Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as Group A Streptococcus (GAS), is a significant human pathogen responsible for a wide spectrum of diseases, ranging from mild pharyngitis to life-threatening invasive infections. This article explores its unique chain-like morphology under Gram stain and its characteristic hemolytic activity on blood agar, providing essential insights for clinical diagnosis and effective patient management.

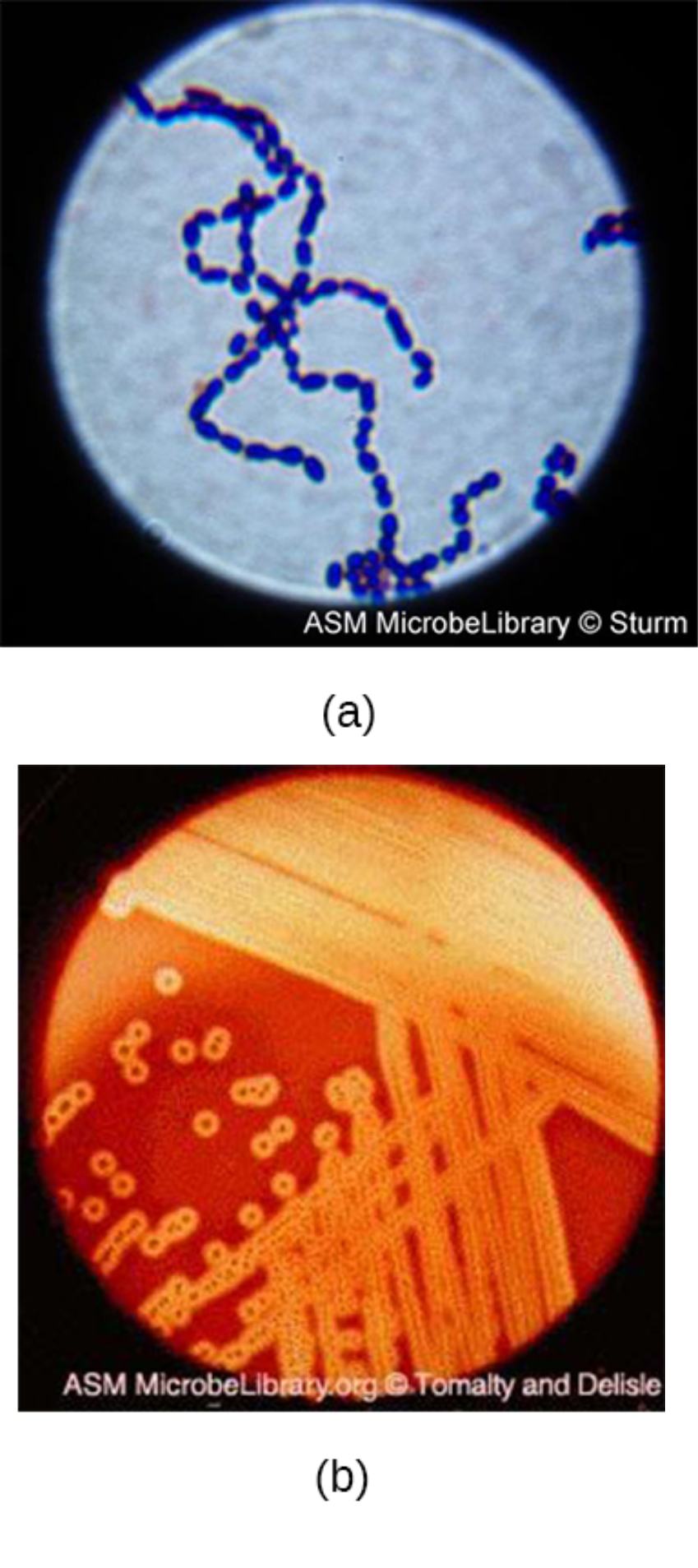

(a): This image displays a Gram-stained microscopic specimen showing the classic arrangement of Streptococcus pyogenes in long, winding chains. This specific formation occurs because the individual spherical cocci divide along a single plane and remain attached to one another following cellular division.

(b): This panel illustrates the growth of the bacteria on a sheep blood agar plate, showcasing a distinct halo of clearing around the bacterial colonies. This complete destruction of red blood cells is known as beta-hemolysis, a hallmark laboratory feature used by microbiologists to differentiate virulent streptococci from less harmful species.

Streptococcus pyogenes is a ubiquitous Gram-positive bacterium that primarily colonizes the human respiratory tract and skin. While it can exist as a transient commensal in the microbiome of healthy individuals, it is most recognized for its formidable array of virulence factors. These specialized tools allow the organism to evade the host immune system, adhere to mucosal surfaces, and trigger intense inflammatory responses.

In the clinical setting, diagnostic identification is paramount for preventing the spread of infection and avoiding severe secondary complications. Laboratory technicians utilize the microbiological signatures shown in the provided images—specifically the chain-like morphology and the hemolytic clearing on agar—to confirm the presence of GAS. Furthermore, S. pyogenes is typically sensitive to the antibiotic bacitracin, which serves as an additional diagnostic test to distinguish it from other beta-hemolytic streptococci.

The clinical manifestations of Group A Streptococcal infections are diverse and include:

- Streptococcal pharyngitis (commonly known as “Strep throat”)

- Impetigo, erysipelas, and cellulitis of the skin

- Scarlet fever, characterized by a distinctive “strawberry tongue” and rash

- Severe invasive conditions such as streptococcal toxic shock syndrome

Microbiological Characteristics and Virulence Factors

The pathogenicity of S. pyogenes is driven by its complex cellular structure and secreted toxins. One of the most critical components is the M protein, a filamentous structure on the cell surface that prevents the host’s complement system from labeling the bacteria for destruction by white blood cells. This protein is also implicated in molecular mimicry, where the immune system mistakenly attacks host tissues, leading to post-infectious sequelae such as rheumatic fever.

The “halos of clearing” seen in laboratory cultures are caused by the release of streptolysins, specifically streptolysin O and streptolysin S. These potent cytolysins do not just destroy red blood cells in a petri dish; they also target and kill leukocytes in the human body, effectively disarming the local immune response. Additionally, certain strains produce erythrogenic toxins, which are responsible for the systemic rash seen in patients suffering from scarlet fever.

Clinical Impact: From Pharyngitis to Necrotizing Fasciitis

While most GAS infections present as manageable respiratory or skin ailments, the bacterium can occasionally manifest as necrotizing fasciitis. Often referred to by the media as “flesh-eating disease,” this condition involves the rapid destruction of deep muscle fascia and skin. The bacteria spread with alarming speed, requiring a combination of aggressive surgical debridement and high-dose intravenous antibiotics to save the patient’s life and limbs.

Beyond acute infections, S. pyogenes is notorious for causing immune-mediated complications. Acute rheumatic fever remains a major public health concern in many parts of the world, where untreated throat infections lead to inflammatory damage to the heart valves, joints, and nervous system. Similarly, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis can occur following either skin or throat infections, resulting in acute kidney inflammation and potential renal impairment.

The distinct morphology and biochemical behavior of Streptococcus pyogenes continue to serve as the foundation for modern infectious disease diagnostics. By recognizing the transition from a simple sore throat to a systemic or immune-mediated illness, healthcare providers can intervene early with penicillin or other effective antibiotics. Ongoing vigilance in identifying these microscopic chains and hemolytic patterns remains essential for protecting public health and reducing the global burden of streptococcal disease.