The cytoskeleton is an intricate and dynamic network of protein filaments that serves as the architectural scaffolding for eukaryotic cells, providing structural integrity and facilitating vital biological processes. By coordinating the spatial organization of organelles and enabling cellular motility, this system ensures that cells can maintain their shape while adapting to environmental changes. This guide explores the distinct components of the cytoskeleton—microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments—and their essential roles in human physiology.

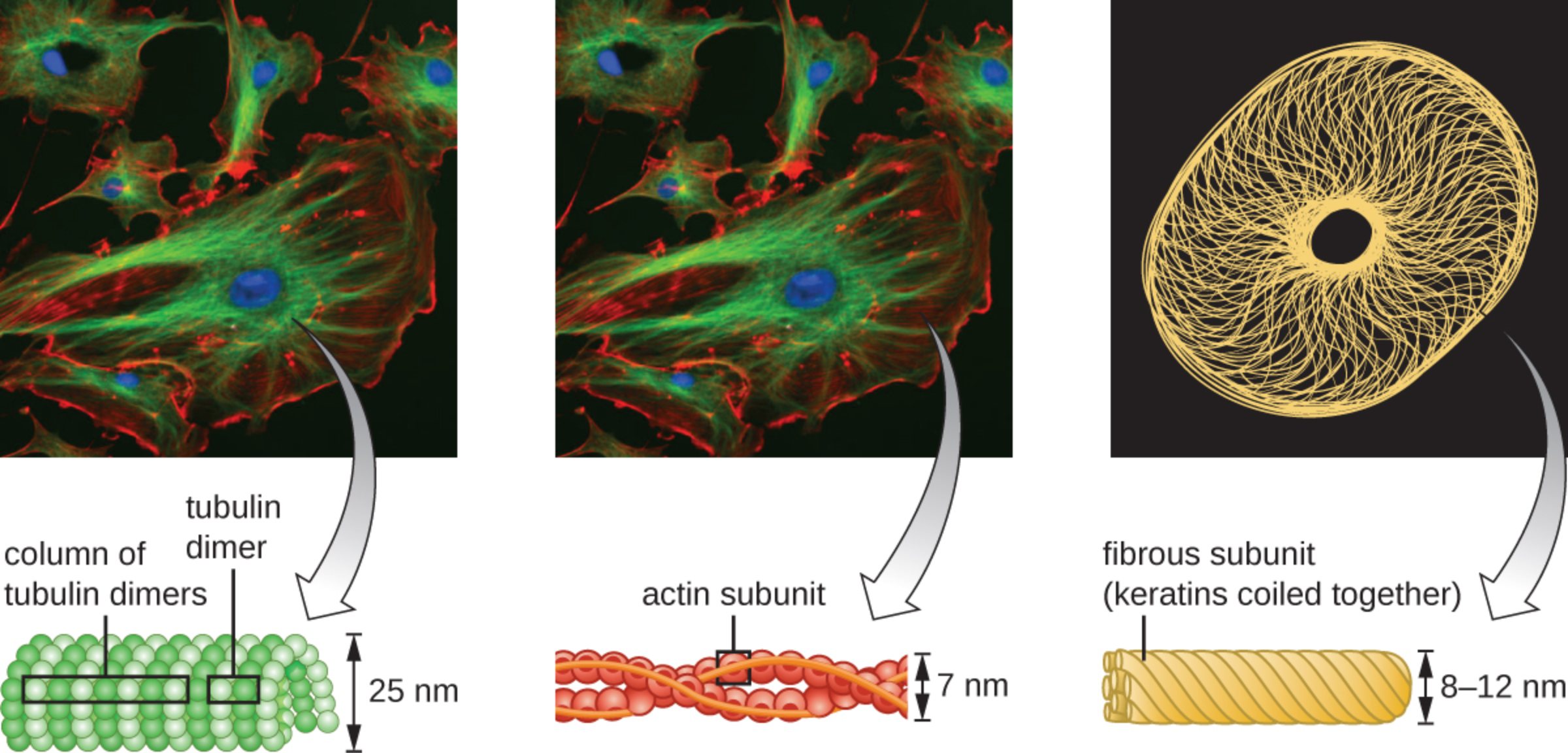

tubulin dimer: This is the fundamental building block of microtubules, consisting of alpha-tubulin and beta-tubulin proteins joined together. These dimers polymerize in a head-to-tail fashion to form protofilaments that eventually assemble into hollow tubes.

column of tubulin dimers: This label refers to a protofilament, which is a longitudinal row of polymerized tubulin dimers. Typically, thirteen of these columns arrange themselves in a circular pattern to create the characteristic cylindrical shape of a microtubule.

25 nm: This measurement indicates the external diameter of a microtubule, identifying it as the thickest of the three cytoskeletal filaments. This substantial size provides the rigidity necessary for maintaining cell shape and acting as tracks for motor proteins.

actin subunit: These are individual globular proteins, known as G-actin, that assemble into long, twisted chains called filamentous actin. These subunits are essential for cellular processes requiring force and movement, such as muscle contraction and cytokinesis.

7 nm: This dimension represents the diameter of a microfilament, characterizing it as the thinnest component of the cytoskeleton. Despite their small size, they are incredibly versatile and allow the cell to change its shape rapidly in response to external stimuli.

fibrous subunit (keratins coiled together): This structure is composed of several fibrous proteins, such as keratin, wound together like a rope to provide high tensile strength. These subunits form intermediate filaments that help cells withstand mechanical stress and securely anchor the nucleus in place.

8–12 nm: This range describes the diameter of intermediate filaments, which falls between that of microfilaments and microtubules. This specific thickness is optimized for providing permanent structural support and reinforcing the cell’s internal framework against physical tension.

The Dynamic Architecture of the Cell

The cytoskeleton is far more than a static skeleton; it is a highly regulated and constantly shifting system of protein fibers found throughout the cytoplasm. It allows cells to perform complex tasks such as moving through tissues, transporting materials internally, and physically separating during replication. In the provided fluorescence microscopy images, we see these components highlighted in vivid detail: microtubules appear green, actin microfilaments are red, the nucleus is blue, and keratin intermediate filaments are yellow.

Each type of filament has a unique protein composition and mechanical property suited for specific cellular needs. While some provide the “railroad tracks” for moving vesicles, others act as “cables” to pull the cell forward or “anchors” to keep organelles from drifting. This collaborative effort ensures that the internal environment remains organized even as the cell undergoes significant morphological changes.

The primary structural components of this network include:

- Microtubules: Thick, hollow tubes involved in organelle movement and chromosomal separation.

- Microfilaments: Thin, flexible strands that support cell shape and enable movement.

- Intermediate Filaments: Tough, fibrous strands that provide mechanical strength and durability.

In clinical medicine, the cytoskeleton is a major target for various therapies. For instance, certain chemotherapy drugs work by disrupting microtubule assembly, thereby halting the uncontrolled cell division seen in malignant tumors. Understanding the nuances of these protein networks provides a window into both healthy cellular function and the mechanisms of disease.

Microtubules: The Highway for Intracellular Transport

Microtubules are the largest components of the cytoskeleton and are characterized by their remarkable stiffness. They originate from the centrosome, a microtubule-organizing center located near the nucleus. Beyond providing structural support, they function as a primary system for intracellular transport, where motor proteins like kinesin and dynein “walk” along the tubulin columns to deliver cargo to various parts of the cell.

Physiologically, microtubules are also the structural core of cilia and flagella. These hair-like extensions are crucial in the human body, such as the cilia in the respiratory tract that sweep mucus and debris out of the lungs. During mitosis, microtubules form the spindle apparatus, which is responsible for accurately segregating chromosomes into daughter cells, ensuring genetic stability across generations of cells.

Microfilaments and Intermediate Filaments: Movement and Strength

Microfilaments, composed primarily of actin, are concentrated just beneath the plasma membrane in a region called the cortex. They are responsible for the “crawling” motion of cells, such as white blood cells migrating toward a site of infection. By rapidly polymerizing and depolymerizing, actin filaments can push the cell membrane forward, creating extensions known as pseudopodia. This flexibility is what allows cells to change shape, squeeze through narrow capillaries, and perform endocytosis.

Intermediate filaments, such as those made of keratin, provide the most permanent structural reinforcement. Unlike the highly dynamic microtubules and microfilaments, intermediate filaments are more stable and do not frequently disassemble. They are particularly abundant in skin cells, where they form a network that prevents the cell layers from tearing under physical pressure. By connecting to specialized junctions called desmosomes, intermediate filaments link neighboring cells together, creating a cohesive and resilient tissue structure.

The cytoskeleton represents a masterpiece of biological engineering, balancing the need for rigid stability with the requirement for fluid movement. It is the invisible hand that guides every heartbeat, every step, and every immune response. As we continue to study these microscopic fibers, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complex interactions that sustain life at the most fundamental level.