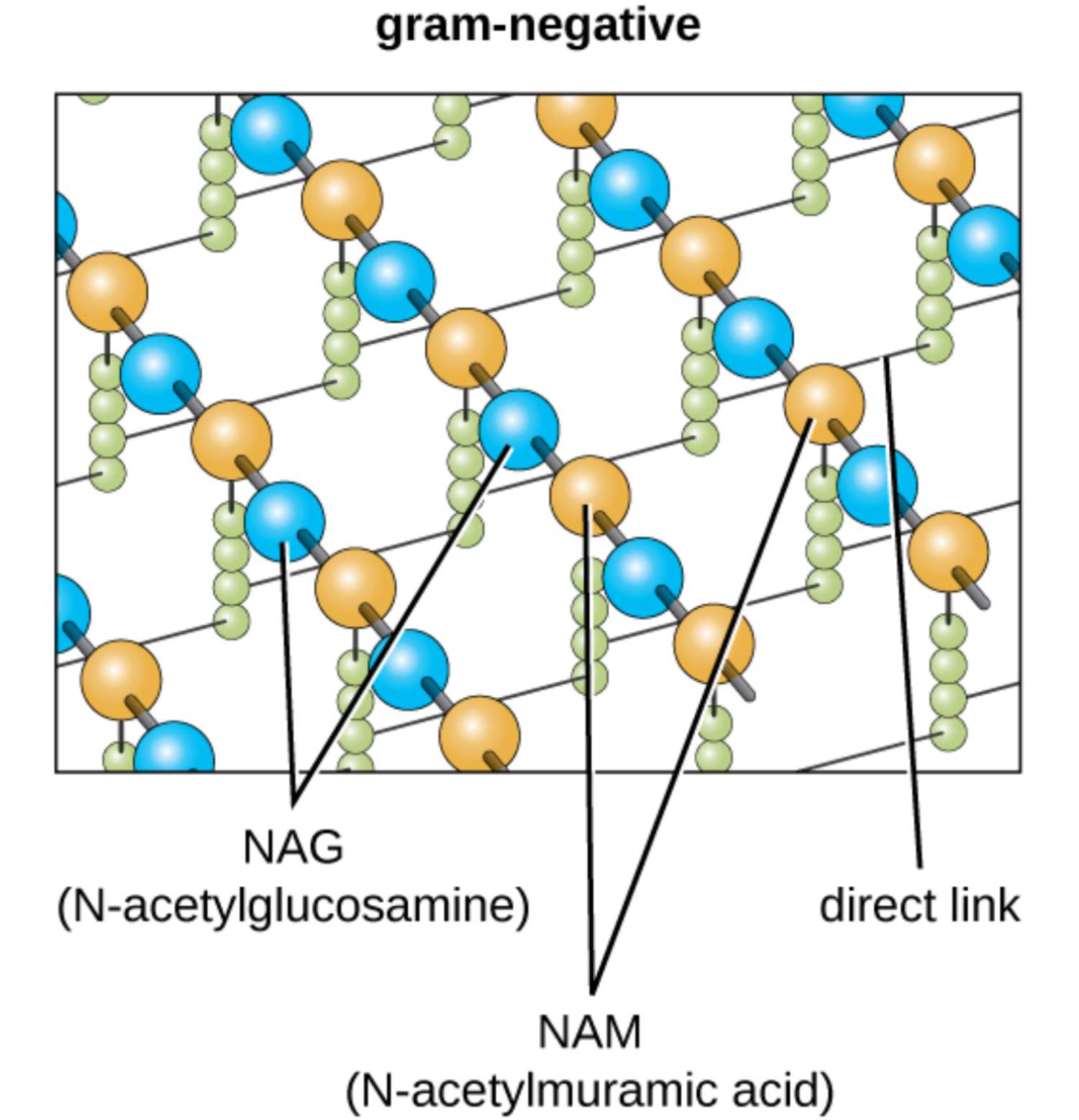

The Gram-negative bacterial cell wall is a sophisticated multi-layered structure designed for survival and protection. Central to this architecture is a thin yet resilient layer of peptidoglycan, characterized by a unique arrangement of alternating sugar subunits and direct peptide cross-links that provide essential structural stability. Understanding these molecular details is crucial for grasping how Gram-negative pathogens maintain their integrity and resist various medical interventions.

gram-negative: This refers to a category of bacteria that possess a thin peptidoglycan layer situated between an inner cytoplasmic membrane and an outer membrane. These organisms do not retain the primary crystal violet stain during a Gram stain test, appearing red or pink under a microscope.

NAG (N-acetylglucosamine): One of the two primary amino sugars that constitute the carbohydrate backbone of the bacterial cell wall. It alternates with NAM to form long glycan strands that provide the longitudinal strength required to support the cell’s shape.

NAM (N-acetylmuramic acid): This sugar molecule is the second repeating unit of the glycan polymer and serves as the attachment point for peptide side chains. It is chemically distinct from NAG due to the presence of a lactic acid ether, which allows for the covalent bonding of amino acids.

direct link: In Gram-negative bacteria, this is a covalent bond that connects the third amino acid of one peptide chain directly to the fourth amino acid of an adjacent chain. This compact cross-linking method provides a tight lattice structure that is more streamlined than the interbridges found in other bacterial types.

The Functional Role of Peptidoglycan in Microbial Life

The peptidoglycan layer in Gram-negative bacteria, although thinner than that of their Gram-positive counterparts, plays a pivotal role in maintaining cellular shape and protecting the organism from mechanical stress. It consists of a complex polymer of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like scaffold around the plasma membrane. This scaffold is essential for withstanding the high internal turgor pressure typical of microbial life, preventing the cell from bursting in hypotonic environments.

Functionally, this layer exists within the periplasmic space, a compartment between the inner and outer membranes. This positioning allows the peptidoglycan to act as a structural mediator, providing the necessary rigidity while still being part of a larger, more fluid envelope system. The direct links between glycan chains ensure that the lattice remains stable even with a reduced volume of material compared to other bacterial species.

Key characteristics of the Gram-negative peptidoglycan structure include:

- The presence of alternating NAG and NAM subunits joined by β-(1,4) glycosidic bonds.

- Short peptide side chains attached to the NAM units.

- Direct cross-linking between peptide chains, often involving meso-diaminopimelic acid (m-DAP).

- A single-layer or few-layered arrangement that maximizes efficiency without sacrificing integrity.

From a medical standpoint, this structure is a primary target for many antibacterial agents. However, the presence of the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria adds a layer of complexity, often shielding the peptidoglycan from large or hydrophilic molecules. This dual-membrane system is a major factor in the clinical challenge of treating infections caused by Gram-negative pathogens.

Cellular Physiology and Enzyme Dynamics

The biological success of Gram-negative bacteria is largely attributed to the synergy between the peptidoglycan layer and the surrounding membranes. The peptidoglycan acts as the mechanical “skeleton,” while the outer membrane functions as a chemical “sieve.” Because the peptidoglycan layer is relatively thin (usually only 1–3 layers), it is highly dynamic, allowing for rapid remodeling during cell growth and division.

The biosynthesis of this layer involves a series of complex enzymatic reactions. Enzymes known as autolysins carefully break existing bonds to allow for the insertion of new NAG and NAM subunits, while transpeptidases (also known as penicillin-binding proteins) catalyze the formation of the direct links. If this balance is disrupted, the cell wall weakens, leading to eventual rupture and death of the bacterium.

Clinical Implications and Antibiotic Resistance

In clinical practice, the structural differences in peptidoglycan help explain why certain antibiotics are more effective against specific bacteria. For example, while beta-lactams target the cross-linking process, their access to the peptidoglycan in Gram-negative bacteria is regulated by porins in the outer membrane. Many Gram-negative species have developed resistance by narrowing these porin channels or by producing enzymes like beta-lactamases that reside in the periplasm and destroy the drug before it can reach the cell wall.

Furthermore, fragments of peptidoglycan released during bacterial growth or death are recognized by the human immune system as “pathogen-associated molecular patterns” (PAMPs). These fragments bind to receptors such as NOD1 and NOD2 in host cells, triggering an inflammatory cascade. This response is vital for clearing infections but can also lead to the detrimental tissue damage associated with chronic inflammatory conditions or septic shock.

The intricate molecular design of Gram-negative peptidoglycan highlights the incredible adaptability of microbial life. By utilizing a thin but highly cross-linked lattice of NAG and NAM subunits, these bacteria achieve a balance of strength and flexibility. Continued research into these structural components is essential for the development of novel therapeutic strategies that can overcome the formidable defenses of Gram-negative pathogens and improve patient outcomes in infectious disease management.