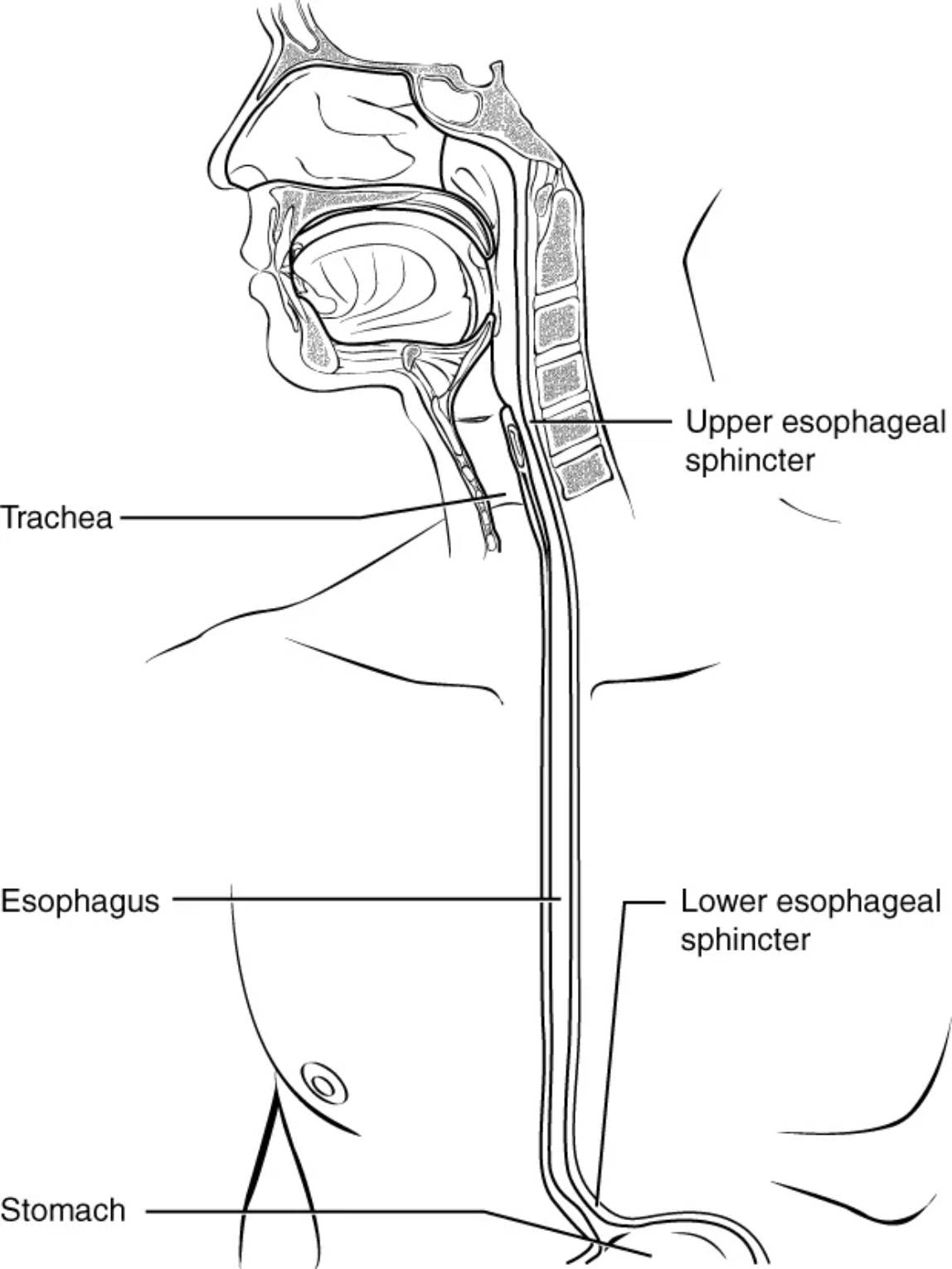

Delve into the esophagus anatomical structure with this detailed diagram, highlighting its role as a muscular tube connecting the pharynx to the stomach. Learn about the crucial upper and lower esophageal sphincters and their precise control over food movement, essential for efficient digestion and preventing reflux.

The esophagus is a vital component of the digestive system, serving as a muscular conduit that efficiently transports food from the pharynx to the stomach. This seemingly simple tube is, in fact, a marvel of coordinated muscular action, ensuring that ingested food moves unidirectionally and safely. Understanding its anatomy, particularly the critical roles of its upper and lower sphincters, is fundamental to comprehending the mechanics of swallowing and the mechanisms that prevent reflux, thereby safeguarding overall digestive health.

Trachea: The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube situated anterior to the esophagus. Its primary function is to provide a clear airway for air to enter and exit the lungs, serving the respiratory system.

Esophagus: The esophagus is a muscular tube, approximately 25-30 cm long in adults, that connects the pharynx to the stomach. Its main role is to propel food and liquids downwards through a series of rhythmic contractions called peristalsis.

Stomach: The stomach is a J-shaped organ located in the upper abdomen, inferior to the esophagus. It acts as a reservoir for food, initiating chemical and mechanical digestion before passing the partially digested chyme into the small intestine.

Upper esophageal sphincter: The upper esophageal sphincter (UES) is a muscular ring located at the superior end of the esophagus, at the junction with the pharynx. It controls the movement of food from the pharynx into the esophagus, relaxing during swallowing to allow passage and contracting at rest to prevent air from entering the esophagus.

Lower esophageal sphincter: The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is a muscular ring situated at the inferior end of the esophagus, where it joins the stomach. It controls the movement of food from the esophagus into the stomach, relaxing during swallowing and contracting at rest to prevent the reflux of stomach contents back into the esophagus.

The Esophagus: A Gateway to Digestion

The esophagus is a remarkable muscular tube, approximately 25-30 centimeters in length, that serves as a critical conduit in the human digestive system. Its primary role is to ensure the efficient and controlled transit of food and liquids from the pharynx to the stomach. Far from being a simple passive tube, the esophagus employs sophisticated muscular contractions and a specialized valve system to achieve this vital function, protecting the airway and initiating the next stages of digestion.

The journey of a swallowed food bolus through the esophagus is a highly coordinated process, managed by:

- Peristalsis: Wave-like muscular contractions that propel food downwards.

- Upper Esophageal Sphincter (UES): Controls entry of food from the pharynx.

- Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES): Regulates food passage into the stomach and prevents reflux.

When we swallow, the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes, allowing the food bolus to enter the esophagus. Immediately, a wave of peristalsis begins, pushing the food downwards. This involuntary muscular action ensures that food moves efficiently, regardless of body position. As the food approaches the stomach, the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes to permit its entry. Crucially, after the food has passed, the LES contracts firmly, acting as a barrier to prevent the acidic contents of the stomach from flowing back into the esophagus.

Dysfunction of either esophageal sphincter can lead to significant health issues. For instance, a weakened or improperly functioning lower esophageal sphincter is a common cause of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), where stomach acid repeatedly flows back into the esophagus, causing heartburn, irritation, and potentially more severe complications over time. Conditions affecting the esophagus itself, such as achalasia (where the LES fails to relax properly) or esophageal spasms, can also impede the passage of food, leading to difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and chest pain. Understanding the precise anatomical and physiological mechanisms of the esophagus and its sphincters is therefore paramount for diagnosing and managing a wide range of digestive disorders.

In conclusion, the esophagus, with its coordinated peristaltic contractions and meticulously controlled sphincters, plays an indispensable role in the digestive process. It is a critical link between ingestion and the subsequent stages of nutrient breakdown. Maintaining the healthy function of this muscular tube and its associated sphincters is essential for preventing discomfort, ensuring efficient food transit, and safeguarding against conditions that can significantly impact a person’s quality of life.