine or endocrine functions of the pancreas can lead to severe health consequences, highlighting the delicate balance it maintains. The diagram above beautifully illustrates this dual nature, showcasing both the macroscopic anatomy and the microscopic cellular organization responsible for its vital roles.

Anatomy of the Pancreas

The pancreas is an elongated organ, usually measuring about 15-20 cm in length. It is anatomically divided into three main regions:

- Head of pancreas: This is the widest part of the gland, situated in the C-shaped curve of the duodenum. It is intricately associated with the bile duct and pancreatic duct.

- Body of pancreas: This central section extends transversely across the abdomen.

- Tail of pancreas: This slender, tapered end of the pancreas extends to the hilum of the spleen.

Exocrine Pancreas: The Digestive Powerhouse

The vast majority of pancreatic tissue (about 95%) is dedicated to its exocrine function, which is crucial for digestion. This part of the pancreas is composed of clusters of cells called acinar cells, organized into structures known as lobules.

- Acinar cells: These cells are responsible for synthesizing and secreting a potent blend of digestive enzymes, collectively known as pancreatic enzymes. This includes:

- Pancreatic amylase: For carbohydrate digestion.

- Pancreatic lipase: For fat digestion.

- Proteases (e.g., trypsin, chymotrypsin): For protein digestion.

- These enzymes are secreted in an inactive form (zymogens) to prevent self-digestion of the pancreas and are activated once they reach the duodenum.

- Duct cells: The cells lining the small ducts within the pancreas, which eventually merge into the main pancreatic duct, produce a bicarbonate-rich fluid. This fluid is essential for neutralizing the acidic chyme that enters the duodenum from the stomach, creating an optimal pH environment for the pancreatic digestive enzymes to function.

- Pancreatic duct: This major duct collects the pancreatic juice (enzymes + bicarbonate) from the various lobules and transports it to the duodenum. It typically joins with the common bile duct to form the hepatopancreatic ampulla (ampulla of Vater) before emptying into the duodenum.

Endocrine Pancreas: Regulating Blood Glucose

Scattered throughout the exocrine pancreatic tissue are small clusters of endocrine cells, known as pancreatic islet cells or islets of Langerhans. These cells constitute only about 1-2% of the pancreatic mass but are vital for metabolic regulation.

- Insulin: Produced by beta cells within the islets, insulin is a hormone that lowers blood glucose levels by promoting glucose uptake by cells and its storage as glycogen.

- Glucagon: Secreted by alpha cells, glucagon raises blood glucose levels by stimulating the liver to release stored glucose.

- Somatostatin: Delta cells produce somatostatin, which inhibits the secretion of both insulin and glucagon, as well as other gastrointestinal hormones.

Disruptions to the endocrine function of the pancreas, particularly insulin production, can lead to conditions like diabetes mellitus.

In conclusion, the pancreas is a dual-function gland whose intricate cellular organization allows it to perform indispensable roles in both digestion and metabolic regulation. Its exocrine acinar cells provide the essential enzymes and bicarbonate needed for nutrient breakdown in the small intestine, while its endocrine islet cells meticulously control blood glucose levels through hormone secretion. This remarkable versatility underscores the pancreas’s critical importance in maintaining overall physiological homeostasis and digestive health.