The Gram-positive bacterial cell wall is a robust and sophisticated biological barrier that provides essential structural support and protection. Characterized primarily by its extensive, multi-layered peptidoglycan meshwork, this structure is the defining feature used to classify a vast array of pathogens and beneficial microbes in medical microbiology. Understanding the molecular layout of these components is fundamental to diagnosing infectious diseases and developing targeted antimicrobial therapies that disrupt cellular integrity.

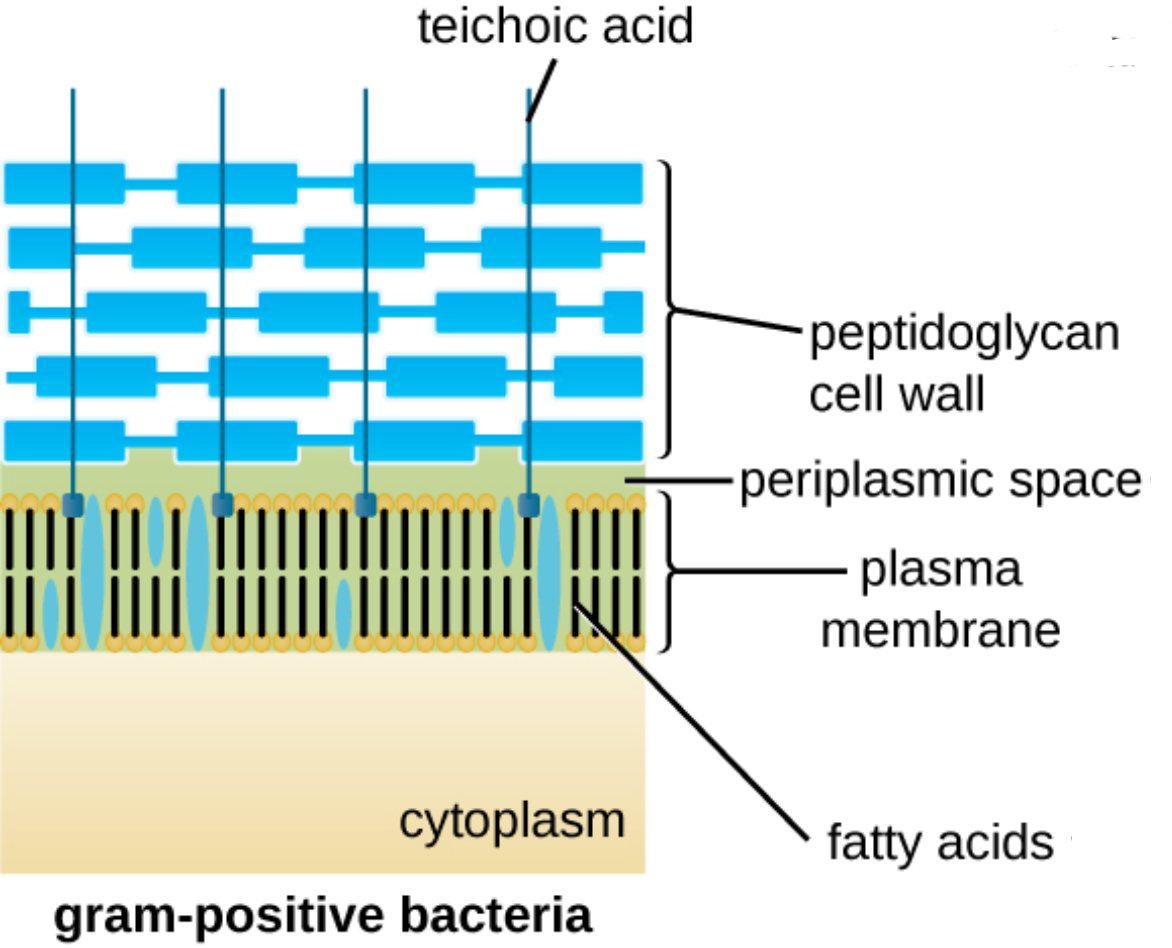

teichoic acid: These are anionic polymers that are either covalently linked to the peptidoglycan or anchored to the plasma membrane. They play a vital role in regulating cell division, maintaining wall rigidity, and serving as primary attachment sites for host cells during the initial stages of infection.

peptidoglycan cell wall: Often referred to as murein, this is a thick, porous scaffold composed of alternating sugar subunits cross-linked by short peptide chains. It functions as a structural exoskeleton, providing the necessary tensile strength to prevent the bacterium from bursting due to high internal pressure.

periplasmic space: This is the concentrated, gel-like region situated between the inner cytoplasmic membrane and the thick outer peptidoglycan layer. It houses a variety of enzymes and transport proteins that facilitate nutrient acquisition and the initial stages of metabolic processing.

plasma membrane: This selectively permeable phospholipid bilayer serves as the primary interface between the cell’s internal environment and the external world. It is the site of critical physiological functions, including the regulation of molecular transport and the production of ATP through the electron transport chain.

fatty acids: These long hydrocarbon chains constitute the hydrophobic core of the phospholipids within the plasma membrane. The specific saturation and length of these fatty acids determine the membrane’s fluidity and its effectiveness as a barrier against toxic substances.

cytoplasm: This is the internal aqueous environment where the bacterial genome, ribosomes, and various metabolic intermediates are suspended. It is the central hub for most biochemical activities, including DNA replication, transcription, and the synthesis of proteins necessary for survival.

The Physiological Significance of the Gram-Positive Envelope

In the field of clinical microbiology, the distinction between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria is a cornerstone of diagnosis. Gram-positive organisms are identified by their ability to retain the crystal violet stain, a phenomenon directly attributed to the density of their peptidoglycan layer. This layer can consist of up to 40 layers of cross-linked polymers, making it significantly thicker and more physically resilient than the walls found in other bacterial classes.

The cell wall is not merely a passive container; it is a dynamic organelle involved in sensing and responding to the environment. Because the internal environment of a bacterium is typically hypertonic compared to the outside world, water constantly attempts to rush into the cell. The peptidoglycan structure provides the mechanical resistance required to prevent osmotic lysis, which would otherwise lead to immediate cell death.

Core characteristics of the Gram-positive cell wall include:

- A thick peptidoglycan layer ranging from 20 to 80 nanometers in depth.

- The presence of teichoic acids which contribute to a negative surface charge.

- The absence of an outer lipid membrane, allowing direct access to the peptidoglycan for certain molecules.

- High sensitivity to enzymes such as lysozyme, which cleaves the sugar backbone of the wall.

This anatomical configuration makes Gram-positive bacteria particularly susceptible to certain classes of medication. Because human cells do not possess peptidoglycan, it serves as an ideal target for selective toxicity. Drugs can effectively neutralize the pathogen without damaging the host’s own tissues by specifically interfering with the assembly of this unique microbial “armor.”

Pathogenicity and Antimicrobial Targets

From a clinical perspective, the components of the Gram-positive wall are major virulence factors that influence how a disease progresses. For instance, the teichoic acids extending from the surface can trigger inflammatory responses in the host or help the bacteria evade the immune system by masking other surface antigens. This molecular complexity allows bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pneumoniae to colonize human tissues and cause systemic infections.

The synthesis of peptidoglycan is the primary target for beta-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillin and amoxicillin. These drugs function by binding to transpeptidase enzymes, effectively preventing the cross-linking of peptide chains during cell wall construction. When these bridges fail to form, the wall becomes mechanically unstable, leading to the collapse of the cell under its own internal pressure.

Cellular Homeostasis and Defense

The plasma membrane beneath the thick cell wall is equally important for maintaining bacterial pathogenesis and survival. While the wall provides physical strength, the membrane provides chemical control. It acts as a gatekeeper, utilizing specialized transport proteins to bring in essential nutrients like glucose and ions while simultaneously pumping out waste products or invading antibiotics through efflux pumps.

In summary, the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall is a marvel of biological engineering that balances rigidity with functionality. Its thick peptidoglycan layer and embedded teichoic acids create a formidable barrier that protects the delicate internal cytoplasm while facilitating interaction with the host. By studying these structures, medical science continues to refine the tools used to combat infections, ensuring that therapies remain effective against even the most resilient bacterial threats.