Explore the fascinating anatomy of the amphibian heart, a crucial adaptation for animals transitioning between aquatic and terrestrial environments. This article delves into the unique three-chambered structure, highlighting how it efficiently manages both oxygenated and deoxygenated blood flow. Understand the intricate system that allows amphibians to maintain their metabolic needs while utilizing both pulmonary and cutaneous respiration.

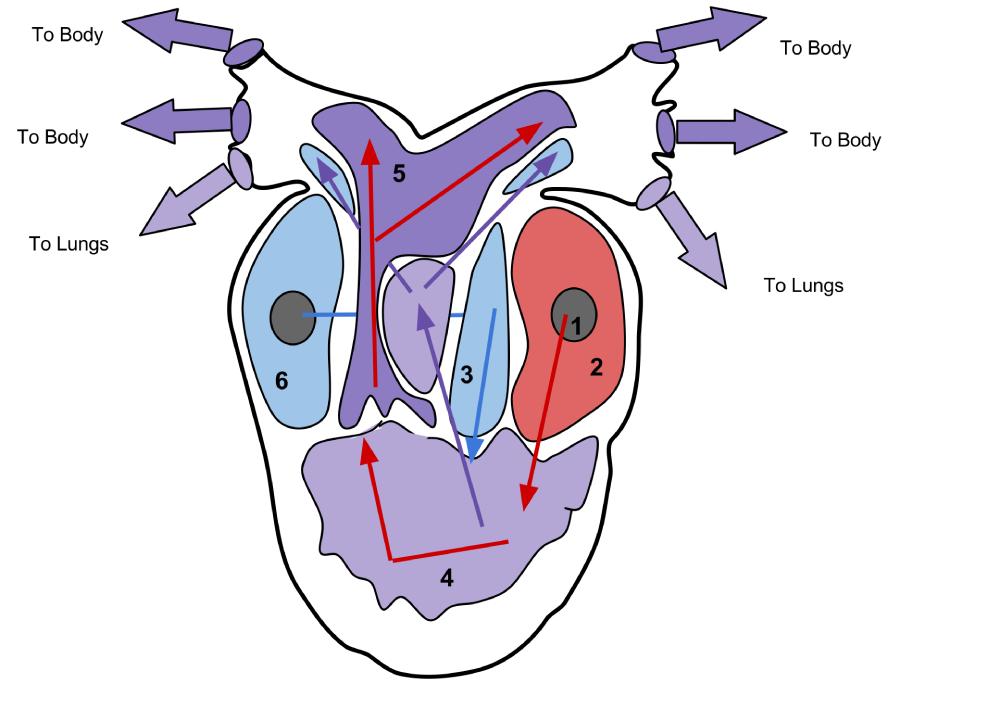

Pulmonary Vein (1): This vessel carries oxygenated blood from the lungs and skin back to the heart. In amphibians, both the lungs and the highly vascularized skin contribute significantly to gas exchange, making the pulmonary vein a critical conduit for oxygen-rich blood.

Left Atrium (2): The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the pulmonary vein. It then contracts to pump this oxygenated blood into the single ventricle, initiating the systemic circulation.

Right Atrium (3): The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the systemic circulation, via the sinus venosus. From here, it contracts to send the deoxygenated blood into the ventricle, destined for the lungs and skin for re-oxygenation.

Ventricle (4): The ventricle is the single, muscular pumping chamber of the amphibian heart. It receives both oxygenated blood from the left atrium and deoxygenated blood from the right atrium, and despite being a single chamber, it employs mechanisms to minimize mixing and preferentially shunt blood to either the pulmonary or systemic circuits.

Conus arteriosus (5): This is a muscular outflow tract that extends from the ventricle, also known as the bulbus cordis or truncus arteriosus in some contexts. It contains a spiral valve that helps to separate the deoxygenated blood destined for the pulmonary arteries (to the lungs and skin) from the oxygenated blood destined for the systemic arteries (to the body).

Sinus venosus (6): The sinus venosus is a thin-walled sac that receives deoxygenated blood from the body (via the vena cavae) before it enters the right atrium. It acts as a collecting chamber and plays a role in initiating the heartbeat by functioning as the primary pacemaker in amphibians.

The amphibian heart is a remarkable evolutionary adaptation, representing a transitional stage between the simpler two-chambered heart of fish and the more complex four-chambered hearts of birds and mammals. Its unique structure, typically featuring three chambers—two atria and a single ventricle—allows amphibians to efficiently manage a dual circulatory system that supports both aquatic and terrestrial respiration. This adaptability is crucial for animals like frogs, toads, and salamanders, which often rely on a combination of gills (in larval stages), lungs, and cutaneous (skin) respiration throughout their life cycle.

A key challenge for any circulatory system with a single ventricle is minimizing the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. Despite having only one ventricle, the amphibian heart employs several anatomical and physiological mechanisms to achieve a functional separation. These include the asynchronous contraction of the atria, specialized folds or trabeculae within the ventricle, and the presence of a spiral valve within the conus arteriosus. This partial separation ensures that the body receives relatively oxygen-rich blood, while deoxygenated blood is primarily directed towards the respiratory surfaces for gas exchange.

The efficiency of this three-chambered heart, coupled with the ability to shunt blood, is vital for an amphibian’s survival. For instance, when diving underwater, an amphibian can reduce blood flow to the lungs and increase cutaneous respiration, bypassing the pulmonary circuit. Conversely, when on land, the pulmonary circuit becomes more active. This flexibility in blood flow regulation allows amphibians to optimize oxygen uptake depending on their environmental conditions and activity levels, showcasing the effectiveness of this seemingly less complex cardiac design.

Key features of the amphibian heart include:

- Three chambers: Two atria and one ventricle.

- Dual circulation: Systemic and pulmonary/cutaneous circuits.

- Minimizing blood mixing: Achieved by ventricular trabeculae and conus arteriosus spiral valve.

- Adaptation for respiration: Efficiently supplies blood to lungs and skin.

- Sinus venosus: Primary pacemaker and blood collection.

In conclusion, the amphibian heart, with its distinctive three-chambered design and sophisticated mechanisms for regulating blood flow, is a critical adaptation that underpins the physiological success of amphibians. The coordinated efforts of the pulmonary vein, atria, single ventricle, conus arteriosus, and sinus venosus ensure an efficient dual circulation system capable of supporting both aquatic and terrestrial lifestyles. This remarkable cardiovascular system highlights the evolutionary ingenuity that enabled vertebrates to transition from water to land, making the amphibian heart a fascinating subject in comparative anatomy and physiology.