Shewanella is a remarkable genus of bacteria that thrives in extreme, oxygen-poor deep-sea environments through sophisticated biological adaptations. By utilizing specialized “nanocables,” these microorganisms can sense and interact with their surroundings to maintain metabolic activity where most life forms would perish. This guide explores the unique anatomical and physiological traits that allow these organisms to function as essential engineers of the ocean floor.

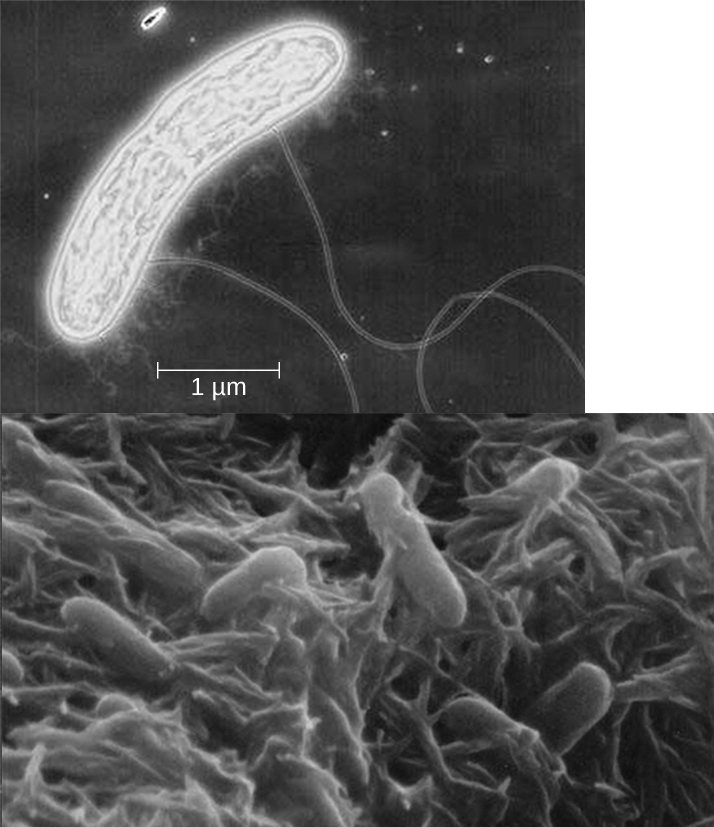

1 μm (micrometer) scale bar: This measurement marker provides a visual reference for the microscopic size of the bacterium, indicating the extremely small scale at which these biological processes occur. It allows researchers to calculate the proportions of the cell and its appendages accurately under high-magnification microscopy.

Bacterial cell body: The main structure of the Shewanella bacterium is typically rod-shaped, housing the essential genetic material and metabolic machinery required for survival. Its complex internal membranes are specifically adapted to function under the high-pressure and low-temperature conditions found on the ocean floor.

Nanocables (conductive appendages): These elongated, hair-like structures extend from the bacterial surface and serve as biological conduits for sensing environmental oxygen levels. They play a critical role in the organism’s unique respiratory strategy by facilitating the transfer of electrons to external acceptors in the environment.

The genus Shewanella represents a fascinating subject in environmental microbiology due to its incredible metabolic versatility. Found primarily in the deep sea and aquatic sediments, these bacteria are renowned for their ability to “breathe” a wide variety of substances. In environments where oxygen is scarce, they adapt by using solid minerals, such as iron or manganese, as terminal electron acceptors in their respiratory chain.

This survival strategy is made possible by a process known as extracellular electron transfer (EET). Unlike most organisms that conduct respiration internally, Shewanella can move electrons across its outer membrane to interact with external surfaces. This physiological trait is not just a biological curiosity; it has significant implications for biotechnological applications, including microbial fuel cells and the bioremediation of contaminated environments.

Key features of Shewanella physiology include:

- High tolerance for low-temperature and high-pressure (piezophilic) environments.

- Production of conductive protein filaments or “nanocables” to reach electron acceptors.

- Flexible respiratory pathways that can switch seamlessly between aerobic and anaerobic modes.

- The ability to form complex biofilms on the seabed for communal survival and resource sharing.

The physical attachment of Shewanella to the seafloor provides a stable anchor in turbulent deep-sea currents. By colonizing these surfaces, the bacteria create a niche where they can efficiently harvest the limited resources available. The integration of their sensory nanocables allows the colony to respond dynamically to fluctuating chemical gradients in the water column, ensuring the organism stays connected to its energy sources.

Anatomy and Physiology of Microbial Bioenergetics

The anatomy of Shewanella is specifically refined for bioenergetics in extreme habitats. One of the most striking features visible in electron micrographs is the presence of conductive appendages. While initially thought to be simple pili, research suggests these “nanocables” are often extensions of the outer membrane and periplasm, containing multi-heme cytochromes. These proteins act as biological wires, allowing the cell to export electrons over distances much larger than the cell body itself.

Physiologically, these nanocables allow the bacterium to bridge the gap between where it is anchored and where usable oxidants might be located. This is essential for maintaining homeostasis in the nutrient-poor deep sea. By sensing trace amounts of oxygen through these filaments, the bacterium can modulate its internal metabolism to maximize energy efficiency. This sensing mechanism is a sophisticated form of chemotaxis that operates over a relatively large spatial scale for a single-celled organism.

Furthermore, the ability of these extremophiles to transfer electrons to external metals has a profound impact on the geochemical cycles of the ocean floor. By reducing insoluble metal oxides into soluble forms, Shewanella helps mobilize nutrients that other members of the deep-sea ecosystem rely on. This role as a primary recycler makes them indispensable to the health of benthic environments and illustrates the interconnectedness of microbial life and global chemistry.

In summary, Shewanella is a master of adaptation, utilizing unique anatomical features like nanocables to thrive in the harsh conditions of the deep sea. Its ability to sense oxygen and conduct extracellular respiration highlights the incredible ingenuity of microbial life. As we continue to study these organisms, we not only uncover the secrets of deep-sea ecology but also pave the way for innovative energy and environmental technologies that mimic these natural conductive systems.